On April 9th, 2021, La Soufrière Volcano, on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, began to erupt for the first time in 42 years. These explosive eruptions left the conservation community gravely concerned about impacts to the island’s wildlife and vegetation. Using funds raised through our volcano recovery campaign, BirdsCaribbean, the Saint Vincent Department of Forestry, and Antioch University were able to begin assessing the effects. Here, we report on field work from our successful two-week pilot season surveying for the endemic Whistling Warbler and other forest species in May of 2022. Field Assistant Kaitlyn Okrusch shares her experiences—read on!

There is something indescribable about witnessing a creature that so few have laid eyes on. Not because it makes you lucky over others. Rather, this creature, this other living thing, has somehow managed to stay hidden from our pervasive (and distinctly) human nature. This thought crossed my mind several times as I glimpsed a view of the Whistling Warbler—a really rare bird found only on one island and restricted to mountainous forest habitat. As I gazed up at this endemic gem, I imagined its secretive life. With its stocky body, bold white eye-ring, cocked tail, and tilted head, it looked back down at me, just as curious.

There is something indescribable about witnessing a creature that so few have laid eyes on. Not because it makes you lucky over others. Rather, this creature, this other living thing, has somehow managed to stay hidden from our pervasive (and distinctly) human nature. This thought crossed my mind several times as I glimpsed a view of the Whistling Warbler—a really rare bird found only on one island and restricted to mountainous forest habitat. As I gazed up at this endemic gem, I imagined its secretive life. With its stocky body, bold white eye-ring, cocked tail, and tilted head, it looked back down at me, just as curious.

When Mike Akresh, a conservation biology professor at Antioch University New England, asked if I wanted to assist a pilot study for the Whistling Warbler on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, I paused. “The Whistling Warbler?” I thought, “Saint Vincent?” I had never heard of the bird nor the island. Now, I don’t know how I could ever forget either.

Saint Vincent is located in the southern Lesser Antilles, and has a kite tail of 32 smaller islands and cays (the Grenadines) dotting southward. Its indigenous name is ‘Hairouna,’ which translates to the Land of the Blessed. The people, the culture, and the biodiversity are truly remarkable—blessed indeed. In addition to the warbler, the islands are home to the national bird, the colorful and endemic Saint Vincent Parrot, and host to six other bird species that are found only in the Lesser Antilles.

The rumblings, then eruptions, that ignited our work

At the northernmost point of this island lives the active volcano, La Soufrière, which last erupted in 1979. In December of 2020, this powerful mountain showed signs of life with effusive eruptions and growth of the lava dome for several months. On April 9th 2021, explosive eruptions began that sent plumes of ash as high as 16 kilometers. In addition, pyroclastic flows and lahars (very fast-moving, dense mudflows or debris flows consisting of pyroclastic material, rocky debris, ash and water) caused considerable damage along river valleys and gullies.

Multiple eruptions in April damaged trees and blanketed the forests and towns in thick layers of gray ash, leaving many parts of the island barren for months. Upwards of 20,000 people were evacuated in the Red and Orange Zones (northern half of the island), and, thanks to this decision, there was no loss of life. Remarkably, the 2021 eruption of La Soufriere is the largest to occur in the entire Caribbean of at least the last 250 years.

There was grave concern for the welfare of the Saint Vincent Parrot, Whistling Warbler, and other wildlife. BirdsCaribbean launched a fundraising campaign and our community stepped up to provide funding and supplies for volcano recovery efforts, both short and longer-term. This natural disaster was destructive for both the people and the land; the impacts are still being seen and felt today. But, out of this catastrophe arose an opportunity to assess the status of Saint Vincent’s iconic birds and to plan for their conservation moving forward.

The eruption of La Soufrière called attention to the urgent need for collaboration and research efforts regarding biodiversity conservation on Saint Vincent. With such limited baseline knowledge pertaining to most of the forest birds on the island, locals worried that some species (like the Whistling Warbler and the Saint Vincent Parrot) might disappear. No one was sure how these eruptions had impacted their populations.

This opened the door for concerted efforts between the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Department of Forestry (SVGF), BirdsCaribbean, and Antioch University, to complete a pilot season surveying for the elusive and endangered Whistling Warbler and other endemic landbirds. SVGF and researchers from Florida International University (led by Dr. Cristina Gomes) were already in the process of specifically re-surveying the Saint Vincent Parrot population, so our surveys focused on other landbirds (stay tuned for a blog post on this work!).

Touching down for the “oreo” bird

My eyes grew wide as the plane touched down and I stepped out into the humid, salty air. Lisa Sorenson (the executive director of BirdsCaribbean) had been down here for the previous few days with her husband, Mike Sorenson, and colleagues Jeff Gerbracht (Cornell Lab of Ornithology and long time BirdsCaribbean member) and Mike Akresh. They had been scouting out potential locations for our surveys of the warbler using the PROALAS point count protocol with SVGF and specifically SVGF Wildlife Unit Head, Glenroy Gaymes.

Lisa and Mike A. picked me up from the Argyle International Airport in a silver Suzuki jeep—driver’s side on the right, drive on the left. I hopped in the car and we zipped off into the narrow (and steep!) hillside roads of Arnos Vale—a small community north of the capital of Kingstown. Lisa had been down here before. She drove us around like a local: confident and happy, despite the crazy traffic and winding roads! I rolled down the window and the sun brushed my face. Our first stop before our home base was a local fruit stand, well equipped with juicy mangoes, soursop, plantains, pineapple, and grapefruits. Island life and fresh fruits—nothing quite compares!

As Lisa and Mike picked out the various ripe fruits they wanted, Lisa didn’t miss an opportunity to ask the stand tenders if they had ever heard of or seen the Whistling Warbler. She took out her phone, pulled up the Merlin Bird ID app, and displayed some of the few captured sounds and photographs of this bird. She held it up for them to see. “Ahhhh, yes, we’ve heard that before!” the man said, after listening to the song. A smile crept onto his face. The unmistakable call of this bird, as I would come to observe, has been ingrained into the minds of many locals—without them even knowing who was making it. “We hear that many times when we are in the forest,” the woman said.

The song of the Whistling Warbler is a crescendo trill of loudly whistled notes.

Many locals (and non locals) are unaware that the Whistling Warbler is endemic to Saint Vincent. On the other hand, many are aware that the beautiful and iconic Saint Vincent Parrot is endemic. Endemic species are naturally more vulnerable to extinction due to their specific nature: their limited distribution leaves them particularly vulnerable to threats like habitat destruction, climate change, invasive predators, or overhunting. On top of those reasons—as noted above—their survival may be even more perilous after a devastating volcanic eruption. It is well known that often the large, flamboyantly colored birds captivate, motivate, and receive more funding when it comes to conservation. Sometimes the smaller, less colorful birds quite literally get lost in the shadows. Because of a lack of research and funding, there are large knowledge gaps pertaining to the Whistling Warbler’s ecology and population status.

There are only two scientific papers out there (one unpublished) that contain what little we know about the Whistling Warbler. Consequently, you often see “no information” listed under the various tabs if you search for this species on the Birds of the World website. What is its breeding biology? Do we actually understand the plumage variations between sexes and ages? What about habitat preference and home range size? Diet? Perceived versus actual threats regarding its conservation?

Furthermore, this warbler is interesting because it is also monotypic. It’s in a genus all of its own, and there are no subspecies. This makes the warbler especially unique, and it may be susceptible to changes that we could be causing (and accelerating).

Unfortunately, as with many endemic birds throughout the Caribbean, the lack of capacity, funding, and previous interest has limited our ability to answer these research questions and better conserve these endemic species. Few have had the time (or the funding) to put into fielding these research questions. These are some of the motivations to try and research—to understand—this unique bird and its ecology. We hope to try and figure out the status of this endangered warbler and build local capacity to monitor the warbler and other birds.

Hiking, Birding, and Counting, Oh My!

Most birders acknowledge that in order to see a bird, you need to be a bird. This means getting up at unpleasantly early times, 4 am for example. But, more often than not, it is well-worth the short night of sleep, driving in the dark, and arduous hiking, to watch and hear the lush green forest wake up. On our first field morning, we headed to a trail called Montréal, a steep ascent up the mountain, that became Tiberoux trail, once you reached the saddle and hiked down the other side. This was an area that SVGF staff had both seen and heard our small, feathered friend before.

Utilizing local and SVGF staff knowledge was a crucial aspect of our surveying strategy. Our team visited sites and hiking trails where the warbler was known to be seen or heard in the past. We then conducted point counts within these areas to collect data on the presence/absence of the warbler and other forest species. Glenroy (AKA “Pewee”) has a wealth of knowledge about Saint Vincent’s forests and wildlife. His deep connection with the land comes from inherent connection and diligent observation: being a part of and not apart from the land. He has been walking these trails for 30+ years, patiently learning. Now, he was going to try and teach us about one of his favorite birds.

At first glance, the Whistling Warbler seems nearly impossible to study, partly due to its elusive nature, and partly due to its apparent habitat preference. This bird is found in dense, mountainous forests on extreme slopes of ridges and slippery ravines. This, as you can imagine, makes it difficult to track the bird, let alone nest search. One wrong step, and you can be sent flying down the mountain.

Luckily, with Glenroy’s knowledge and our protocol incorporating a playback song of this species, we were given glimpses here and there as the warbler flitted through the dense, dark, mid-canopy. Digging our heels into the steep sides of the trail, we would all anxiously listen for and await our prized subject. You could feel the tension rising as each of us swiveled our heads back and forth, looking for any sign of movement. “I see it, I see it, right there!” one of us would whisper—the others getting our binoculars ready.

For this two week pilot season, we wanted to rely on local knowledge to understand where to place our PROALAS point counts. PROALAS is a protocol used throughout Central America, and is now beginning to be implemented with BirdsCaribbean’s new Caribbean Landbird Monitoring Project. The protocol includes a standardized set of survey methods for monitoring birds, specially designed for tropical habitats. For our study, we would stop and do a 10-minute point count, noting every single bird that we see and/or hear every 200 meters along a designated trail. This methodology is a quick and systematic way to get an understanding of the landbirds in an area.

Additionally, we collected vegetation and habitat data which can then be used to understand species-habitat relationships. In our case, since we were focusing on the Whistling Warbler, we also did an additional five-minute point count just for it. For the first two minutes, we would play a continuous variety of Whistling Warbler calls and songs and visually looked for the bird to come in. For the final three minutes, we would turn off the playback, and listen to see if the warbler called back. At several locations, we also set out Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs), which are small devices that record bird songs for days at a time without us being physically present at the site.

All of this data was entered into eBird, available to local stakeholders and forever stored in the global database (see our Trip report here: https://ebird.org/tripreport/58880). Needless to say, Lisa, Mike, Jeff, Mike Akresh, and myself all got a crash course in Saint Vincent bird ID in the field.

So, how are the warblers doing?

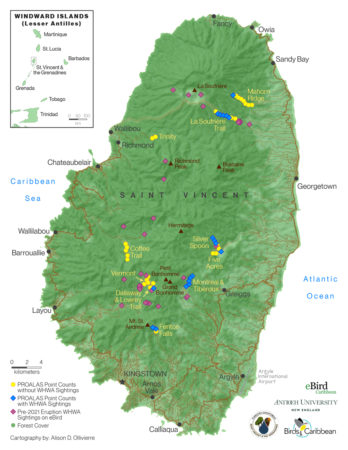

The good news is we found some warblers! After surveying 8 sites, 46 points, and conducting 100+ point counts, we detected the Whistling Warbler, by sight and/or sound, at around 35% of the point locations (see Figure 1). Warblers had higher abundance on the eastern (windward) side of the island compared to the western (leeward) side, and appeared to be present on steep, mountainous, wetter slopes with natural (non-planted) forest.

Interestingly, we detected a number of Whistling Warblers along the La Soufrière Trail, an area that was highly impacted by the volcano eruption, so the warbler seems to be doing ok despite the habitat destruction! However, the impacted northern areas were definitely quieter and a number of other forest birds seemed to be missing, like the Cocoa Thrush and Ruddy Quail-Dove. One hypothesis might be that the heavy ash deposits closer to the volcano affected insects living on the ground—the food resources needed by ground-foraging bird species.

We also noted that a few other bird species were especially rare on the island after the volcano eruption. For instance, we did not detect any Antillean Euphonias, and only briefly saw or heard the Rufous-throated Solitaire at two locations. The Green-throated Carib, Brown Trembler, and Scaly-breasted Thrasher also had fairly low numbers throughout the island. This may have been due to the habitat we focused on and/or the time of year of our surveys. Clearly, more surveys are needed to assess these other species.

Nature is resilient!

After traversing much of this island in search of the warbler, it is hard to imagine that this devastating eruption happened only one year ago. We saw the remnants of the ash on the trails; trees drooping over from the sheer weight of the volcanic ash upon their branches, and huge swaths in the north part of the island mostly devoid of large canopy trees. Yet, there was also life flourishing around us, green and growing up towards the light.

