While all birds are unique (of course!), Black Skimmers (Rhynchops niger) really stand out, with their long, knife-like, red-and-black bill with its unique long lower mandible. Unlike the related terns and gulls, eyesight is less important for catching prey; skimmers forage by slicing the water with their long lower mandible. Upon touching a small fish, their bill snaps shut to catch the fish. This feeding method allows for evening and nightly meals.

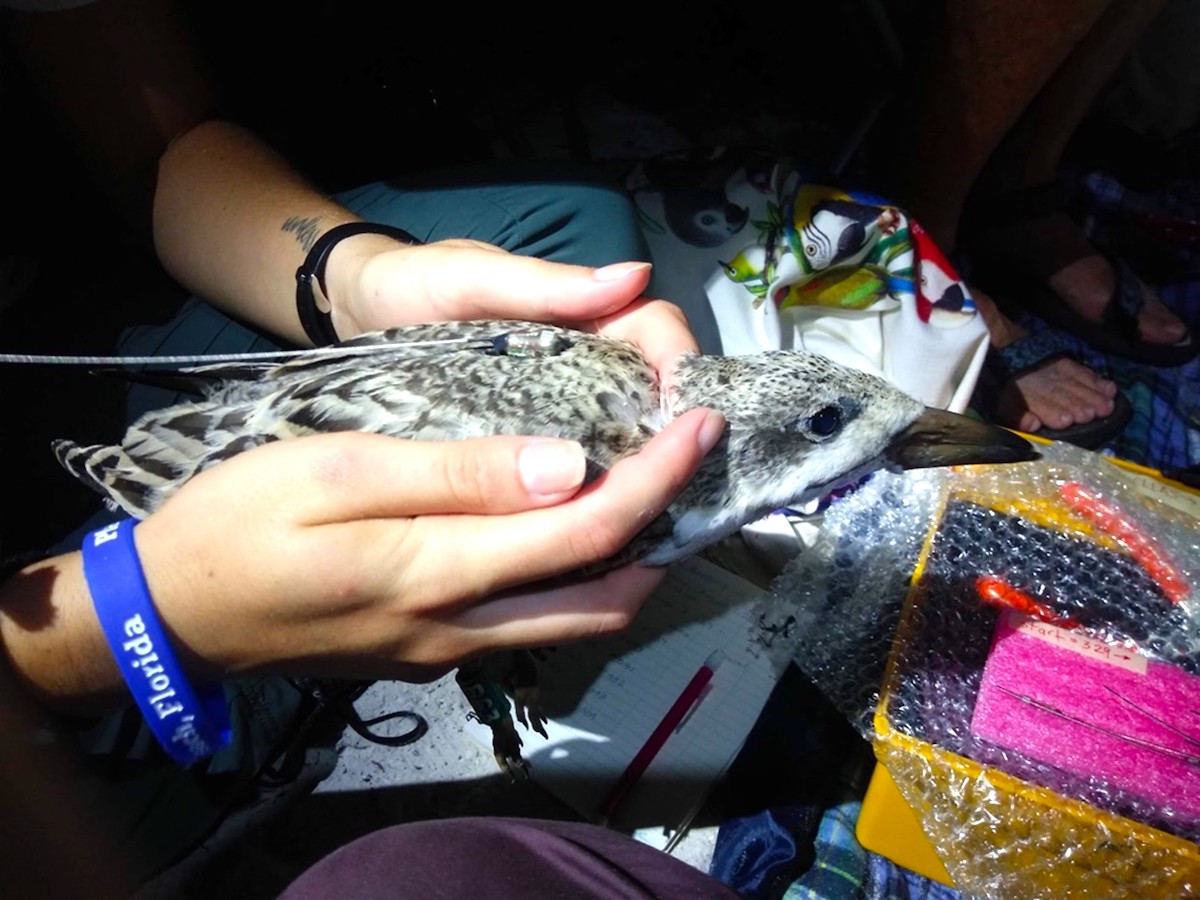

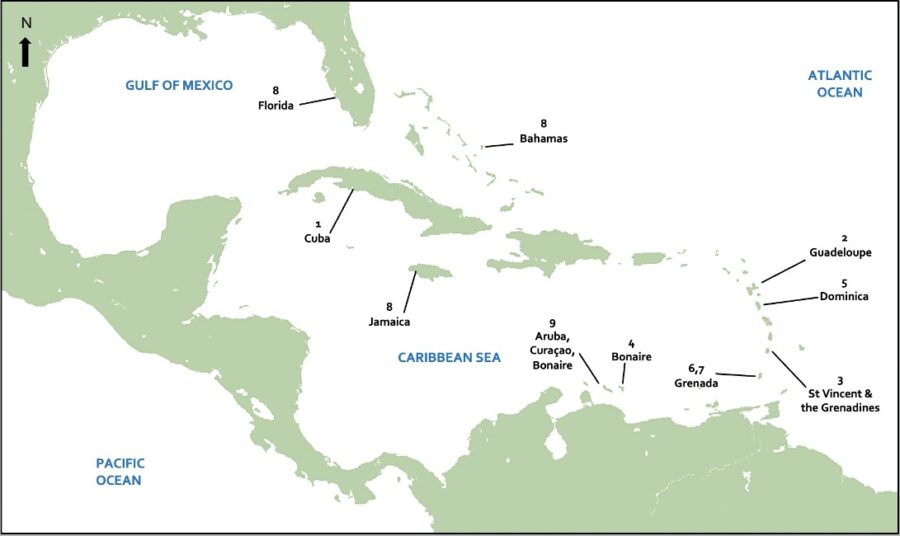

Dr. Kara Lefevre, now an Associate Dean of the Faculty of Science at Thompson Rivers University in British Columbia, became interested in skimmers while at Florida Gulf Coast University at Fort Myers, Florida. In their JCO article, “Insights from attempts to track movement of Black Skimmer (Rynchops niger) fledglings in the southern Gulf of Mexico with automated telemetry and band resighting,” Lefevre and colleagues tested whether they could track the movements of 3-week old skimmer youngsters that were raised at two colonies in south Florida, close to the Caribbean. Learning about dispersal of young skimmers from natal colonies would be of great value to learn about population dynamics and design conservation measures.

Although Black Skimmers are classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, skimmer colonies are negatively affected by human disturbance and modifications of their coastal habitat. Kara and her team attempted to use the Motus network to follow fledgling skimmers equipped with signal-emitting tags. Dr. Stefan Gleissberg, Managing Editor of JCO, asked Kara to tell us about her experiences while conducting her research—a more personal perspective that usually does not make it into an academic article.

How did you first conceive of this study, and what motivated you to conduct this research?

The Black Skimmer is known for its striking appearance and unique fishing behavior, and its large colonies along the Gulf of Mexico coast make it emblematic of Florida’s beaches. The proximity of Florida to the Caribbean makes it an interesting place to study skimmers because they occur across the Americas, yet little is known about juvenile dispersal and migration. We were interested in studying topics that support conservation of this majestic species while testing new methods of tracking bird movements.

Tell us about a memorable moment during field research or data analysis.

We witnessed many intense disturbances of these coastal breeding birds during our field studies. That includes human recreation along with major tropical storms like Hurricane Irma in 2017. A vivid memory is a prolonged Red Tide that was killing marine wildlife including skimmers and many other species of seabirds and shorebirds in southwest Florida in 2018. One day I was out surveying the colony at Marco Island from across a lagoon, and far in the distance noticed a large reddish hump on the shore that didn’t make sense. After zooming in with a spotting scope, I realized it was a dead beached manatee that was attracting scavenging animals. For me, that sad sight was emblematic of negative human impacts on coastal ecosystems, and a reminder of why we do this kind of research.

