The 6th North American Ornithological Conference (NAOC) – 16-20 August 2016, Washington Hilton Hotel, Washington DC—BRINGING SCIENCE AND CONSERVATION TOGETHER #NAOC2016

BirdsCaribbean co-hosts an Outstandingly Successful Conference

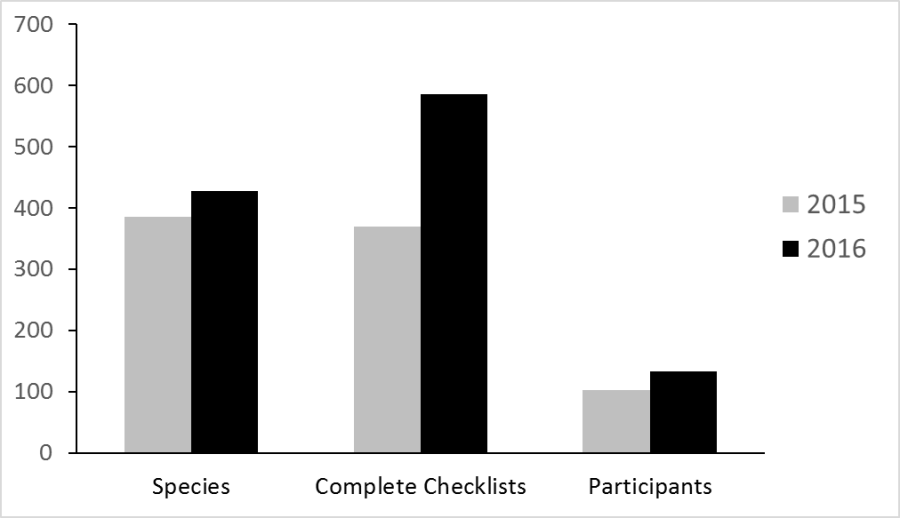

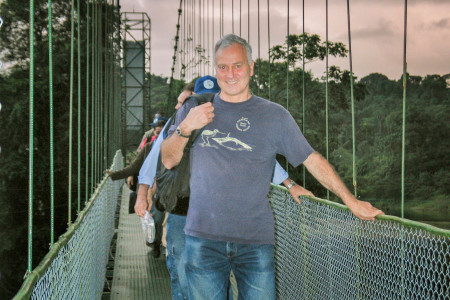

Between 16-20 August BirdsCaribbean joined with the Smithsonian Institution/Migratory Bird Center, American Ornithologists Union, Association of Field Ornithologists, CIPAMEX, Cooper Ornithological Society, Wilson Ornithological Society, Society of Canadian Ornithologists and Sociedad de Ornitologia Neotropical to co-host the sixth North American Ornithological Conference (NAOC) – the largest meeting of American ornithologists ever held. More than 2,000 scientists, students, and conservationists met in Washington DC to share their work on the theme “Bringing Science and Conservation Together.”

As co-host to the meeting, BirdsCaribbean helped with the preparations, planning and program development—not an easy task given the hundreds of symposia, sessions, lightening talks, and posters that were presented, not to mention the myriad social events, field trips and other opportunities for networking. Fourteen concurrent sessions kept everyone constantly on the move but it all worked beautifully, thanks to the brilliant leadership of the meeting Chair, Dr. Pete Marra, of the Smithsonian Institution, and many hard-working committees as well as the stellar work of the conference organizers Crabtree and Company.

For BirdsCaribbean, the conference was a fantastic opportunity to share information about the work being done in the Caribbean and the many urgent threats faced by Caribbean birds. We also learned new approaches and techniques, made new contacts, welcomed new members, and discussed fresh ways we can work together to address urgent Caribbean conservation issues. It would be impossible to list all the insights we gained from the meeting and the many outstanding talks, but we have mentioned a few below.

The Plight of Caribbean Forest Birds

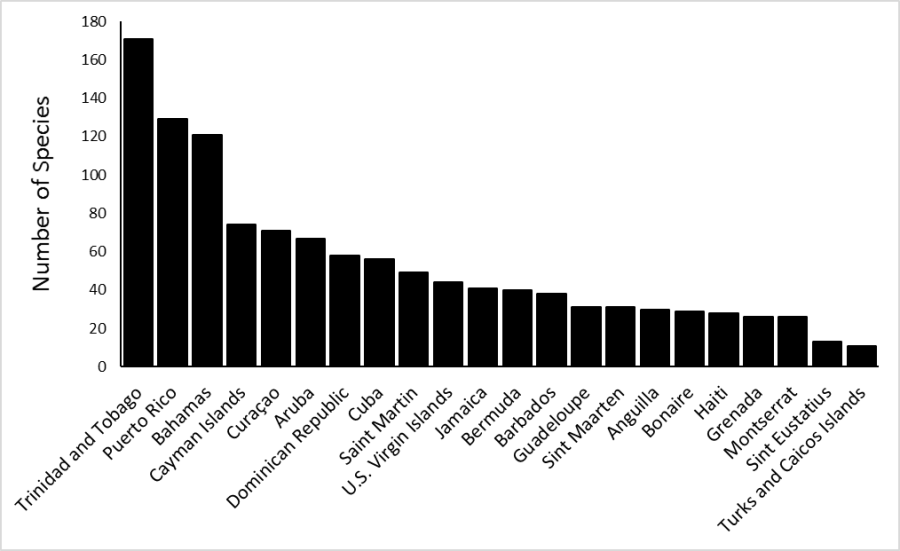

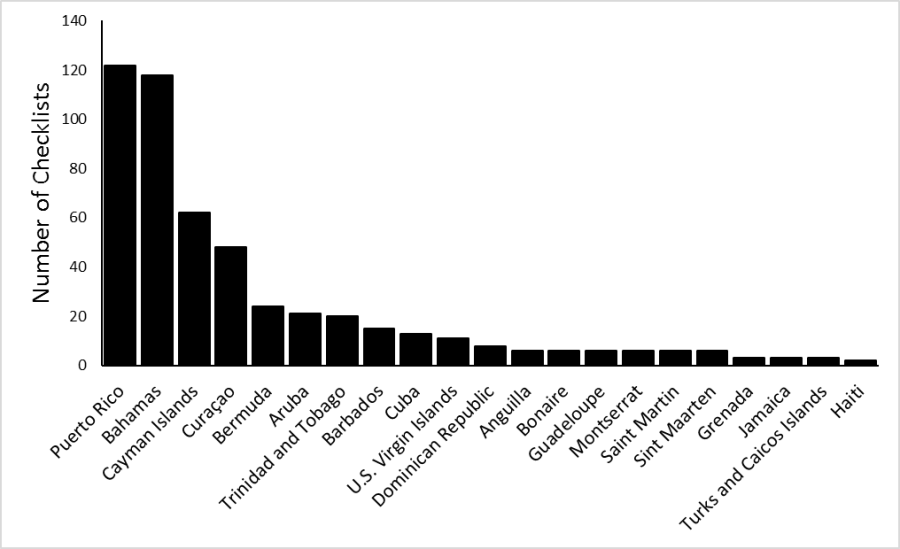

According to Howard Nelson (previous President of BirdsCaribbean and a current board member), of the 171 forest endemic bird species, an astonishing 86% do not have estimates of population size in the literature and 69% have no published research on conservation efforts. Research effort remains consistently low across both common and rare endemic species. Only the most charismatic groups, such has the parrots are relatively well known.

Dr. Nelson’s talk was the kick-off presentation of our symposia on August 18th highlighting recent research and conservation efforts on Caribbean forest endemic birds. Illuminating talks in our session included (PDFs are available below): Jen Mortensen, who presented strong genetic evidence for separate species of the White-breasted Thrasher on St. Lucia and Martinique. Frank Rivera updated us on numbers of the Critically Endangered Grenada Dove and Hook-billed Kite (less than 200 individuals of each species remain). Chris Rimmer pointed out that of the 31 endemics on Hispaniola, more than half are threatened and we know very little about any of these species. Jane Haakonsson showed data on how Cuban Parrot populations in the Cayman Islands were able to recover from hurricanes, but that these populations are now badly threatened by development. James Goetz summarized a decade of research and conservation progress on the endangered Black-capped Petrel – his concluding message was that the fate of the petrel, i.e., how the story ends, is in our hands.

Enthusiasm and a Bicycle

One surprising exception to the low level of scientific information to support conservation is Cuba. Dr. Lourdes Mugica of the University of Havana – a previous board member of BC – gave a fascinating plenary in which she talked about Cuban ornithology and her own research on wetland birds in the rice fields of Cuba. She reminded us that Cuban scientists continued to do first rate science when the only resources they had (because of the embargo) were enthusiasm and a bicycle. Later, as part of “Cuba Day,” Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology hosted an excellent symposium on Cuban Birds, with six Cuban ornithologists presenting. We live-streamed Lourdes’ plenary talk from our Facebook page – the video can be viewed at this link. More fun photos from the conference are posted here.

The Relative Importance of Conservation of Wintering Habitats for Migratory Birds

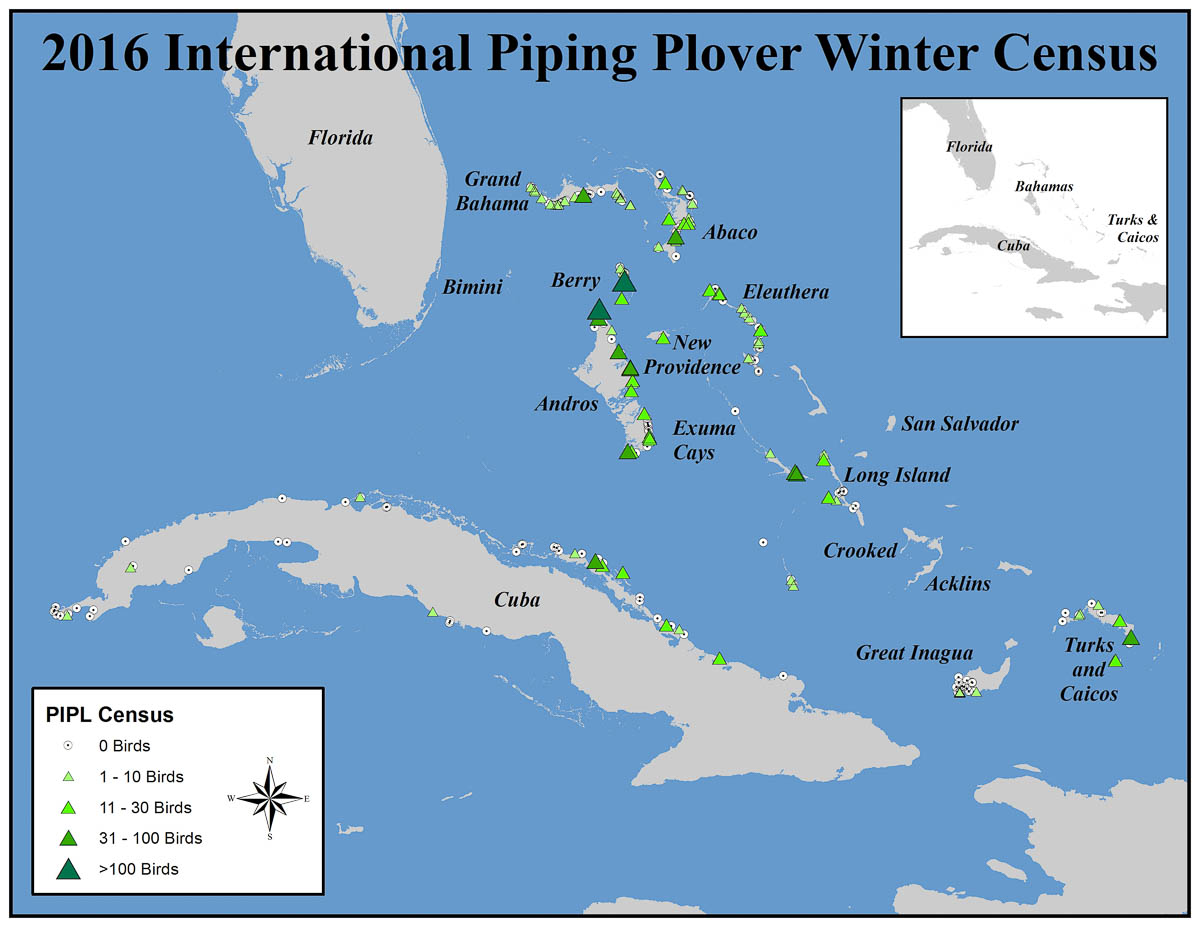

But it is not just Caribbean birds that are suffering declines. Mike Parr of the American Bird Conservancy emphasized the declines that many migrants are suffering and showed through scientific models that conservation on the wintering grounds is more likely to address these declines than anything that can be done on the breeding grounds.

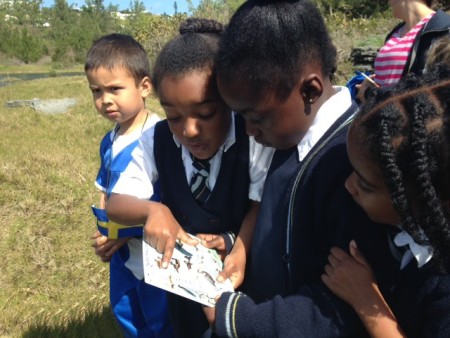

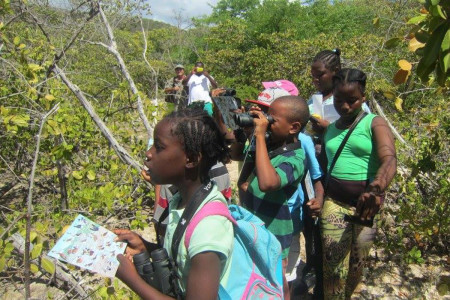

The Never-Ending Importance of Education and Awareness

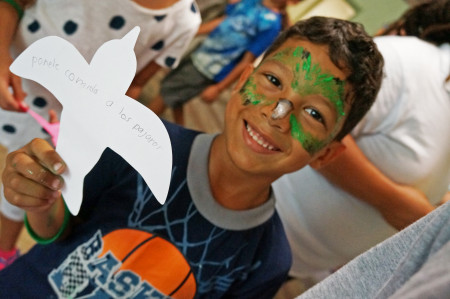

Science can identify the problems and solutions but only through education and awareness can we engage people to implement conservation measures. This was the theme of an excellent “lightening” session hosted by Environment for the Americas, at which both Lisa Sorenson and Leo Douglas presented papers on Caribbean outreach through the media, and an innovative study on impacts of environmental education on Jamaican youth.

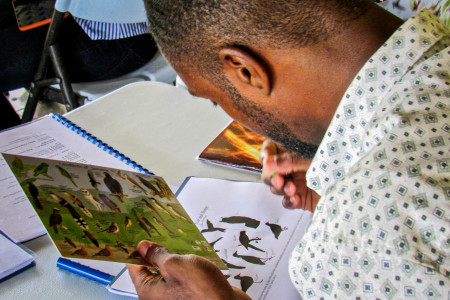

BirdsCaribbean Reaching Out

BirdsCaribbean was well represented in the sessions, workshops and symposia by a wide range of members and board members, young and old. We also took the opportunity to bring people together at a “Get-to-know BirdsCaribbean” social, at which more than 50 old and new friends came to meet, discuss on-going work and new directions, and drink rum to the sounds of Caribbean music. Our colorful booth in the exhibition hall was a hub for those interested in Caribbean birds, and was thronged by people who wanted to learn more about us and our work and buy T-shirts, field shirts, mugs, hats, artwork, crafts, and field guides to Caribbean islands. Many thanks are due to all our members and friends who volunteered to work at the booth and supported the booth by purchasing items throughout the meeting.

The future is Caribbean

There was much interest in two upcoming meetings in the Caribbean. BC shared the announcement of its next International Meeting in Cuba 13-17 July 2017. The NAOC announced that its next meeting will take place in Puerto Rico in August 2020. Both these meetings will help BC to raise interest in ornithology and conservation in the region.

For more information about the NAOC please visit their website, where you can download the program and abstracts.

The following is a list of papers presented at NAOC that mentioned the Caribbean. PDFs of some presentations are available for review (files are continuing to be uploaded).

Conservation of Caribbean Forest Endemic Birds Symposium (organized by BirdsCaribbean):

Red List Status of Forest Endemic Birds in the Caribbean. Nelson, Howard – University of Chester; Eleanor Devenish-Nelson – University of Chester; Doug Weidemann – BirdsCaribbean Journal of Caribbean Ornithology; Jason Townsend – BirdsCaribbean Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

Clear differentiation between island races of the White-breasted Thrasher (Ramphocinclus brachyurus), an endangered Antillean passerine. Mortensen, Jennifer, Tufts University.

Population Assessment of the Grenada Dove (Leptotila wellsi) and Hook-Billed Kite (Chondrohierax uncinatus mirus) using Distance Sampling and Repeated Count Methods. Rivera-Milán, Frank – US Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Branch of Population and Habitat Assessments

Hispaniolan Forest Endemics — Rare, Vulnerable and Understudied. Rimmer, Chris, Vermont Center for Ecostudies.

Conservation Status of the Cuban Parrot on Grand Cayman and Cayman Brac. Haakonsson, Jane, Dept of Environment, Cayman Islands.

A Decade of Advances in Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata) Research and Conservation. Goetz, James – Dept. Nat. Resources, Cornell University; Adam Brown – Environmental Protection in the Caribbean; Ernst Rupp – Grupo Jaragua; Anderson Jean – Société Audubon Haiti; Matthew McKown – Conservation Metrics; Patrick Jodice – USGS South Carolina Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit, Clemson University; George Wallace – American Bird Conservancy; Jennifer Wheeler – BirdsCaribbean

Other talks that were about or mentioned Caribbean birds:

Unifying the Voice for Migratory Bird Conservation Across the Western Hemisphere through Festivals. Bonfield, S. Environment for the Americas.

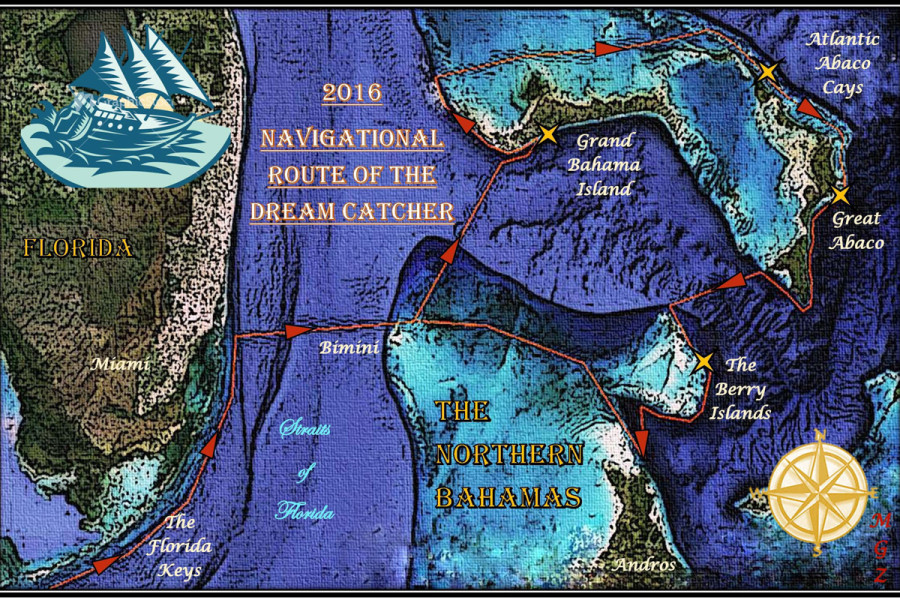

Advancing Caribbean Bird Conservation through the Media. Sorenson, Lisa – BirdsCaribbean; Leo Douglas – BirdsCaribbean; Scott Johnson – Bahamas National Trust/ BirdsCaribbean

How does a two-day bird education event affect the long-term knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of high school students? Evidence from 13 Jamaican high schools. Douglas, Leo – BirdsCaribbean; Luke Powell – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Lisa Sorenson – BirdsCaribbean; Loraine Cook – Dept of Education, University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica; Susan Bonfield – Environment for the Americas; Peter Marra – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

Seabird Colony Decline, Nesting Performance, Human Harvest, and Invasive Predators in the Southern Grenadine Islands. Smart, Wayne – Arkansas State University; Natalia Collier – Environmental Protection in the Caribbean; Virginie Rolland – Arkansas State University

Interspecific competition between resident and wintering warblers: Evidence from a 3D removal experiment. Powell, Luke – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Elizabeth Ames – The Ohio State University; James Wright – The Ohio State University; Nathan Cooper – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Peter Marra – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

A snapshot of the movements of White-crowned Pigeons satellite-tracked in Florida and the Caribbean. Kent, Gina – Avian Research and Conservation Institute (ARCI); Ken Meyer – Avian Research and Conservation Institute; Ricardo Miller – Jamaica National Environment and Planning Agency; Alexis Martinez – Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources; Predensa Moore – Bahamas National Trust; Paul Watler – National Trust for the Cayman Islands

