Ashton Lagoon has re-awakened!

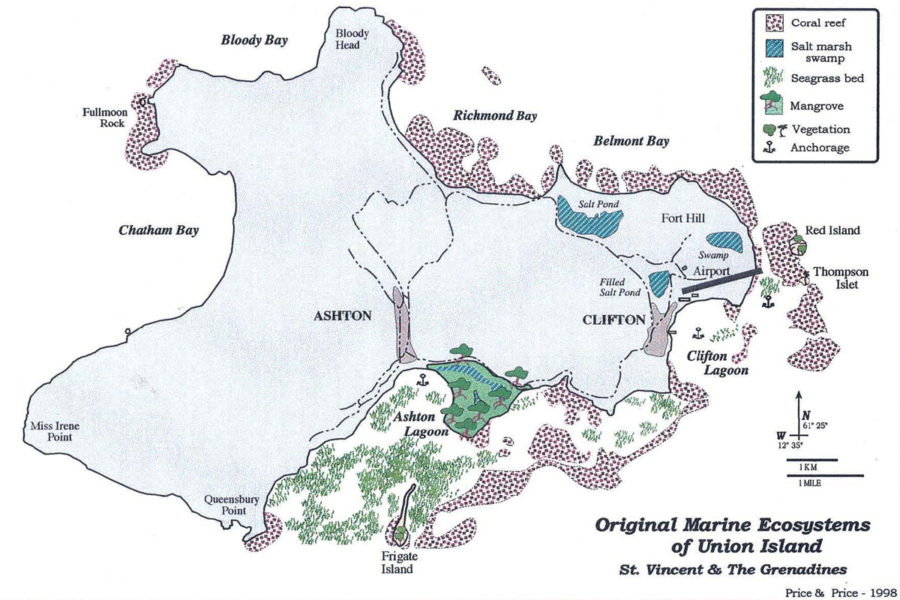

The local non-profit conservation organization Sustainable Grenadines (SusGren) welcomed guests to the lagoon’s (re)birthday celebration at its welcoming eco-friendly building on Union Island in the Grenadines on May 31, 2019. The building adjoins Ashton Lagoon, the largest natural bay and mangrove ecosystem in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. This area was legally designated a Conservation Area in 1987 and named as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International in 2008.

The story of Ashton Lagoon is worthy of honor and rejoicing, far and wide. The birthday party guests wore beaming smiles.

After 13 years of diligent work, SusGren, supported by its national and international partners, has succeeded in restoring the lagoon—not only for the well-being of the marine and bird life, but also for that of future generations of Union Islanders. Now it is transformed, blossoming into a beautiful place in which to learn, observe, and enjoy the bounties of nature.

On the final day of the BirdsCaribbean International Conference in Guadeloupe on July, 2019, keynote speaker and SusGren Executive Director Orisha Joseph presented an at times humorous account of the ambitious restoration project to a rapt audience (link to recording on our Facebook is here). Her presentation was punctuated by laughter and applause.

As the King said in “Alice in Wonderland,” it’s best to begin at the beginning. The tale of Ashton Lagoon began some 25 years ago, in 1994. That year marked its decline—the moment when an overseas investor said: “Let’s build a golf course over the mangroves. Let’s build a marina for 300 boats!” as Joseph described it. A causeway was to join Frigate Rock to Union Island.

The following year, the investor went bankrupt. The project was abandoned, but the damage had already been done. Joseph described the development as a “catastrophe.” The causeway and marina berths, constructed from metal sheet piles and dredged coral, blocked the circulation of water, causing immense harm to the mangroves, reefs, and seagrass.

Thereafter, Ashton Lagoon languished. With its stagnant green waters and its degraded mangrove forest, locals—including fisherfolk who passed through to their fishing grounds—shunned it. It became a lonely place, Joseph recounted during her presentation in Guadeloupe (which you can watch below!).

But hope appeared on the horizon. In 2004, Executive Director of BirdsCaribbean Lisa Sorenson visited Union Island to deliver a Wetlands Education Training Workshop. The group took a field trip to the damaged lagoon and learned about the heartbreak residents and fishers felt living with the eyesore of the abandoned and algae-filled lagoon. Sorenson began work to raise funds, and in 2007, thanks to support from the USFWS, SusGren and BirdsCaribbean held a 3-day Participatory Planning Workshop with local stakeholders. All agreed (including, thankfully, donors) that something must be done. But wasn’t this a Herculean task?

Yes, it was. The Restoration Project was a tough, complex undertaking, not for the faint-hearted. Initially, stakeholders developed a vision for the management and sustainable use of the area, and wrote funding proposals. Surveys and monitoring of the ecologically sensitive area were conducted. And then, there were the engineering issues to be resolved. Joseph reserved special appreciation for the man she called her “miracle worker,” Ian Roberts, Engineer/ Works Supervisor for the restoration.

Joseph emphasized that, apart from the onerous technical issues that besieged them (how to deal with those horrible metal piles?) another challenge was a less “concrete” one: How to keep the local community engaged and interested. They were impatient and SusGren’s credibility and reputation were at stake on this small island with a population of 3,500.

The group went through a funding crisis in 2014—one that Joseph looked back on with wry humor. In 2016, when the funds began to work out, the project’s three broad objectives were refined. These were to restore the ecosystem; to strengthen the community’s resilience to climate change, for its economic benefit; and to increase environmental awareness.

In 2018, the water began to flow again. The “miracle workers” had created some breaches in the marina’s piles for it to flow through …after 24 years. “The lagoon said, ‘I can breathe again!’” laughed Joseph.

There followed a frantic period of activity, as SusGren worked on several projects simultaneously. The mangroves were flooded with new water and circulation in the lagoon restored through strategic breaches and culverts in the causeway and marina berths. Two bird towers were built (one named after Lisa Sorenson’s favorite seabird, the Royal Tern). The Interpretive Centre was built and some moorings at Frigate Island were created. A nursery of 3,000 red mangroves was created; the seedlings, donated by the Grenada Department of Forestry. They were planted using bamboo, rather than PVC. A community-owned apiculture and honey production enterprise started up (“bees like black mangroves,” noted Joseph).

There are also two bridges. After the marina causeway and berths were breached in several places to allow the water to flow freely, the bridges were needed to provide access to the whole causeway—a part of which had been washed away by storms—as a place to walk and watch birds and wildlife. Now, the marina berths are turning into “little islets” with mangroves and other vegetation—growing well and providing a roosting place for birds and habitat for other wildlife.

Executive Director of BirdsCaribbean, Lisa Sorenson felt a great emotional investment in the project. “I could not stop smiling at the launch!” she confessed. “We are so proud of SusGren, their local partners and the donors for persevering with the project. This is a shining example of what can be done, with vision and determination, to right an environmental wrong that occurred many years ago. SusGren did not give up on Ashton Lagoon. Now it is a wonderful place for people—and birds—to visit. An American Flamingo showed up there recently, for the first time!”

BirdsCaribbean continues to provide support for clean-up activities, tree planting and additional signs for the bird towers.

Importantly, members of the public are using the Lagoon Eco Trail, including schoolchildren and teachers, eager to learn. In July, Danny’s Summer School on Union Island went birding at the Lagoon, identifying birds and exploring the trail. “This is what brings me most joy,” admits Orisha Joseph. Those years walking round the lonely lagoon with a colleague are gone. Now, at last, it is appreciated by local people. Non-motorized recreational activities have begun to take off. Kite surfing is booming!

Of course, more work remains to be done. SusGren and its partners now face a number of new and different challenges. They had not quite been prepared for a sudden flood of publicity (for example, in the Caribbean Compass yachting magazine) and the thousands of “likes” on social media. “We were even featured in the phone book!” said Joseph, with a hearty laugh.

The Ashton Lagoon Restoration Project is still lobbying the Governments of St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada—not only for funds, but to have the lagoon properly gazetted as a Marine Protected Area. On the ground, SusGren is tackling such issues as an invasion of cattle in the mangroves during the “let-go season” and management of vehicles. While increasing bird habitat, the organization wants to encourage community involvement that is orderly, and above all sustainable.

Now, the tides are flowing again in the lagoon, and the jewel-like waters, turquoise and opal, are clear and free. The mangroves are busy with bird life. Marine life is thriving. Pedestrian and boat access has been opened up.

In some ways, the story of Ashton Lagoon is almost like a Hollywood plot: disasters, disappointments, struggle and ultimately a sense of triumph. The less glamorous sub-plot is the sheer hard work and determination to see the project through, tackling red tape and unexpected obstacles, worrying about funding. It is the story of many conservation non-profits across the region.

The story of Ashton Lagoon has a happy ending—but actually it has not ended. Ashton Lagoon is cared for, again. It has a bright future, for wildlife and for people.

Partners and supporters of the Ashton Lagoon Restoration Project included: BirdsCaribbean; the Phillip Stephenson Foundation; The Nature Conservancy (TNC); the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Caribbean Marine Biodiversity Program (CMBP); the German Development Bank (KFW) through the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (5C’s); the Global Environment Facility–Small Grants Program (GEF-SGP); US Fish and Wildlife Service, Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act Fund, the St. Vincent and the Grenadines National Trust; Global Coral Reef Alliance; AvianEyes; Science Initiative for Environmental Conservation and Education; Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Transformation, Forestry, Fisheries and Industry; Construction Logistics, Inc.; Ministry of National Security, Lands and Survey Department; National Properties Limited; National Parks, Rivers and Beaches Authority; Grenadines Partnership Fund; University of New Hampshire; Union Island Environmental Attackers; Union Island Tourism Board; Union Island Association for Ecological Preservation (UIAEP); Union Island Ecotourism Movement, and others.

We invite you to enjoy the gallery of photos below. Hover over each photo to see the caption or click on the first photo to see a slide show.

Read more about the Ashton Lagoon Restoration Project (and also a project at Belmont Salt POnd) at the links below:

By Emma Lewis, Blogger, Writer, Online Activist, and member of BirdsCaribbean’s Media Working Group, based in Kingston, Jamaica. Follow Emma at Petchary’s Blog—Cries from Jamaica.