We have heard the painful stories of the 2017 hurricanes, which had devastating effects on humans and birds on some islands. How did our shorebirds weather the storm—especially those we are most concerned about from a conservation viewpoint? Elise Elliott-Smith shares her story of post-hurricane surveys in the Turks and Caicos Islands in February 2018.

For the past three years, I have been privileged to work with an international team of scientists led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center. Working with local partners and other international partners we have conducted surveys for Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) and other shorebird species of conservation concern in the Turks and Caicos Islands.

The Charming Piping Plover

The Piping Plover is a small, round-bodied shorebird, with a charming, big-eyed look. It breeds on beaches in the interior and Atlantic Coast of the U.S. and Canada, migrating to beaches in the southern Atlantic U.S., the northern West Indies, and across the Gulf Coast into northern Mexico. There are three discrete breeding populations, all of which are listed as endangered in Canada, and threatened or endangered in the U.S.

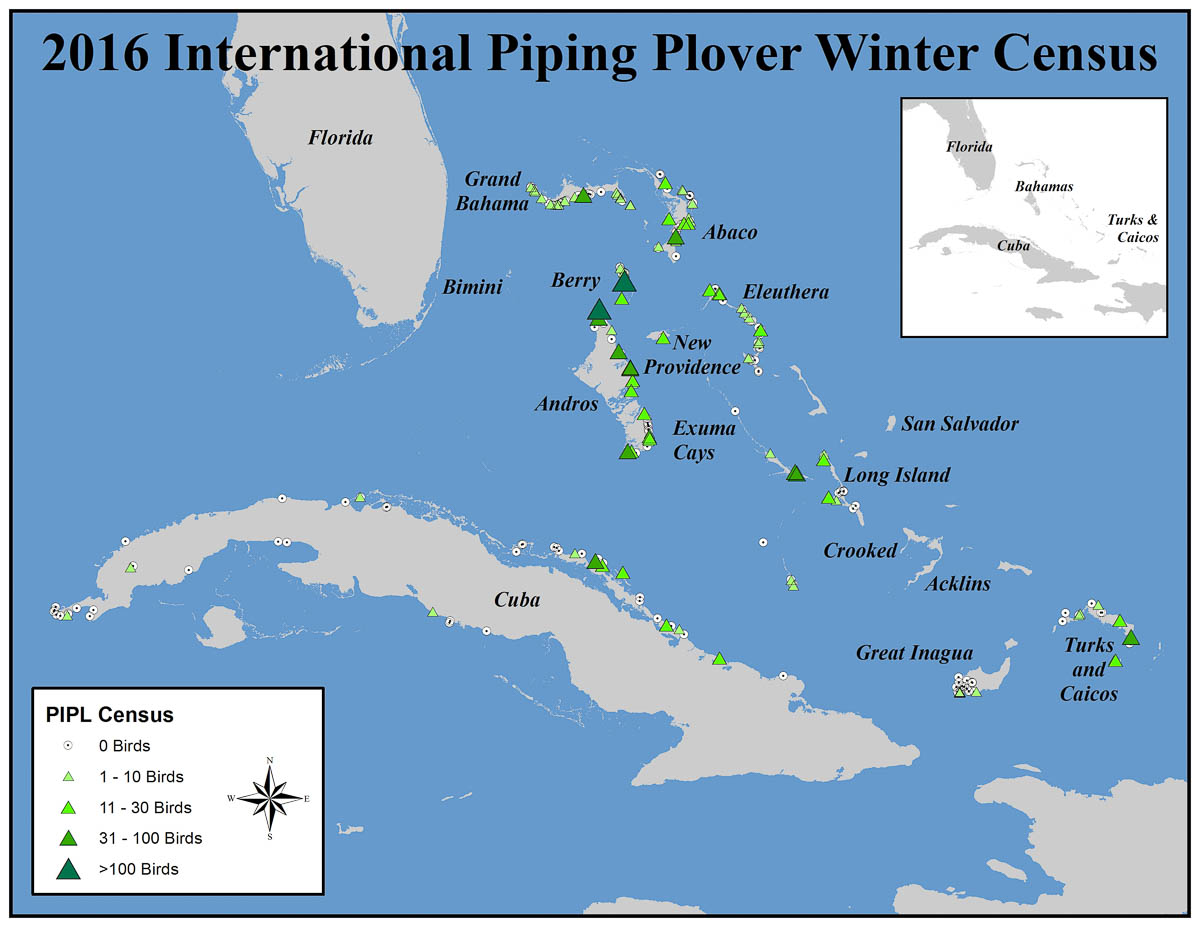

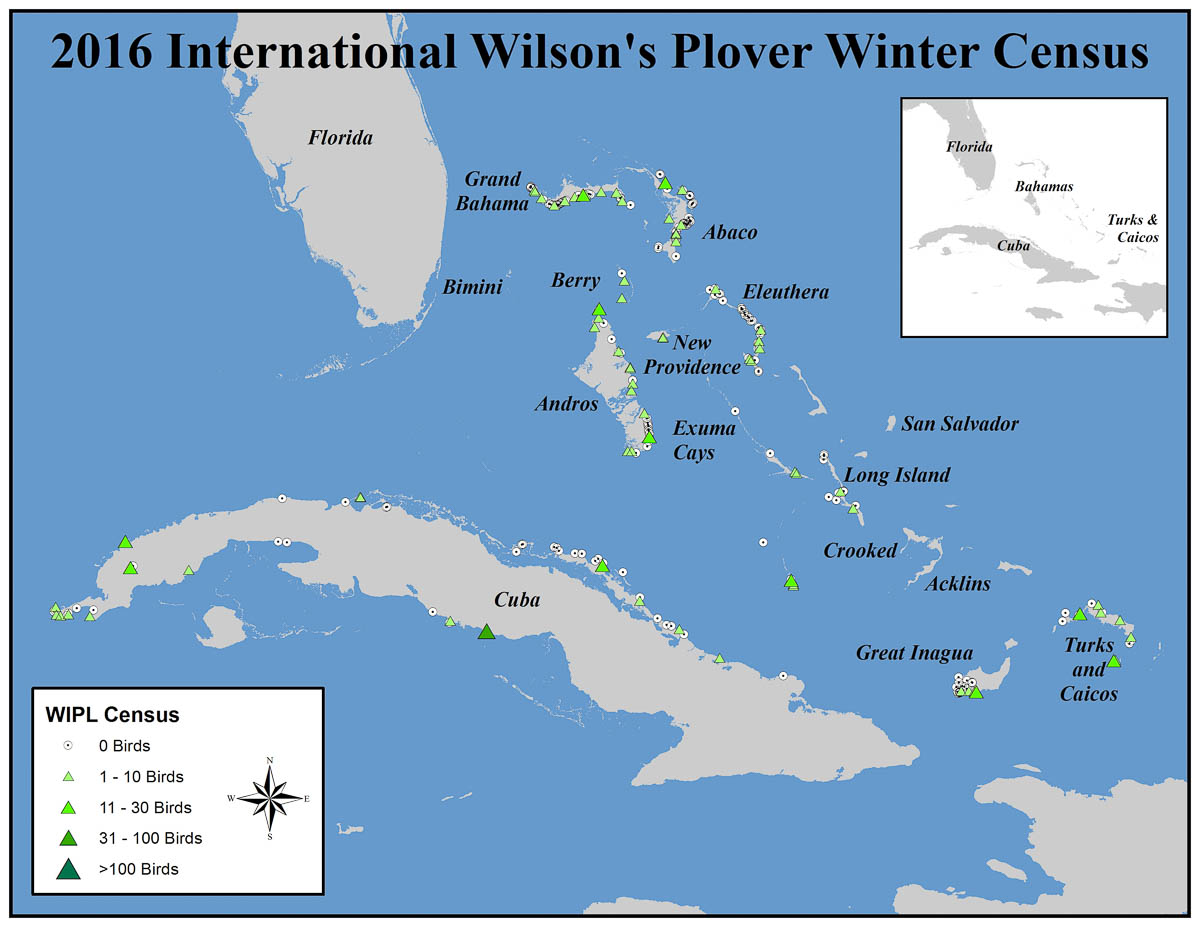

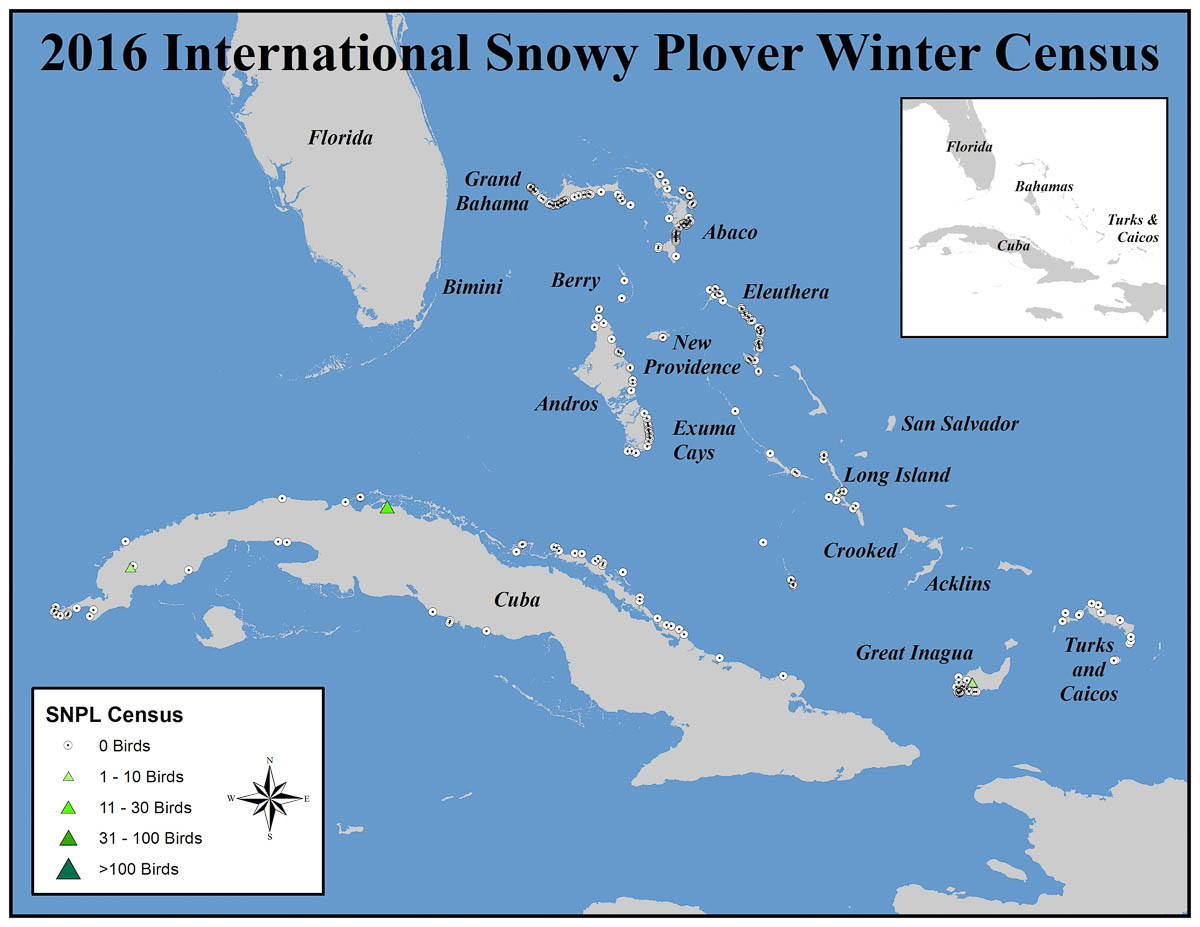

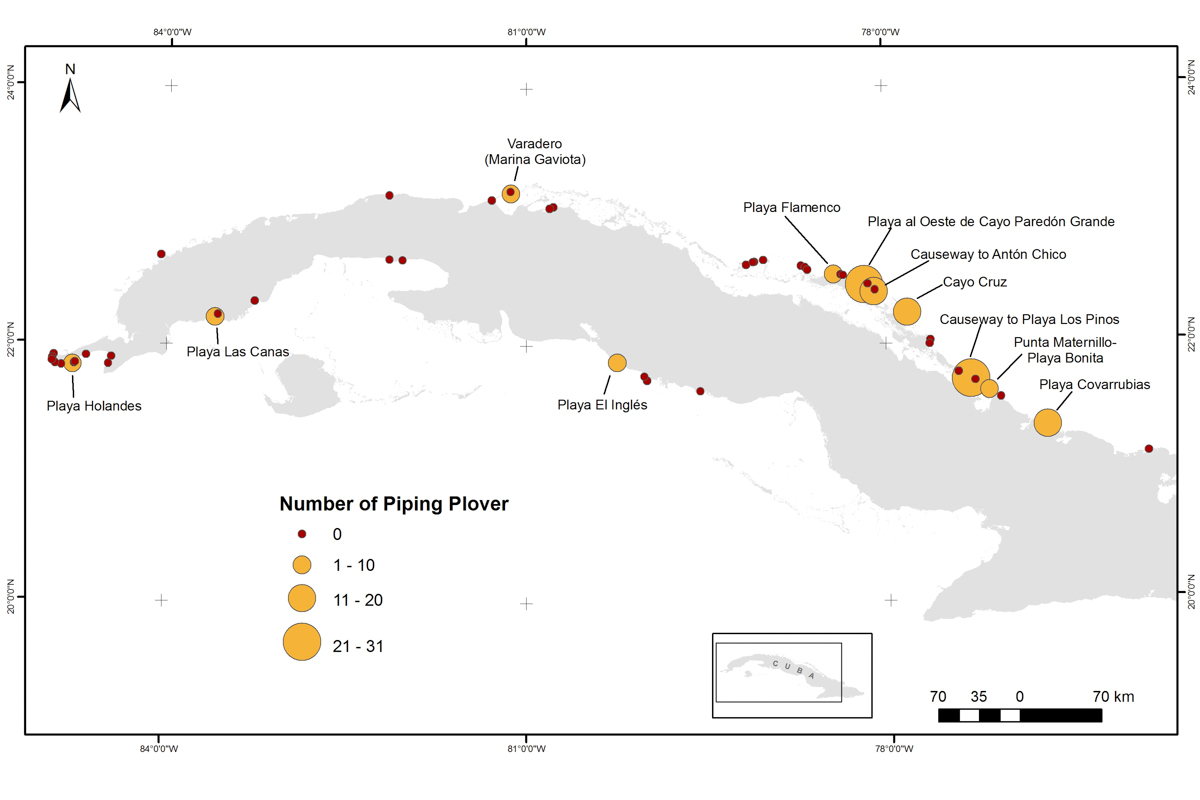

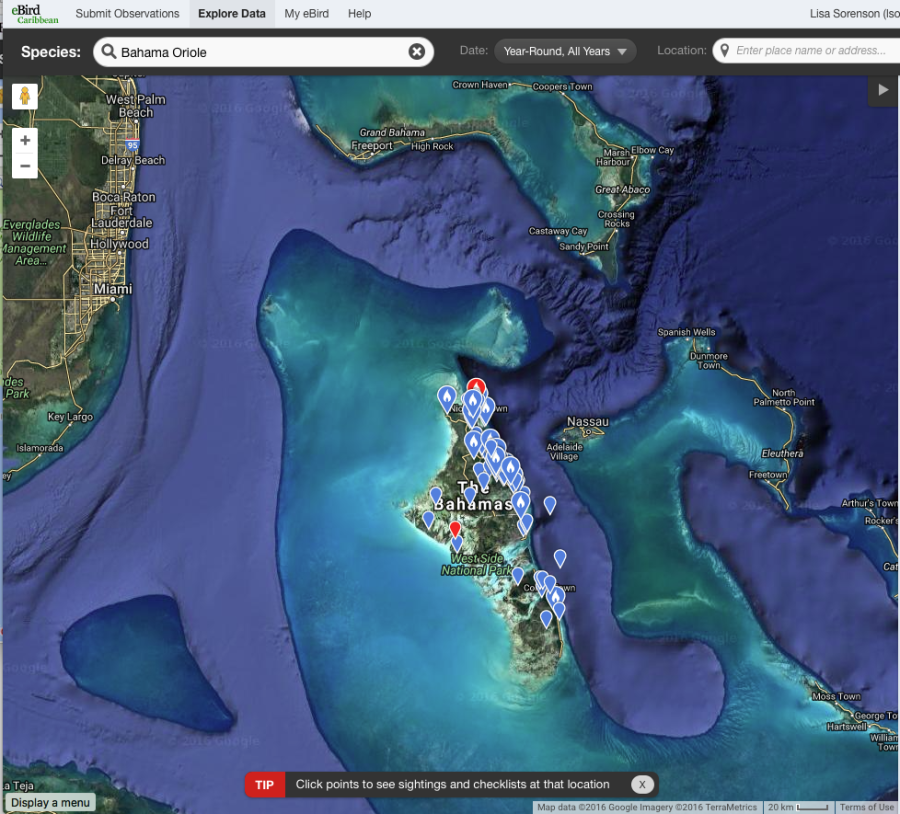

Fifteen years ago, no one knew that large numbers of Piping Plover winter in the Bahamas and northern Caribbean. But there was a surprise in store. During the 2011 International Piping Plover Census, it was discovered that around 1,000 birds wintered in the Bahamas. So, searching the Turks and Caicos Islands became a priority for the next Census in 2016 (read about 2016 International Piping Plover Census here). Our 2016 search yielded almost 100 Piping Plover and we counted 174 during an expanded search in January 2017. During this search, we also tallied about 20 other shorebird species, many of which are declining in numbers, or are focal species of the Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative. These species included the Red Knot (Calidris canutus), which is also listed as threatened/special concern in the U.S. and Canada.

The Onslaught of Hurricanes Irma and Maria

On September 7, 2017, Hurricane Irma hit the Turks and Caicos Islands as a Category 5 storm with sustained winds of 175 miles per hour. Two weeks later, Hurricane Maria arrived, packing 125 mph winds and torrential rain. My thoughts were with my colleagues and friends in the Turks and Caicos Islands as the storms passed. Despite extensive damage, and a heavy blow to the islands’ infrastructure, everyone was safe; miraculously, there were no deaths in the Turks and Caicos Islands. And after hearing this, I started wondering about the birds.

Far from the storm, I saw images on my computer screen of the destruction to human property and then the video of injured and dead flamingos in Cuba. I reasoned that given the small size of the Piping Plover, they could likely hunker down in strong winds. Perhaps some were still on their southerly migration and had not yet arrived. But a Piping Plover is not large, nor is it pink. The plovers’ small sand-colored carcasses would surely wash away unnoticed. The truth was, I really did not know how the storms had affected shorebirds or their habitat. But we had collected comprehensive survey data on all shorebird species for two prior winters at many remote sites in the Turks and Caicos Islands. I was eager get back there and see what had changed.

Post-hurricane Surveys Show Drop in Piping Plover Populations

Planning and preparing for these excursions is always exciting and a bit stressful. Our colleagues at the Turks and Caicos Department of the Environment and Coastal Resources (DECR) wanted to conduct surveys but they needed assistance. Partners at the USFWS and Canadian Wildlife Service – Environment and Climate Change Canada (CWS-ECCC) were also interested in helping but there were a lot of details to work out and questions to answer. Would we get funding? Would we get government permissions? Would we have enough cash to pay for the boats? Would the weather cooperate during the surveys? And would the birds themselves cooperate? This year, however, there was one very big question constantly looming in my mind as I was trying to secure funding for surveys and plan for the trip. How had the hurricanes affected the birds and their habitat? Would they even be there this year?

Post-hurricane surveys finally became possible with the support of BirdsCaribbean, the Turks & Caicos Reef Fund, DECR, SWA Environmental, USFWS, CWS-ECCC and USGS. We had an excellent International team of surveyors, with the support needed for surveying remote cays. So I found myself flying into Providenciales, TCI on the evening of 30 January 2018. Under the cover of night, I did not get to see the turquoise waters or the tarped and patched roofs of houses damaged by the storms. But looking out the window the next morning I saw evidence of the hurricanes that reminded me the Turks and Caicos Islands are still recovering.

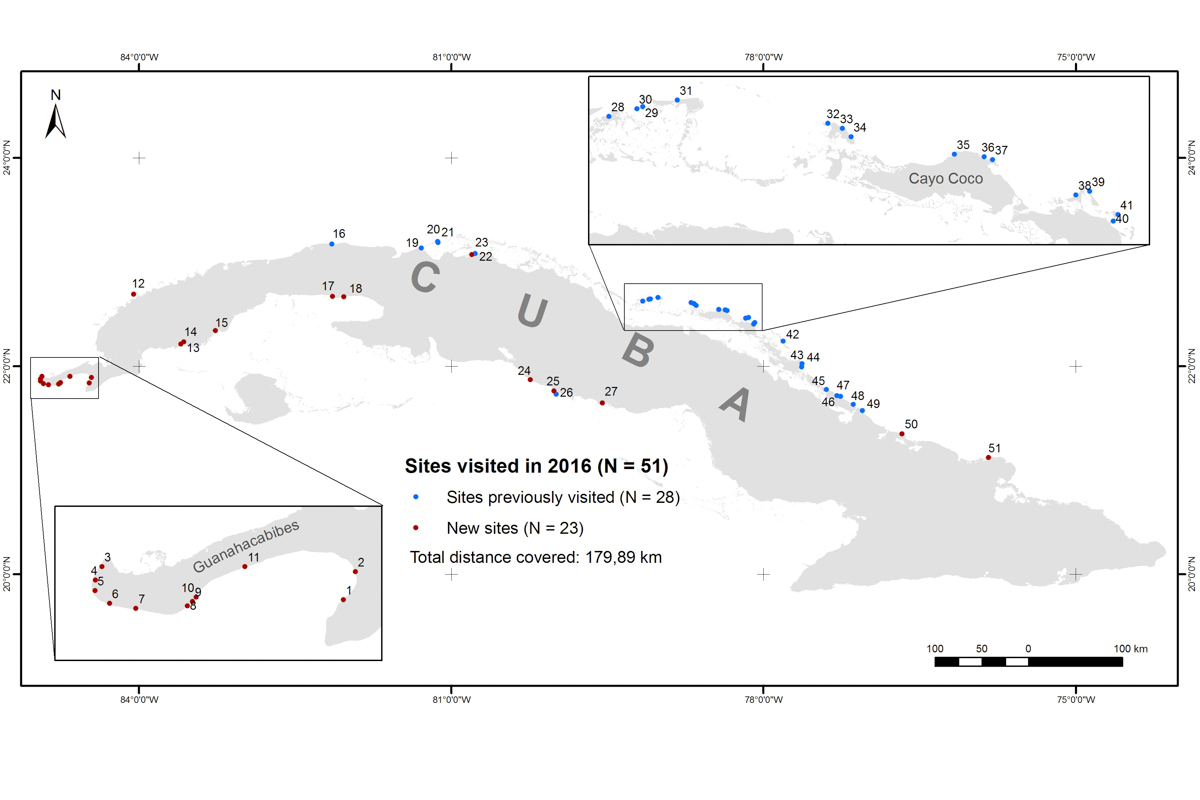

Over the next 10 days our teams conducted surveys on over 15 islands and cays in the Turks and Caicos Islands. We revisited every site where Piping Plover had been seen the prior year and surveyed a few new sites. In total, we saw just 62 Piping Plover. This was a far lower total than had been seen in 2017 or 2016. Counts of Piping Plovers were actually down at all of the sites surveyed in prior years, and they were completely absent from several sites.

Landscapes and Habitats Reshaped by the Storms

The extent of damage to human structures varied from island to island. Similarly, some Piping Plover sites appeared largely unaffected by the storms, while other sites had been substantially altered. Little Ambergris Cay was one of the sites hardest hit by the storms. The habitat had changed drastically. Multiple sandbars were breached or washed away entirely, interior mudflats were flooded, beaches were over-washed, and the island was literally split in two. Piping Plover had been seen at multiple locations on this island in 2016 and 2017. Despite the habitat changes, there appeared to be quite a bit of suitable habitat remaining in 2018. However, when we conducted a very thorough survey, no Piping Plover were seen. Shorebird numbers in general were down.

Some of the most important sites seemed relatively unchanged. However, storm erosion can be insidious, leaving sites looking deceptively undamaged at first glance. One of the most important shorebird sites in the Turks and Caicos Islands consists of a handful of very remote, tidally exposed sand flats and a tiny island, south of Middle Caicos. At this site, there is only a single small rocky area exposed during high tides. Birds tend to roost in this spot until neighboring sand flats are exposed for feeding. In 2017 we had seen about 3,000 shorebirds of at least 12 species at this site, including about 400 Red Knot. It is hard to identify and count 3,000 shorebirds, especially when they are spread out and moving around, so we planned our surveys for high tide, when birds concentrate. The area appeared to be largely unchanged. However, there were only about 1,000 shorebirds, far fewer than the prior year. We stayed in the area for nearly an entire tide cycle, but much of the sandflats remained shallowly flooded, even at low tide, indicating sand was likely lost during the hurricanes.

The Fate of Missing Birds Largely Unknown

Our early observations add to mounting evidence that there may be immediate negative effects of hurricanes on local wintering Piping Plover and other shorebird populations. However, questions remain. As in the Turks and Caicos Islands, Piping Plover numbers were greatly reduced in the Bahamas after Hurricane Matthew, particularly in areas hardest hit by the storm (Matt Jeffrey and Walker Golder (National Audubon), pers. comm). However, it is not known if shorebirds are dying in hurricanes or leaving in advance of the storm and wintering elsewhere. Spotting marked birds again may be the key to understanding this question of mortality. During our surveys in the Turks and Caicos Islands we observed Piping Plover that had been marked on their Atlantic Coast breeding grounds in the U.S. and Canada. Piping Plover tend to be faithful to their winter sites. However, some marked birds seen in the Turks and Caicos Islands in 2017 were “missing” on 2018 surveys. We will be looking for these individuals on migration and breeding grounds this summer. Re-sighting them would indicate they survived the storm. We also hope to return to the Turks and Caicos again in early 2019 to see if these missing birds have returned.

So what of the birds’ uncertain future? How resilient are Piping Plovers to hurricanes over the long term? And how resilient are the ecosystems on which they depend? Will sand be deposited again where it was lost? And how are the invertebrates (aka shorebird food) affected by hurricanes? These questions need further study, especially considering that with changing climates, storms may become more frequent and intense. In addition to searching for marked birds, the next step in answering these question is seeing shorebirds return to their favorite haunts in the Turks and Caicos Islands in higher numbers next winter. If birds survived the storm, we might expect to see a rebound in numbers next year.

Caribbean Waterbird Census – An Important Tool

We were fortunate to have baseline data before the storm from our previous surveys to assess how well Piping Plovers had survived the 2017 devastating hurricane season. Our results highlight the importance of the Caribbean Waterbird Census (which we have contributed to during our surveys of the Turks and Caicos) and other surveys that provide critical information on bird species abundance and distribution. This helps us gauge avian response to hurricanes and our changing climate and suggests actions that we can take to help birds survive. We cannot prevent the hurricanes from coming. But there is a lot that can be done to protect the birds remote habitats from development and minimize human disturbance.

As I returned home, I felt relief that at least some birds survived the storm and very encouraged by the incredible international support for our work. As an international species of concern, the Piping Plover requires collaboration to conserve their habitats across the different phases of their life cycle. I am optimistic that with the help of many, we can come together again to answer remaining questions and take steps to protect this beautiful little bird.

You can help too! We are still learning about this species’ distribution throughout the Caribbean – so learn how to distinguish them from similar species (like Sanderling, Semipalmated Plover, Wilson’s Plover, and Snowy Plovers) and help conduct surveys. Be on the lookout on sandy beaches and tidal mudflats, look for bands and flags, take pictures of the birds you see, and report all your observations on eBird Caribbean (and any Piping Plovers to me as well please! Contact Elise Elliott-Smith).

Notes from the Field

Day 1: A very rainy adventure to cays between Providenciales and North Caicos with Caleb Spiegel (USFWS), Eric Salamanca and an intrepid boat crew from the Turks and Caicos Department of the Environment and Coastal Resources (DECR). Few birds are seen and no Piping Plover are seen on either of the cays where they were documented in 2016 and 2017. This could be due to tour boat disturbance seen at one of the sites, but it is easy to miss birds when it is windy and wet. Need to return for a re-survey in better conditions.

Day 2: After a morning flight to South Caicos, Caleb, Eric and I kayak to what had been the most important Piping Plover site during our surveys the prior two years, a small uninhabited unnamed cay that we’ve affectionately dubbed “Piping Plover Cay”. Looking out the window while the plane landed and driving to the end of the road to put our boats in the water, it appears that South Caicos was hit harder than Providenciales by Hurricane Irma, and lacks the resources of the more popular tourist destinations to make a speedy recovery. Many houses are still missing roofs, some are missing walls, and at least a couple have been leveled by the storm.

More power lines are askew or knocked down than remain upright. And the salt ponds are too deeply flooded to support small shorebirds. Surprisingly, “Piping Plover Cay” looks good and largely unchanged. However, conditions are windy with some rain and although we see some shorebirds, there are no Piping Plovers in the flocks.

Day 3: Jen Rock and Beth MacDonald, our Canadian colleagues (ECCC), arrived last night. The weather has cleared, and we finally find some Piping Plover!! Seven birds are seen on Dickish Cay, a small uninhabited cay where we had seen them during both of the prior survey years. In 2016, we had accessed the site by swimming across a channel from the end of the road in Middle Caicos and had found 11 Piping Plover on interior mud flats. In 2017 we accessed the island by boat, surveying it twice, and the high count had been 24 Piping Plover, including two marked birds seen on the sandy beach. Piping Plover tend to be loyal to their winter sites, so we look for the marked birds seen in 2017. They are not in our small flock but we do see two newly marked Piping Plover: one marked as a chick in Newfoundland the prior summer and the other marked a few weeks before Hurricane Irma while on a migration stop-over in North Carolina. Although the number of birds is lower than prior years, if anything the hurricanes seems to have had a positive effect on the Piping Plover habitat. Invasive Casuarina has been uprooted and sand has been deposited on the east side of the island, widening the beach.

Day 4: Our team is joined by Kathleen Wood (SWA Environmental) and we head out in the DECR boat to survey Little Ambergris. We split into three teams of two and are dropped off at different locations on the islands so that we can efficiently cover all the habitat. Two sandbars on the south side of the island have been entirely washed away, creating inflows and flooding. We realize that the inflow on the southwest side has broken all the way through to the north side of the island, splitting the island into two. One beach was totally over-washed, widening it by leveling the short vegetation. Twenty-five Piping Plover were seen on this island in 2016 and 29 were seen in 2017. None are seen on this survey and overall shorebird numbers are lower than previous counts. There still appears to be a lot of reasonable shorebird habitat, but much of the habitat is greatly changed. On our way back we stop at Big Ambergris Cay. It is our first Piping Plover survey on this island; we did not survey it previously because the habitat on aerial images did not look ideal. Hurricane damage is very apparent here as well as erosion of beach habitat and cliffs backing the beach. Many structures are seriously damaged. We see no plovers and few shorebirds on the mostly exposed, windswept beaches.

Day 5: Jen, Beth and Kathleen return to “Piping Plover Cay”. The conditions are good and they see 45 Piping Plover – including two birds that Beth banded in Nova Scotia the previous summer! Caleb, Eric and I do not have as much luck. We return to Dickish Cay but do not see any Piping Plover (they also may use neighboring Joe Grant Cay or Wild Cow Run beach but we do not have time to check there). Our expert boat operator, Tim Hamilton, shows us some habitat in Lorrimer’s channels on Middle Caicos that we had not explored in prior years. It looks like good shorebird habitat but we see few birds.

Day 6: Sandbars south of Middle Caicos. This is the site where we saw about 3,000 shorebirds last year, including Red Knot. We arrive close to high tide and go to the roost spot. The area around the roost is very shallow so we need to get off the boat and wade in waist-deep water a few hundred meters to survey. Caleb and Jen start surveying while Beth, Eric and I stay in the boat to check the other sandbars, which are all inundated. We return to the roost spot and help count. There are only about 1,000 shorebirds this year and around 40 Red Knot. We discuss why we are seeing such reduced numbers and whether some birds could be roosting in an unknown location. We decide to wait for the tide to fall and see if more birds arrive. The sun is setting with the falling tide so we leave just before low tide. Although it is a pretty extreme low tide, the multiple finger-like sand flats all seem to still be inundated. The habitat looked unchanged when we first arrived at the site that morning but it is likely that some of the sand has eroded. As we return to South Caicos the sun is setting with a squall in the distance and a rainbow over the turquoise waters.

Days 7-10: Caleb, Jen and Eric return to Providenciales and then to North Caicos where they survey with Naqqi and Flash (DECR). No Piping Plover are seen at the Northwest Point National Marine Park, where one Piping Plover was seen in 2017. Later, they return to re-survey islands between Provo and North Caicos in better weather than day 1, but still do not see any Piping Plover, and few shorebirds. However, they have luck on East Bay Island, seeing 10 Piping Plover where 16 were seen in 2017, including four tagged birds: two that were marked on breeding grounds in Canada and two at breeding sites in the U.S.

Beth and I split off from the rest of the group and travel to Grand Turk where we explore habitat and survey with Katharine Hart (DECR). I had not been to Grand Turk previously and while we see many waterbirds on this island, the habitat is not ideal for Piping Plover. On our second day, we take a very rough and wet boat ride to explore two nearby uninhabited islands, Cotton and Gibb’s Cay. Gibb’s Cay has some good habitat but it is frequented by cruise ships and we only see a couple shorebirds. The next day we take a bigger boat to Big Sand Cay. Katharine has been to the island before for turtle work (it is a National Sanctuary and the most important hawksbill turtle nesting site in the islands) and reports that it has been affected by the hurricane. A tidal surge likely washed out vegetation so that now the east and west side of the island are connected by sand flats in a couple of spots. The habitat looks very good on this island. We do see turtle nests but we don’t see any Piping Plover.

Many thanks to Caleb Spiegel, Beth MacDonald, Naqqi Manco, Kathleen Wood, Emma Lewis, and Lisa Sorenson for input on this article. And special thanks to DECR, BirdsCaribbean, American Bird Conservancy, Turks & Caicos Reef Fund, SWA Environmental, USFWS, CWS-EEEC, USGS, and Big Blue Unlimited for providing financial and other support for this research.

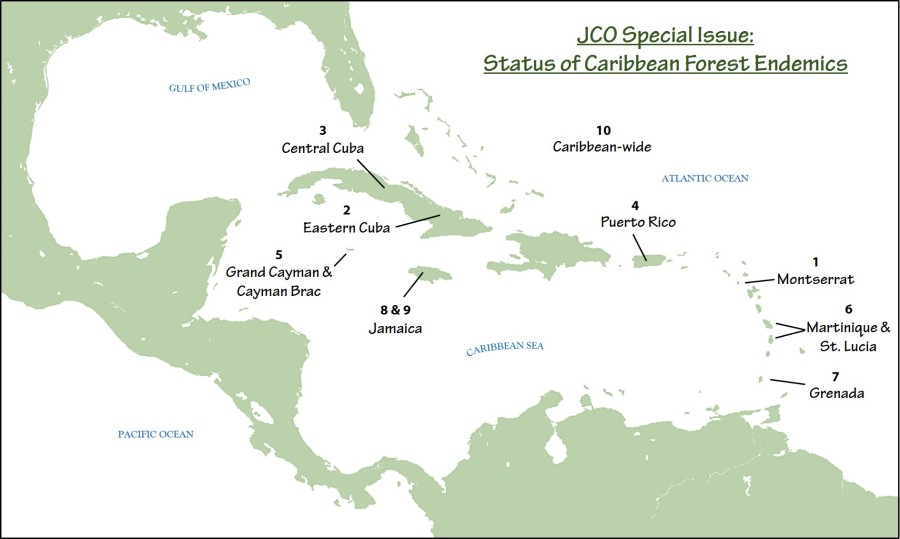

Our Special Issue starts off in the forests of Montserrat, a habitat heavily impacted by volcanic activity over the last twenty years. In Bambini et al.’s

Our Special Issue starts off in the forests of Montserrat, a habitat heavily impacted by volcanic activity over the last twenty years. In Bambini et al.’s  We move to the Greater Antilles where, in the face of recent extirpations from its former range, Peña et al. bring us in-depth news on the endangered Giant Kingbird’s remaining foothold in Cuba with their publication

We move to the Greater Antilles where, in the face of recent extirpations from its former range, Peña et al. bring us in-depth news on the endangered Giant Kingbird’s remaining foothold in Cuba with their publication  Moving westward across the Caribbean’s largest island, we are now presented with information on a newly identified population of Palm Crows that may exceed 200 individuals, thanks to recent work by Maikel Cañizares Morera in his publication

Moving westward across the Caribbean’s largest island, we are now presented with information on a newly identified population of Palm Crows that may exceed 200 individuals, thanks to recent work by Maikel Cañizares Morera in his publication  To the east, on the island of Puerto Rico, Anadón-Irizarry et al. provide us an invaluable update on the

To the east, on the island of Puerto Rico, Anadón-Irizarry et al. provide us an invaluable update on the  In Haakonsson et al.’s

In Haakonsson et al.’s  Our journey swings us back east into the Lesser Antilles to the neighboring islands of St. Lucia and Martinique, where Mortensen et al. report on the

Our journey swings us back east into the Lesser Antilles to the neighboring islands of St. Lucia and Martinique, where Mortensen et al. report on the  To the south lies the island of Grenada, where Bonnie L. Rusk has been undertaking

To the south lies the island of Grenada, where Bonnie L. Rusk has been undertaking  Lastly, we set sail back up towards the Greater Antilles, finding our way to the beautiful island of Jamaica, and in particular its Cockpit Country – a region known for its seemingly impenetrable (yet still vulnerable) geography of karst-limestone hills. Herlitz Davis’ publication on

Lastly, we set sail back up towards the Greater Antilles, finding our way to the beautiful island of Jamaica, and in particular its Cockpit Country – a region known for its seemingly impenetrable (yet still vulnerable) geography of karst-limestone hills. Herlitz Davis’ publication on  Pulling back to an island-wide view, Proctor et al.’s time censusing the remote corners of Jamaica for aerial insectivores completes an ongoing effort to determine whether any Jamaican Golden Swallows persist on the island in light of there having been no individuals reported since the 1980’s. The

Pulling back to an island-wide view, Proctor et al.’s time censusing the remote corners of Jamaica for aerial insectivores completes an ongoing effort to determine whether any Jamaican Golden Swallows persist on the island in light of there having been no individuals reported since the 1980’s. The  The Special Issue’s final publication is an equally important one in which we are empirically reminded of the unique niche that the JCO fills in the wider world of ornithological publications.

The Special Issue’s final publication is an equally important one in which we are empirically reminded of the unique niche that the JCO fills in the wider world of ornithological publications.

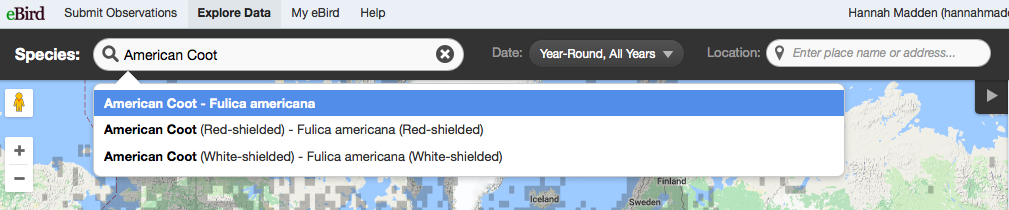

(Note: options may be considered “rare” in certain areas and will be hidden from the default list when you enter sightings.) All previous eBird Caribbean records of Caribbean Coot have now been listed under American Coot (White-shielded). Please use this option whenever you successfully identify a Caribbean-type coot and use the American Coot (Red-shielded) option for American-type coots. For more information

(Note: options may be considered “rare” in certain areas and will be hidden from the default list when you enter sightings.) All previous eBird Caribbean records of Caribbean Coot have now been listed under American Coot (White-shielded). Please use this option whenever you successfully identify a Caribbean-type coot and use the American Coot (Red-shielded) option for American-type coots. For more information