Tell us about a challenge you had to overcome; maybe an unexpected turn of events during field work or data analysis?

Working with finicky technology can create so many challenges! We faced hurdles related to permissions to do the research, technical challenges with setting up the array of telemetry stations, and storms that impacted receiving abilities. Probably the trickiest part was interpreting the data; we had to decipher whether automated telemetry detections in unexpected locations were actually real (spoiler alert: they were most likely false detections).

What are your hopes for what your research will lead to? Will this work impact your own research agenda going forward?

We hope this attempt to track juveniles will support broader study of skimmer dispersal and migration. In the years since we started our fieldwork, much of that is already underway. Newer and more powerful tracking technologies continue to develop rapidly, which is why researchers refer to this time as the “Golden Age” for bird migration research. In terms of my own research agenda, I plan to continue studies that support the conservation of seabird populations and their habitats while raising public awareness. The fieldwork for my PhD took place 20 years ago in Tobago—I would love to visit those rainforests again!

Anything else you’d want to share?

This is an exciting time for young people in the Caribbean who are interested in studying and protecting wildlife. With the availability of web conferencing and open tools, sharing of resources and expertise is easier than ever before. There is also growing attention to the need for training the next generation of conservation professionals in their places of origin—organizations like BirdsCaribbean are supporting that effort. Folks can also seek encouragement from professional groups that promote diversity and inclusion and provide resources for students and early-career professionals (see linked examples from the Society for Canadian Ornithologists, Association of Field Ornithologists).

In attempting to track the movements of Black Skimmer fledglings, Dr Lefevre’s findings raised several interesting questions—like why skimmer chicks from different colonies seem to move further south than others, and whether some skimmers might be moving from Florida even further afield to the Caribbean! Access Dr Lefevre’s full paper here to explore the study’s findings.

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology is a peer-reviewed journal covering all aspects of ornithology within the Caribbean region. We welcome manuscripts covering the biology, ecology, behavior, life history, and conservation of Caribbean birds and their habitats. This journal provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge.