BirdsCaribbean is very excited to announce that we are launching a new bird monitoring initiative — the Caribbean Motus Collaboration. And we need your help and involvement! Read on to learn more about this program and how you can help.

What is Motus?

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System is a powerful collaborative research network developed by Birds Canada. Named after the Latin word for movement, Motus uses automated radio telemetry arrays to study the movements and behavior of flying animals (birds, bats, and insects) that are nano-tagged and tracked by Motus receivers.

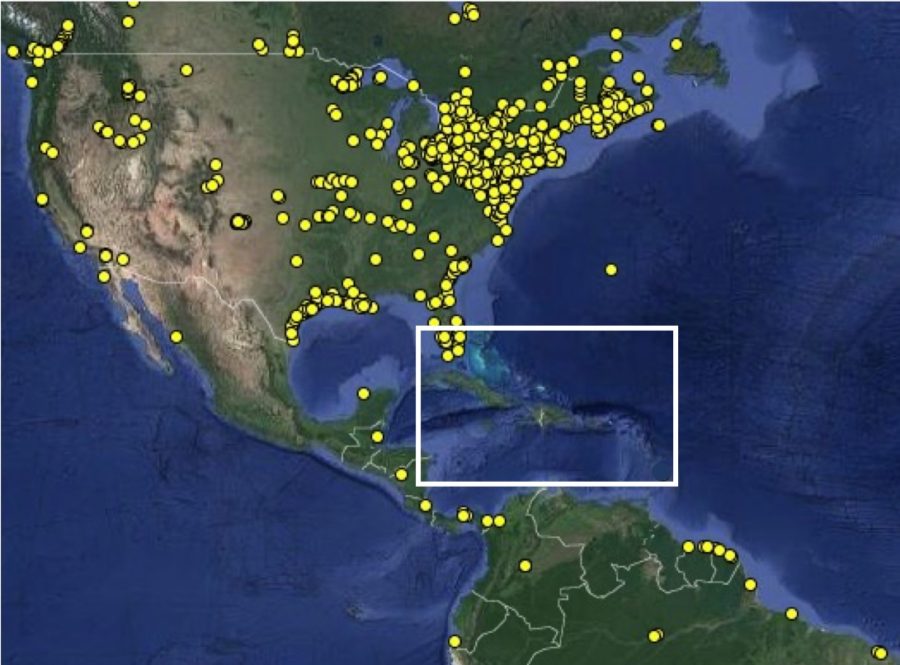

Motus’ main objective is to enable conservation and ecological research by tracking the movement of animals. The system consists of hundreds of receiver stations and thousands of deployed nanotags on 236+ species, mostly birds. Data from this network have already expanded our understanding of bird movements, including pinpointing migration routes and key stopover sites, as well as movements, habitat use, and behavior during breeding and non-breeding seasons. We are only just beginning to tap into the enormous potential of this new technology and growing network of partnerships and data sharing for conservation.

Motus technology is also a valuable educational tool that can advance conservation education both in and out of the classroom. Birds Canada and the Northeast Motus Collaboration have developed a curriculum that combines interactive classroom activities with Motus tracking tools that can be used to teach local children about birds, migration, and conservation.

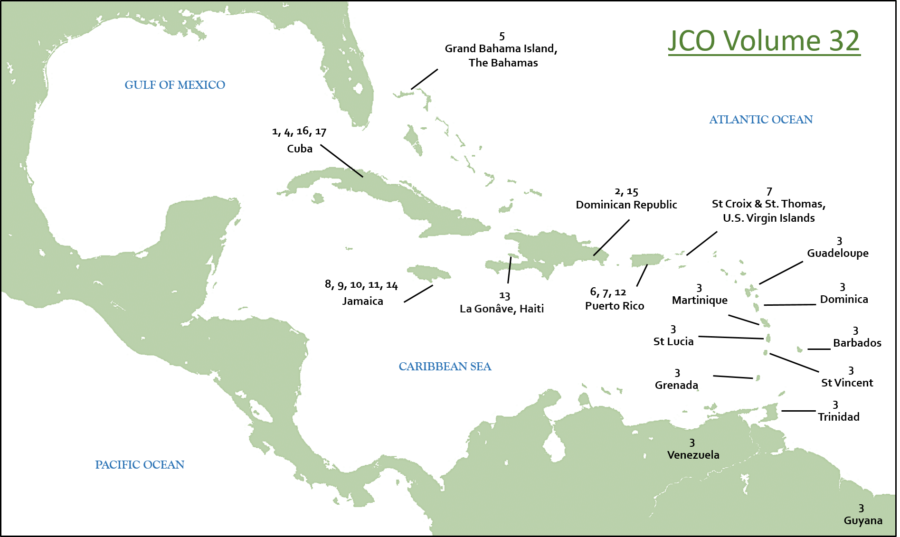

Expanding the Motus Network in the Caribbean

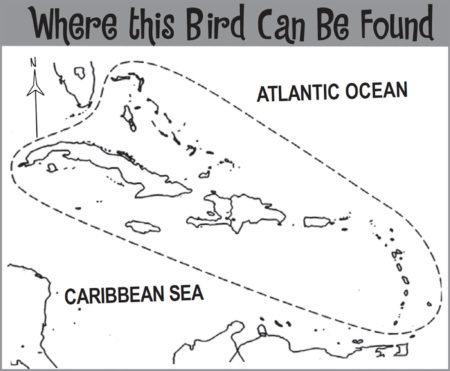

Motus is widely established in Canada and the US, and beginning to spread throughout Central and South America; however, there are currently no active receiver stations in the Caribbean. The more Motus stations we can put up, the more we can increase our understanding of where tagged birds are moving. In addition, many species of conservation concern that live in or migrate through/ to the region have not yet been tagged. We want to fill this critical geographical gap.

The Caribbean Motus Collaboration (CMC) is developing a multi-pronged strategy to expand the Motus network by installing and maintaining receiver stations in strategic locations throughout the islands, deploying nanotags on priority bird species, and implementing a specially adapted Caribbean educational curriculum.

Why is this Important?

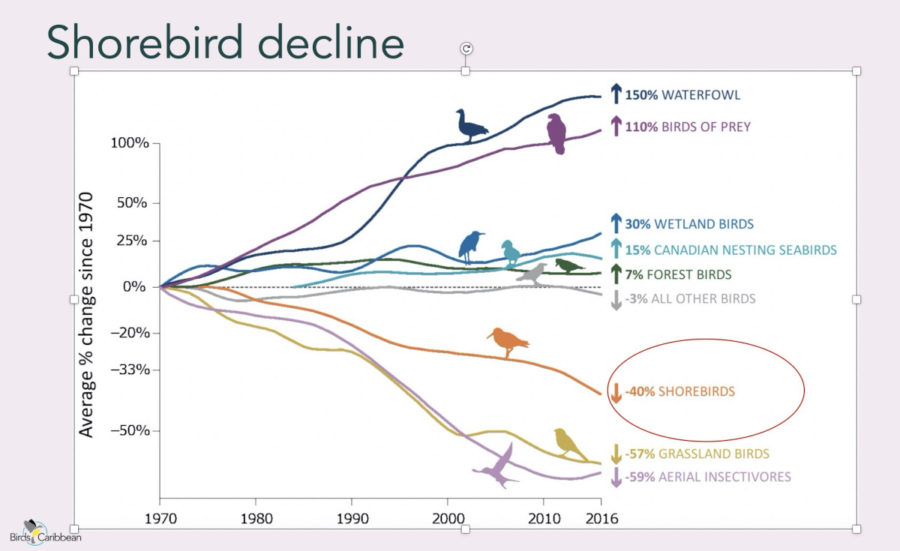

Our birds are declining at alarming rates.

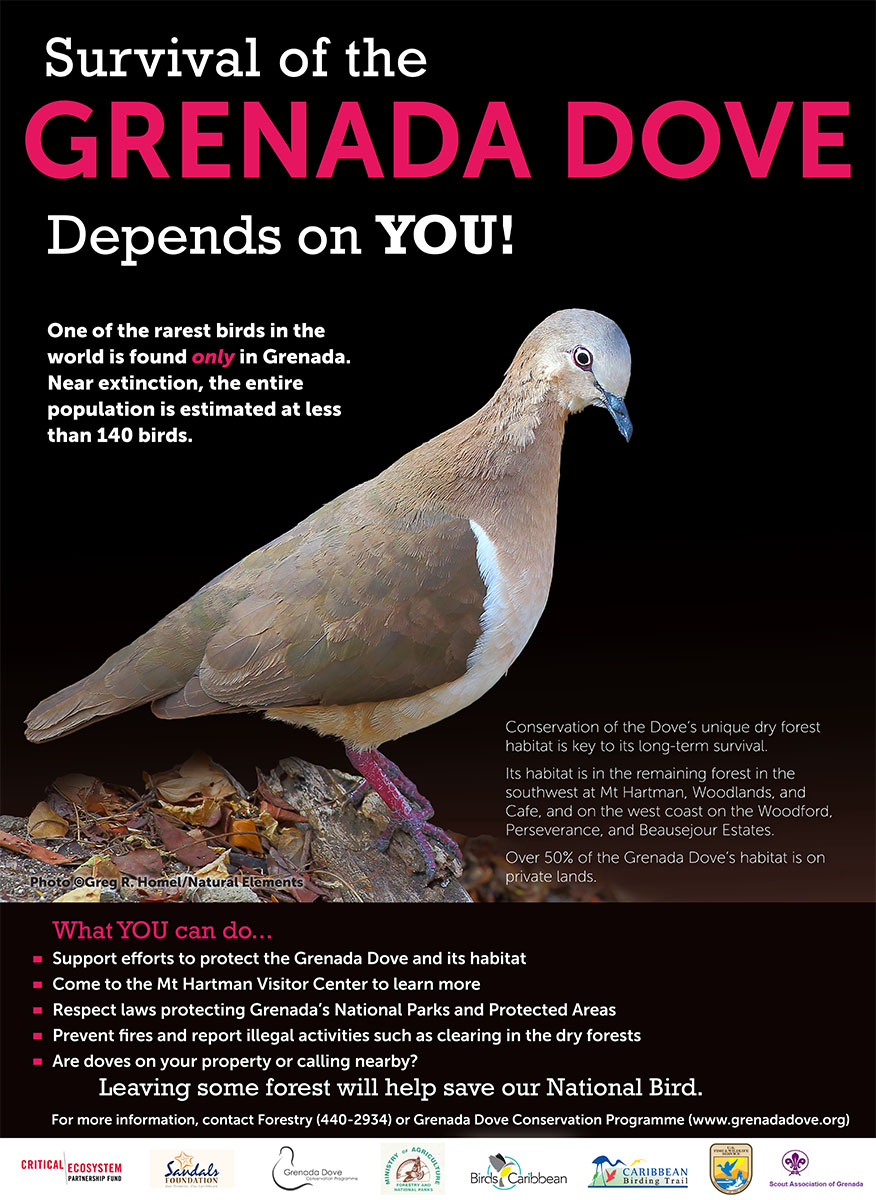

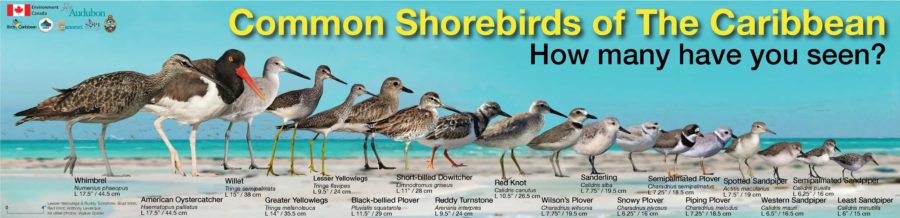

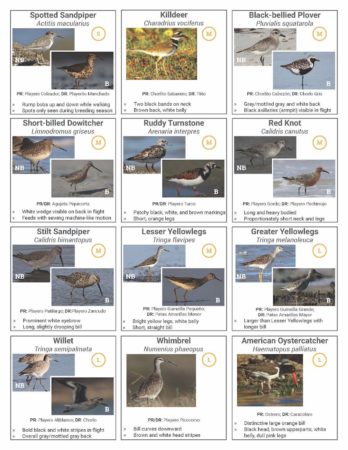

The insular Caribbean is a global biodiversity conservation “hotspot” that is home to over 700 species of birds. Roughly half of these bird species are residents in the Caribbean, including 171 that are endemic – meaning they are found nowhere else in the world! The other half are migratory, splitting their time between temperate and tropical habitats in the Americas, and shared among multiple countries along the way.

For some migratory birds, the Caribbean islands are the perfect winter retreat — they arrive in early fall and stay until spring. Others use one or more islands as stopover sites to rest and refuel as they fly between their breeding and wintering grounds further south. Whether they stay or move on, they are much-loved visitors, reflecting the seasons and inspiring our cultural expressions.

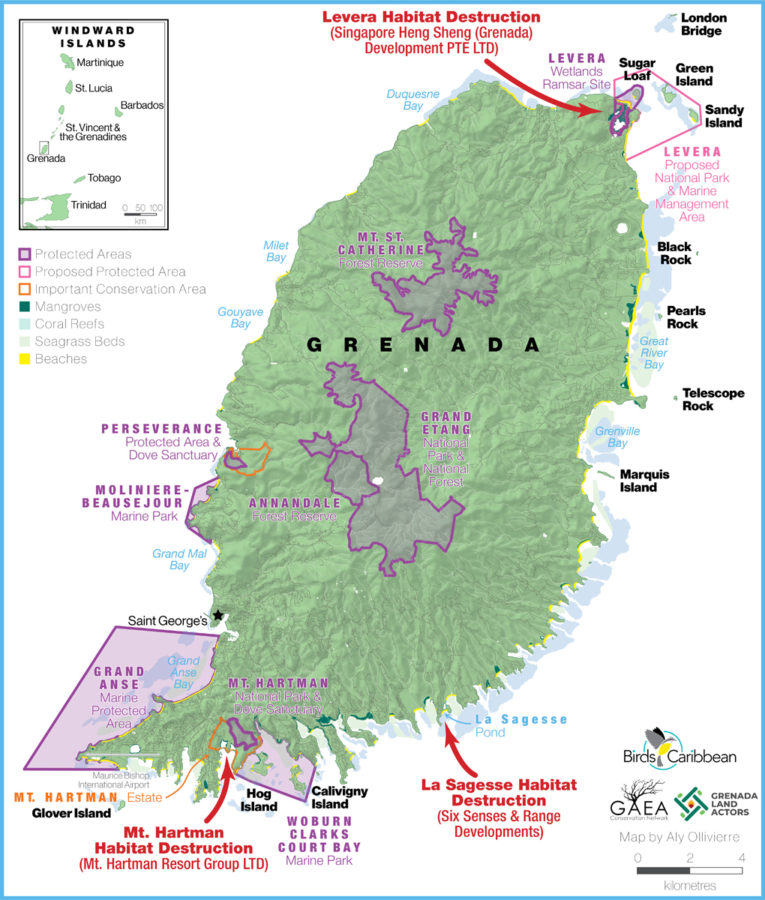

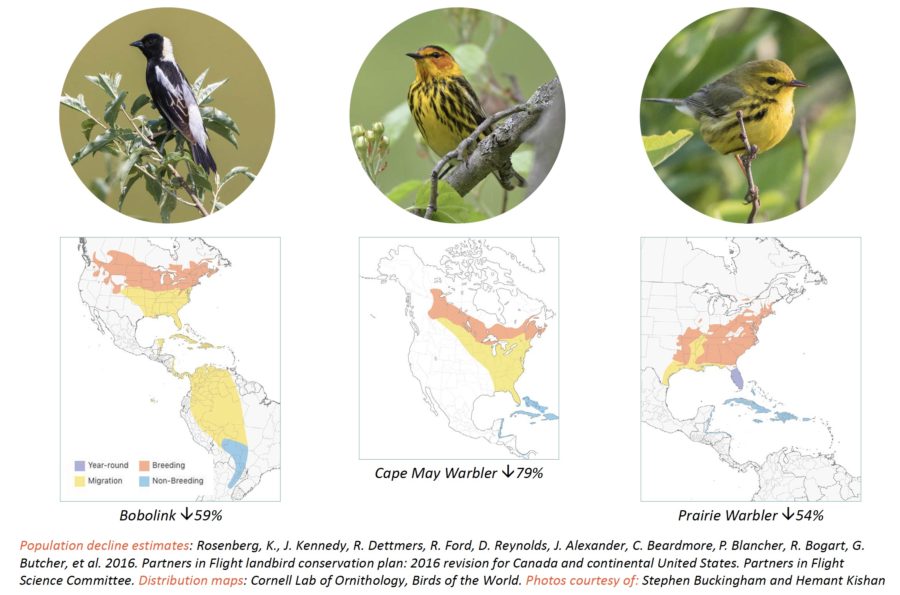

Unfortunately, bird populations are declining. Fifty-nine Caribbean species are at risk of extinction, listed as Vulnerable (30), Endangered (24), or Critically Endangered (5) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. A recent study found that nearly 30% of the bird populations in North America since 1970 have been lost, and Caribbean species are among the many that are in trouble.

Birds in the Caribbean face an entire suite of threats, including habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, and invasive species. In addition, climate change has become a constant danger to the region, not only to people, but also to wildlife. The Caribbean is experiencing increasingly intense hurricanes, long droughts, and dramatic changes to the marine environment. The threats are growing for our vulnerable birds, and we can’t afford to lose any more.

Needed now: An effective bird monitoring system in the Caribbean

Research on our birds has progressed considerably in recent decades, but we still lack basic information on many species. We need to understand them better if we are to save them.

We need to identify the most critical sites and habitats for our migratory, resident, and endemic birds, and we need to assess the threats they face. Importantly, we need to raise awareness about why all of this matters.

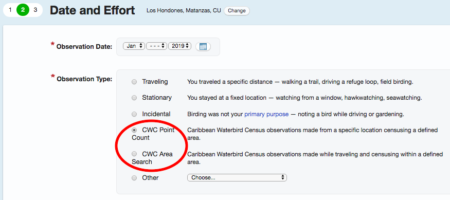

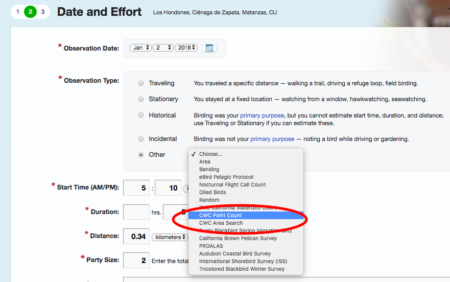

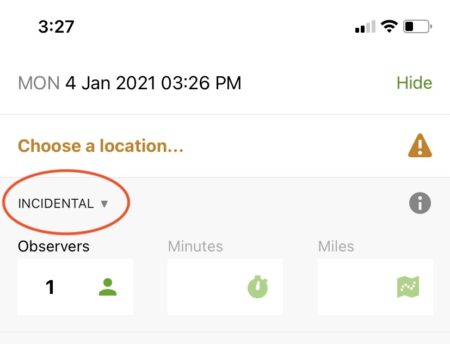

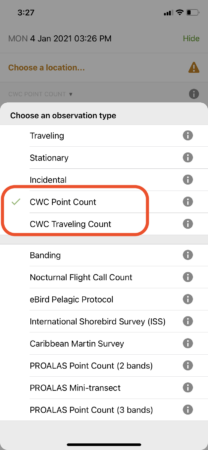

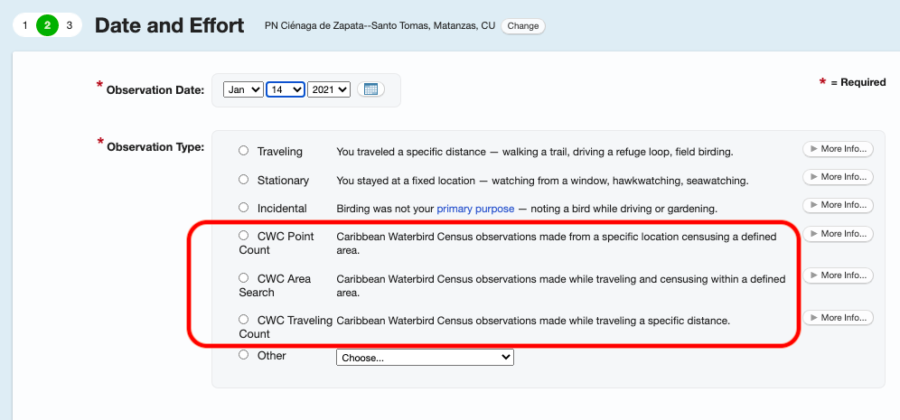

At BirdsCaribbean we partner with international, regional, and local partners to develop long-term monitoring programs, e.g. our Caribbean Waterbird Census program. We are using several strategic tools for doing so, and we are confident that the Motus Wildlife Tracking System will become an invaluable resource for strengthening our efforts.

The Caribbean Motus Collaboration (CMC) can inform and promote bird conservation

Our partners are eager to build the Motus network in the Caribbean. The initiative is gaining momentum quickly and the time to act is now! As a regional organization, BirdsCaribbean is keen to facilitate this effort and assist our partners.

Our collaboration will enhance the efforts of those working to grow the network in other regions of the Americas. And it will shed light on the movements and habitat use of bird species of conservation concern. This knowledge is essential to safeguarding birds throughout their full life cycles and reversing population declines.

Caribbean natural resource managers, including many of our partner organizations throughout the region, will be able to use information from the Motus network to identify the most important sites and habitats for our resident and migratory birds. Once identified, those in the Caribbean network and beyond will be able to focus our work on these most critical areas, alleviating threats and protecting these sites. By building the capacity to use this powerful tool, we will also be contributing to the development of local research and environmental education programs. The knowledge, skills, and appreciation for birds will multiply. It’s a “win-win” for the birds, and for those who work to conserve them in the region.

We Need Your Help!

To grow the CMC, we are seeking funding from granting agencies and private donors, and looking to establish partnerships with international and regional organizations, landowners, and businesses in the Caribbean.

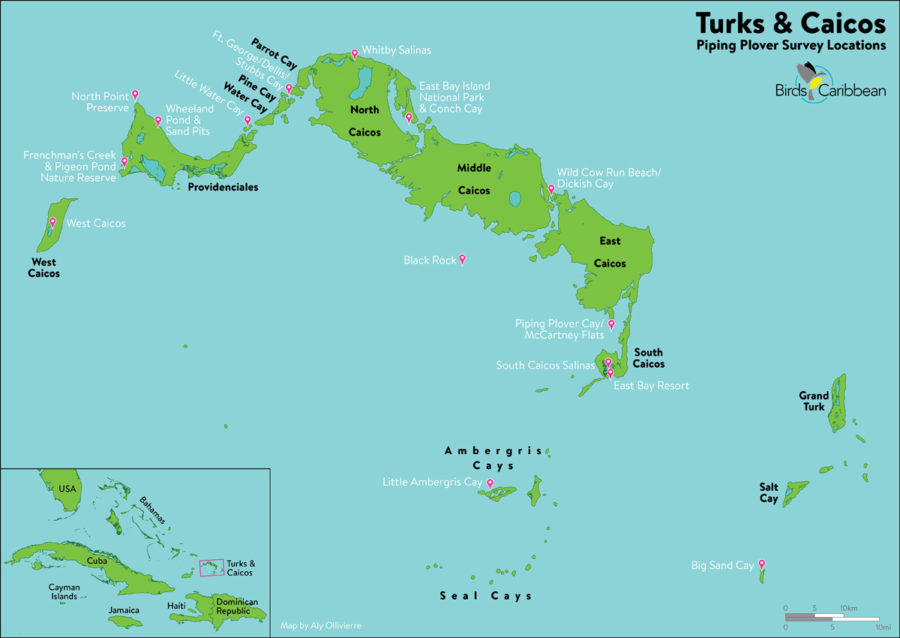

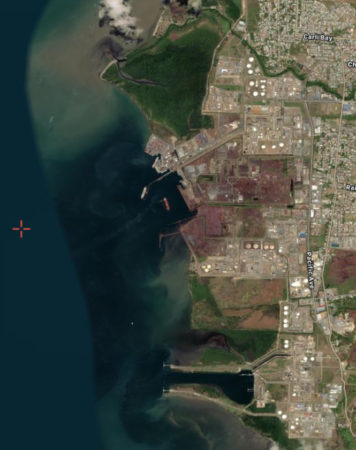

Can you suggest a good site for a Motus receiver station? Stations should be located in secure areas that are optimal for detecting movements of birds (e.g., migration flyways, prime habitat for resident and migratory birds). Receivers can be installed as independent structures that are powered by solar panels. However, installing a station on existing structures (e.g., building roofs, fire towers, abandoned telephone towers, radio towers, etc.), especially those with access to electricity, can significantly reduce costs.

Would you or your organization be willing to maintain Motus receiver stations on your island? Motus stations should require minimal maintenance. However, depending on the station setup, data might need to be downloaded a few times each year. It is also important to regularly check that the stations are in working order, particularly following a storm or other disturbance.

Are you interested in sponsoring a Motus receiver station or nanotags, or know of an individual, organization, or business who would be? The components of receiver stations cost approximately ~$4,800, and the total cost of a station (including installation, maintenance, personnel, etc.) is ~$10k. Nanotags, which will be deployed on priority species to track their movements, cost ~$225 each. But any amount is helpful! This is a highly tangible way to get involved in the conservation of Caribbean species.

Click here to make an online contribution.

*NOTE: This year, our fundraiser for Global Big Day (May 8th, 2021) will raise funds for the Caribbean Motus Collaboration. We hope that you will participate – stay tuned!

If you are interested in contributing to the CMC in any capacity, we want to hear from you! Please fill out this short survey so that we can gather information and follow up with you.

Special thanks to the Northeast Motus Collaboration for their generous help, advice, and encouragement in developing this project!

Learn more about Motus at the following links:

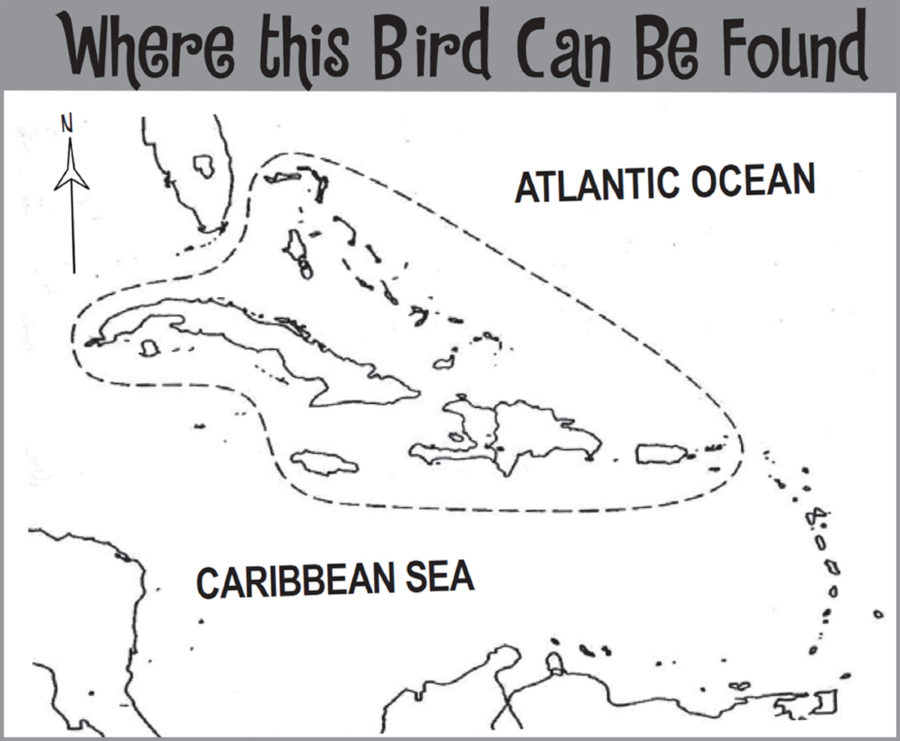

ou find?

ou find?