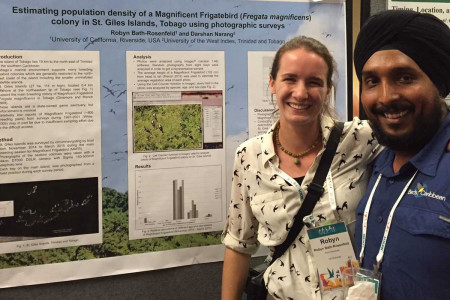

Estimating population density of a Magnificent Frigatebird (Fregata magnificens) colony in St. Giles Islands, Tobago using photographic surveys. Bath-Rosenfeld, Robyn – University of the West Indies/UC Riverside; Darshan Narang – University of the West Indies, Trinidad & Tobago

Conservation Biology of the Critically Endangered Bahama Oriole: Estimating Current Population Size and Evaluating Threats. Omland, Kevin – University of Maryland, Baltimore County; Shelley Cant – Bahamas National Trust; Scott Johnson – Bahamas National Trust/ BirdsCaribbean; Matthew Jeffery – Audubon; John Tschirky – American Bird Conservancy; Holly Robertson – American Bird Conservancy; Melissa Price – University of Hawaii at Mānoa; Scott Sillett – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center.

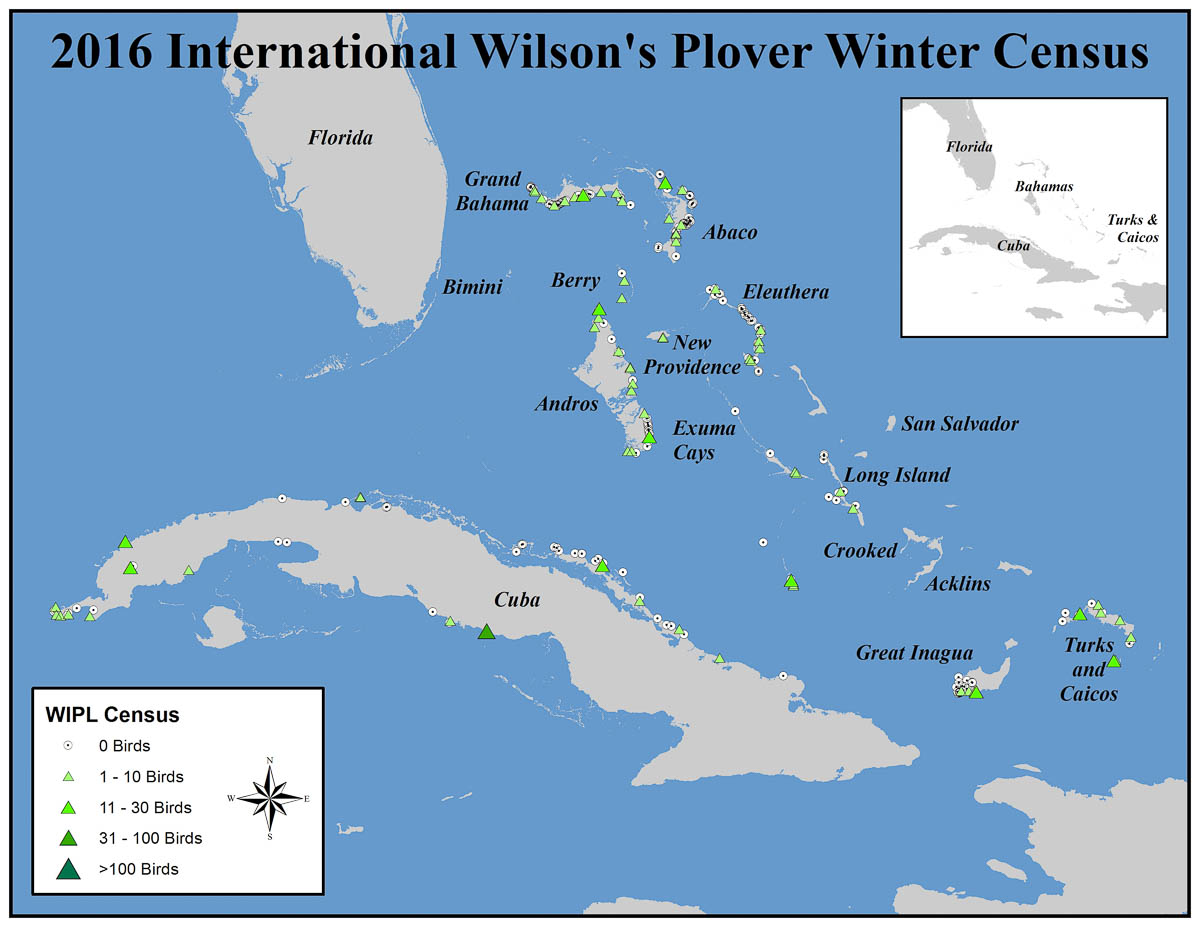

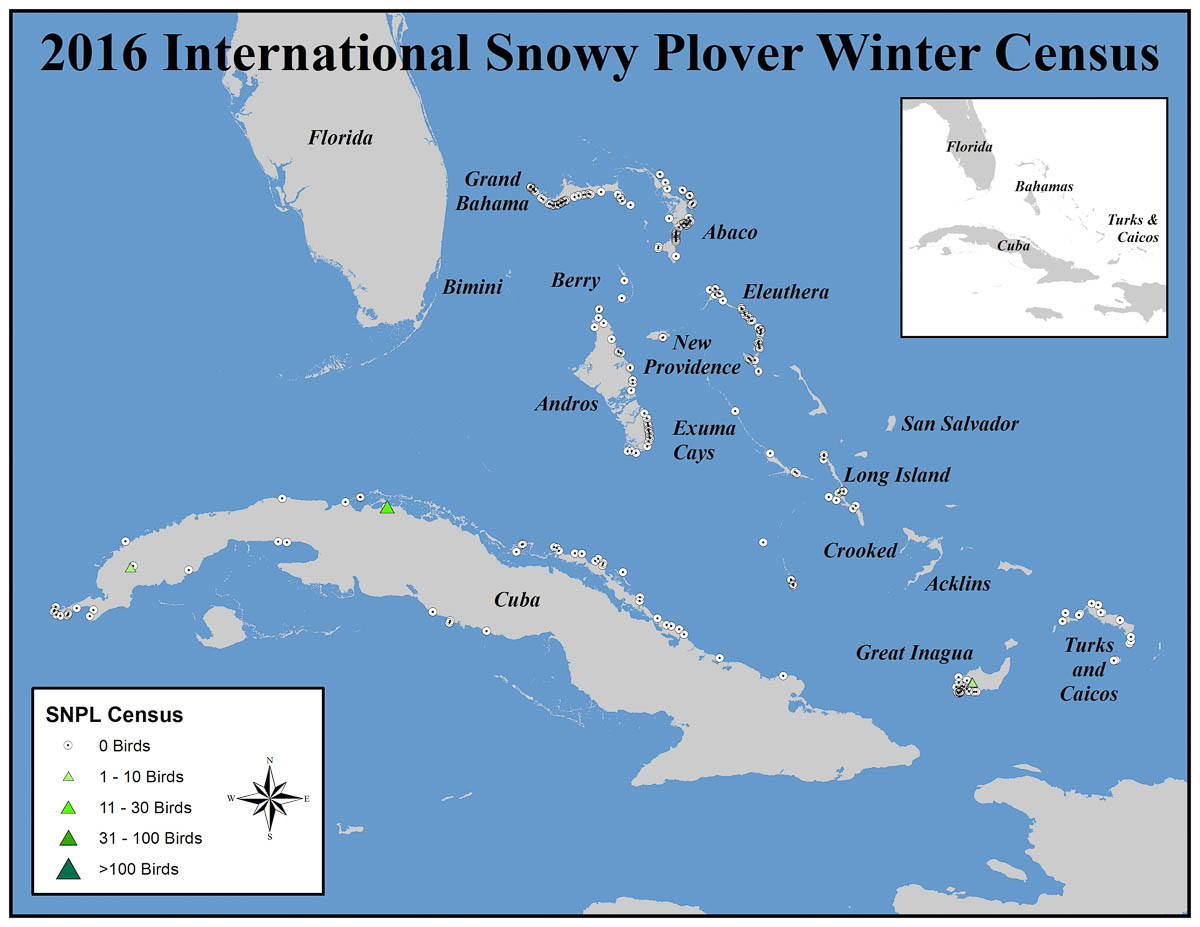

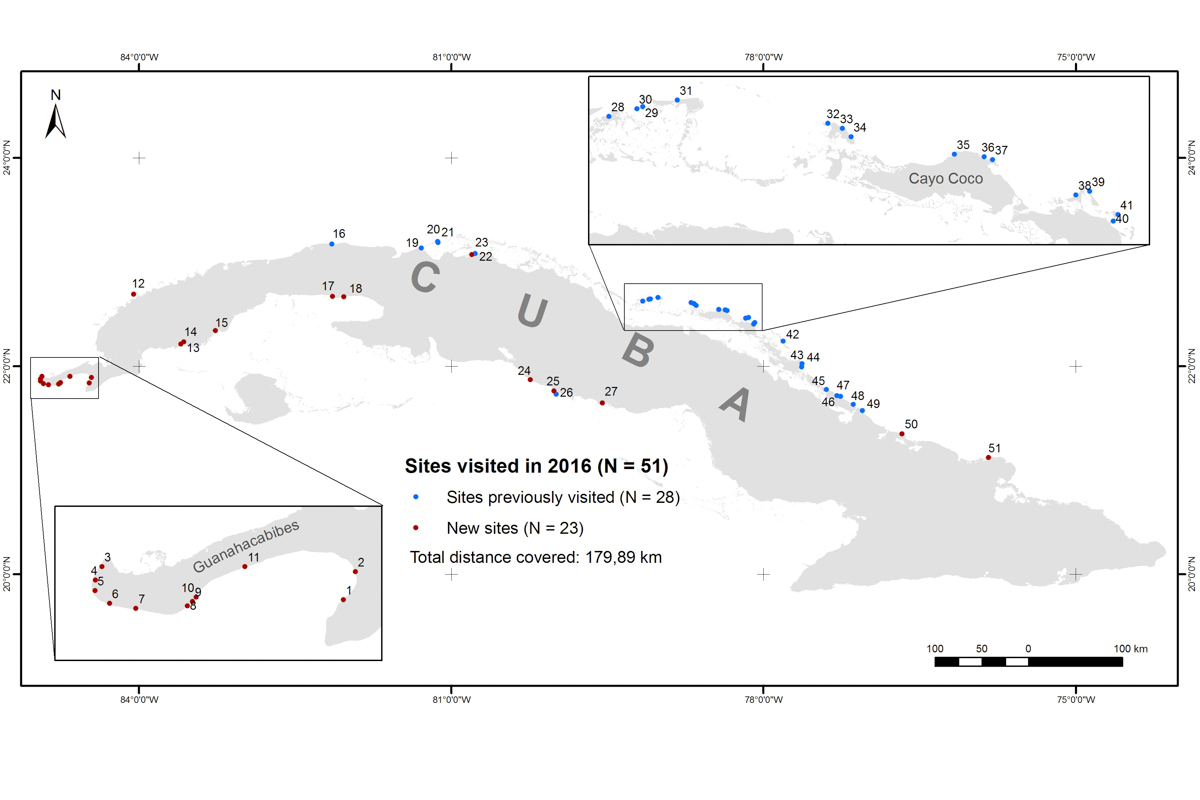

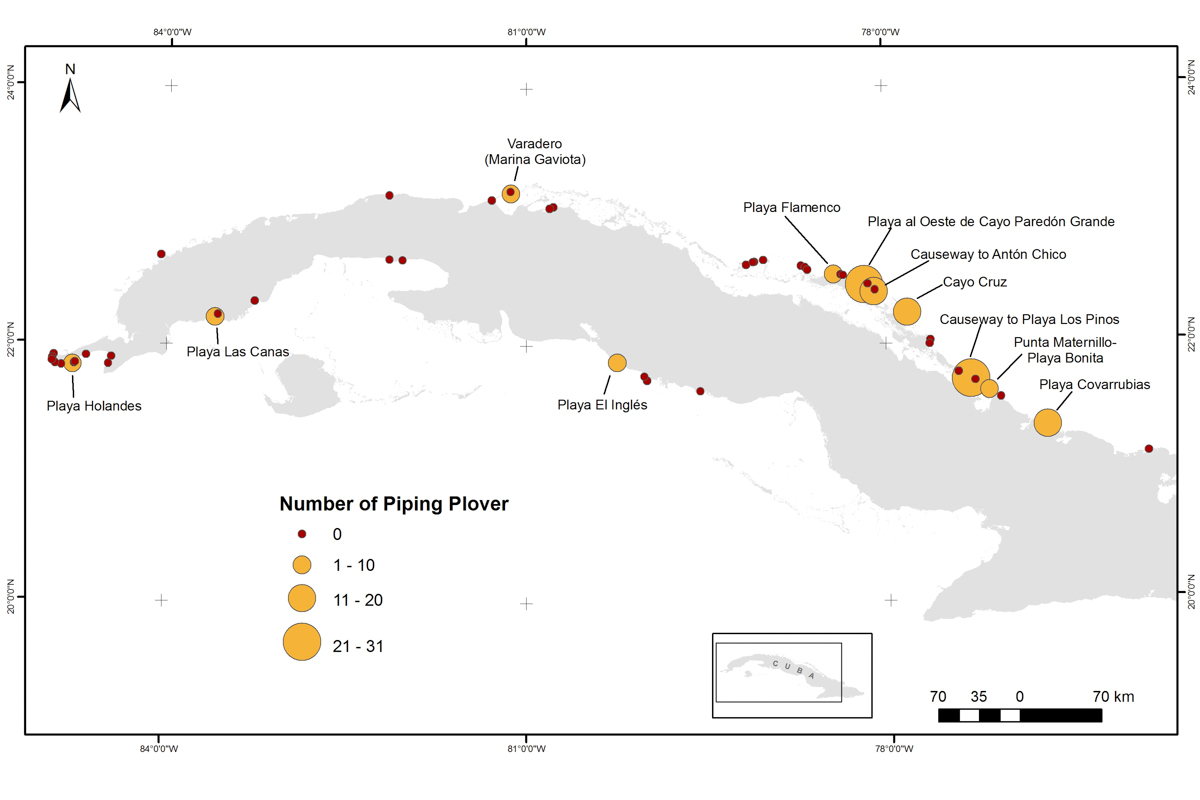

Advances in the Study and Conservation of Waterbirds and Shorebirds in Cuba. Jiménez, Ariam, University of Havana, Cuba.

Population biology, life history, ecology, and conservation of the endangered Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis). Wilson, Maya – Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; Jeffrey Walters – Virginia Tech

Pelicanus occidentalis’ nesting disturbance on a small island in the Guadeloupe archipelago. Priam, Judith – Servicios Cientificos y Tecnicos

Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush: outcomes and next actions in both breeding and wintering grounds. Lloyd, John – Vermont Center for Ecostudies; Eduardo Inigo-Elias – Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Kent McFarland – Vermont Center for Ecostudies; Christopher Rimmer – Vermont Center for Ecostudies; Juan Carlos Martinez-Sanchez – Vermont Center for Ecostudies; Yves Aubry – Environment and Climate change Canada

Narrowing the Search for Overwintering Bicknell’s Thrush in the Caribbean. Rimmer, Christopher – Vermont Center for Ecostudies; John Lloyd – Vermont Center for Ecostudies; Jose Salguero – Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources

Sustainability Assessment of Plain Pigeons (Patagioenas inornata wetmorei) Illegally Hunted in Puerto Rico. Rivera-Milán, Frank – United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Branch of Population and Habitat Assessments

Management and conservation of cavity nesting birds in Monte Cabaniguan Wildlife Refuge, Las Tunas, Cuba. Rodríguez, Aryamne Serrano

Cuban Bird diversity and habitat conservation through the Cuban National System of Protected Areas (SNAP). Mugica, Susana

Genetic characterization of Cuban colonies of American flamingos: impacts on its management and conservation. Quevedo, Alexander Llanes – University of Havana, Cuba; Roberto Frías Soler – University of Heidelberg, Germany; Georgina Espinosa López – University of Havana, Cuba

Bird migration across western Cuba. Hernández, Alina Perez

What a permanent banding monitoring scheme tell us about migration, territoriality and effects of hurricanes on birds of tropical dry forests of southeastern Cuba. Segovia Vega, Yasit

The current and future effects of climatic variation and change on tropical Frugivores. Boyle, Alice – Kansas State University

Seasonal changes in habitat utilization of Swainson’s Warblers in response to moisture and prey abundance. Brunner, Alicia – The Ohio State University; Christopher Tonra – The Ohio State University

Where and for how long do migrating landbirds stopover along the northern Gulf of Mexico? A radar perspective. Buler, Jeffrey – University of Delaware; Matthew Boone – University of Delaware; Jill LaFleur – University of Southern Mississippi; Frank Moore – University of Southern Mississippi; Timothy Schreckengost – University of Delaware; Jaclyn Smolinsky – University of Delaware

Assessing Plasticity in the Migratory Behavior of a Songbird Wintering in the Caribbean Using the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. Dossman, Bryant – Cornell University; Colin Studds – University of Maryland, Baltimore County; Peter Marra – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Amanda Rodewald – Cornell University

Recovery of Birds Under the Endangered Species Act. Greenwald, Noah – Center for Biological Diversity; Kieran Suckling – Center for Biological Diversity; Ryan Beam – Center for Biological Diversity; Loyal Mehrhoff – Center for Biological Diversity; Brett Hartl – Center for Biological Diversity

Constructing a range-wide migratory network in an aerial insectivore to assess which seasons drive long-term changes in abundance. Knight, Samantha – University of Guelph; David Bradley – Bird Studies Canada; Robert Clark – Environment and Climate Change Canada; Marc Bélisle – Université de Sherbrooke; Lisha Berzins – University of Northern British Columbia; Tricia Blake – Alaska Songbird Institute; Eli Bridge – Oklahoma Biological Survey; Russell D. Dawson – University of Northern British Columbia; Peter Dunn – University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Dany Garant – Université de Sherbrooke; Geoff Holroyd – Beaverhill Bird Observatory; Andrew Horn – Dalhousie University; David Hussell – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources; Olga Lansdorp – Simon Fraser University; Andrew Laughlin – University of North Carolina Asheville; Marty Leonard – Dalhousie University; Fanie Pelletier – Université de Sherbrooke; Dave Shutler – Acadia University; Lynn Siefferman – Appalachian State University; Caz Taylor – Tulane University; Helen Trefry – Beaverhill Bird Observatory; Carol Vleck – Iowa State University; David Vleck – Iowa State University; Linda Whittingham – University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; David Winkler – Cornell University; D. Ryan Norris – University of Guelph

Tri-trophic ecology of native nest flies (Philornis trinitensis) in grassquits and mockingbirds of Tobago. Knutie, Sarah – University of South Florida; Jordan Herman – University of Utah; Jeb Owen – Washington State University; Dale Clayton – University of Utah

Prioritizing and implementing projects for the rarest bird species in the Americas. Lebbin, Daniel – American Bird Conservancy

Autumn migration ecology and biogeography of Red Knots at the Altamaha River Delta, Georgia, USA. Lyons, James – USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; Tim Keyes – Georgia DNR; Bradford Winn – Manomet; Kevin Kalasz – Delaware DFW

A Place to Land: Stopover Ecology and Conservation of Migratory Songbirds. Moore, Frank – University of Southern Mississippi; Emily Cohen – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Jeffrey Buler – University of Delaware

Phylogenomic analysis using ultraconserved elements reveals cryptic diversity in the complex Neotropical genus Pachyramphus. Musher, Lukas – American Museum of Natural History; Joel Cracraft – Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History

Abundance and body condition of a Neotropical migratory bird overwintering in mangrove forests in Colombia. Reese, Jessie – Virginia Commonwealth University; Lesley Bulluck – Virginia Commonwealth University

Examining dietary overlap in resident and wintering migratory warblers using next generation metabarcoding of feces. Welch, Andreanna – Durham University; Luke Powell – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Peter Marra – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center; Robert Fleischer – Smithsonian Institution

The Population Genetic Structure of the Red-Billed Tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) in the Gulf of California, México. Piña-Ortiz, Alberto – Centro de Investigaciónen Alimentación y Desarrollo, A.C. Unidad Mazatlán; Luis Enriquez-Paredes – Facultad de Ciencias Marinas – Universidad Autónoma de Baja California; José Castillo- Guerrero – Centro Universitario de la Costa Sur, Universidad de Guadalajara.; Albert van der Heiden – Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A.C. Unidad Mazatlán

![An artist's rendition of the Semper's Warbler (Joseph Smit [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://www.birdscaribbean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Sempers-Warbler-LeucopezaSemperiSmit-450x300.jpg)