Glenroy commented that after the April eruptions, the forests were so eerily quiet, he felt like he was in outer space. He told us that in some areas, there was not one creature to be seen or heard for months, not even the ever-present mosquitos. Despite this devastating natural disaster, here we were though, both hearing and seeing many of the forest birds coming back. This also often included hearing the unmistakable crescendo whistling song of the Whistling Warbler, much to our delight.

Optimistic for the future: Our next steps

BirdsCaribbean, in partnership with Antioch University, SVGF, and others, are hoping to better understand how (and if) the Whistling Warbler and other species are recovering. Based on our knowledge of bird population resilience following catastrophic hurricanes, some species may quickly rebound to their former population sizes, while it may take years for other species to recover, and some may even become extinct. For instance, the Bahama Nuthatch, with a previously extremely small population, has not been seen since the devastating Hurricane Dorian passed through Grand Bahama island in 2019.

Next steps are to further examine the audio recordings we collected, carry out more surveys, and conduct a training workshop next winter to help build SVGF’s capacity to continue to monitor the warbler and other forest birds next year and in future years. We also plan to work together with SVGF to write a comprehensive Conservation Action Plan (CAP) which will help guide monitoring and conservation of the warbler for many years to come.

Finally, we will work with SVGF to elevate the status of the warbler in the eyes of locals—educate about this special little bird through school visits, field trips, and a media campaign. This endemic bird will hopefully become a source of pride, alongside the Saint Vincent Parrot, so that local people will join the fight to save it from extinction. It takes a village to work for the conservation of anything—especially birds—and we are excited to be partners on a fantastic project.

I keep returning to a quote from Senegalese conservationist, Baba Dioum: “In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.” Through collaboration with Vincentians and SVGF, I do believe we can better understand how this bird lives, and what this bird needs. It is, and will be, hard work. With help from Glenroy and other Forestry staff who have a wealth of knowledge and appreciation for the land and its wildlife, hopefully all Vincentians will come to know and love the Whistling Warbler as we have, and help us to conserve it and Saint Vincent’s other forest birds.

Acknowledgments

We thank Glenroy Gaymes for working with us in the field nearly every day, generously sharing his vast knowledge of the birds, plants, and other wildlife of Saint Vincent’s forests. We are also grateful to Mr. Fitzgerald Providence, Director of Forestry, and other SVGF staff for supporting our work, including Winston “Rambo” Williams, Lenchford Nimblet, and Cornelius Lyttle. Thanks also to Lystra Culzac for sharing her knowledge about the Whistling Warbler and St Vincent’s forest birds and providing helpful advice and insights to our field work. Funding for this pilot study came from BirdsCaribbean’s Volcano Recovery Fund—thank you so much to everyone who donated to this fund and to the “emergency group” that came together to assist with funding support and recovery . We also thank Antioch University’s Institute for International Conservation for providing additional funding.

Blog by Kaitlyn Okrusch (with Lisa Sorenson, Mike Akresh, Jeff Gerbracht, & Glenroy Gaymes). Kaitlyn is a graduate student at Antioch University of New England. She is obtaining a M.S. in Environmental Studies as well as getting her 7-12 grade science teaching licensure. She has worked and volunteered for various bird organizations over the past six years – both conducting research (bird-banding, nest searching) as well as developing curriculum and educating. These most recently include University of Montana Bird Ecology Lab (UMBEL), Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory (HRBO), and Owl Research Institute (ORI). Her passion is fueled by connecting people with the wild spaces they call home – especially through birds.

Help us to continue this work!

Once again, we thank the many generous members of our community who donated to help with the recovery effort for birds in St Vincent impacted by the April 2021 explosive eruptions of La Soufrière Volcano. If you would like to donate to help with our continued work with the Forestry Department and local communities, please click here and designate “St Vincent Volcano Recovery” as the specific purpose for your donation. Thank you!

*The “emergency group” that came together to assist with funding support and recovery of the St Vincent Parrot, Whistling Warbler, and other wildlife consisted of the following organizations: BirdsCaribbean, Rare Species Conservatory Foundation, Fauna and Flora International, Caribaea Initiative, Houston Zoo, Grenada Dove Conservation Programme, UNDP Reef to Ridge Project, Houston Zoo, IWECo Project St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and the Farallon Islands Foundation. We thank our amazing local partners SCIENCE Initiative, the St. Vincent & the Grenadines Environment Fund, and the Forestry Department for your support and hard work.

Gallery

Further reading: