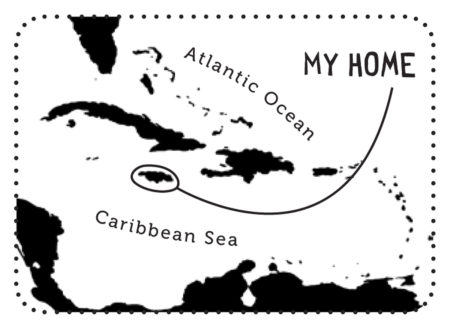

A local community that understands the value of natural habitats and the wildlife that lives there is key to successful long-term conservation. Find out how this happens from Kristy Shortte, a Program Officer at the NGO ‘Sustainable Grenadines,’ on Union Island in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. From building observation platforms at vital wetlands, to garbage clean-ups and installing information signs, to training locals to identify and help monitor birds, Kristy describes the amazing and inspiring range of work carried out by her organization, local partners – and of course, the local community!

At the trans-boundary NGO Sustainable Grenadines Inc (SusGren) we know that conserving the places where birds live is key to their survival. But how do we achieve this? So many of our habitats are under threat—from pollution and degradation by human activities, to outright destruction for development. When there are competing demands on the use of our natural resources, we need to make wise decisions. Sometimes we need to educate our local citizens about the immense value of these areas to people and wildlife, and to get them actively involved in their conservation. It’s a hands-on approach with community partners. Showing people the benefits of managing and protecting habitats is the best way to ensure the long-term health of bird populations and the habitats on which they depend.

Finding the best ways to protect birds and their habitats

Here at SusGren, we have taken the initiative to support birds and protect the places they live through two projects – both completed during the pandemic of 2020! SusGren believes that some areas are so special that they need to be protected – no ifs, ands, or buts!!!!

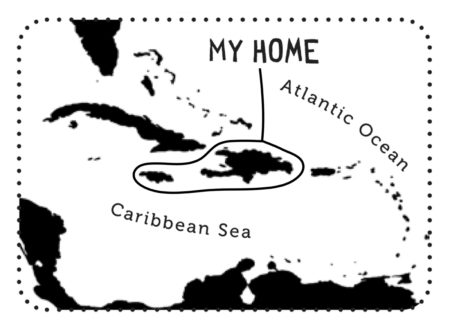

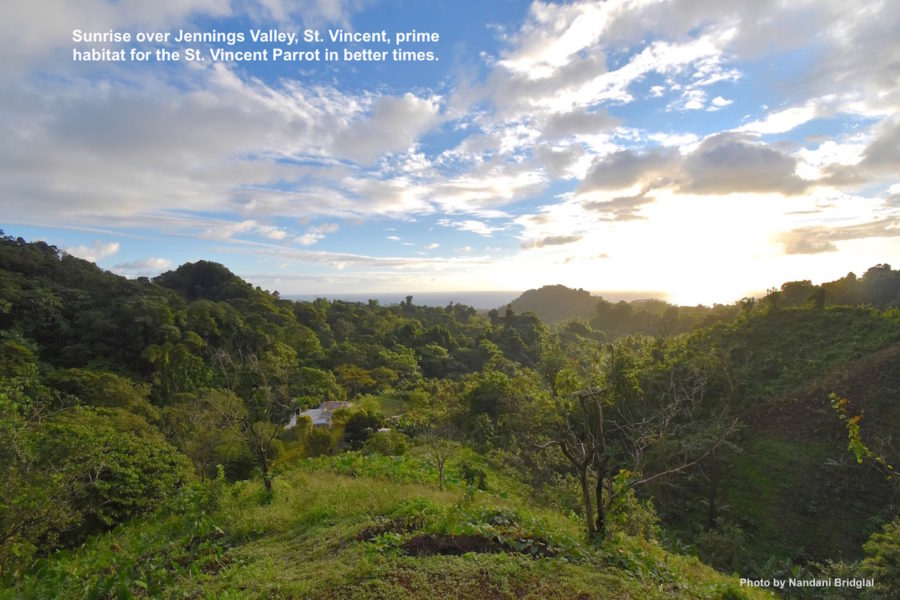

After many years of hard work to restore Ashton Lagoon and develop it as a bird and nature sanctuary for enjoyment by all, we turned our attention to Belmont Salt Pond. This is the second largest ecosystem on the island of Union and one of the last two remaining salt ponds in the entire St. Vincent and the Grenadines (he other salt pond is on Mayreau). Salt picking is still practiced at Belmont, providing economic benefits to locals.

So…what’s so special about Belmont Salt Pond?

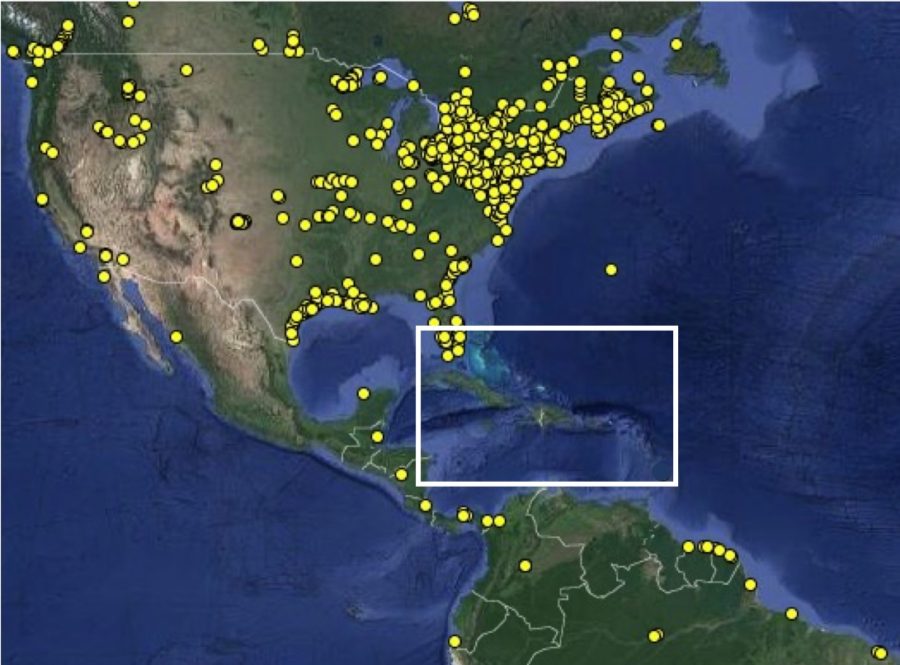

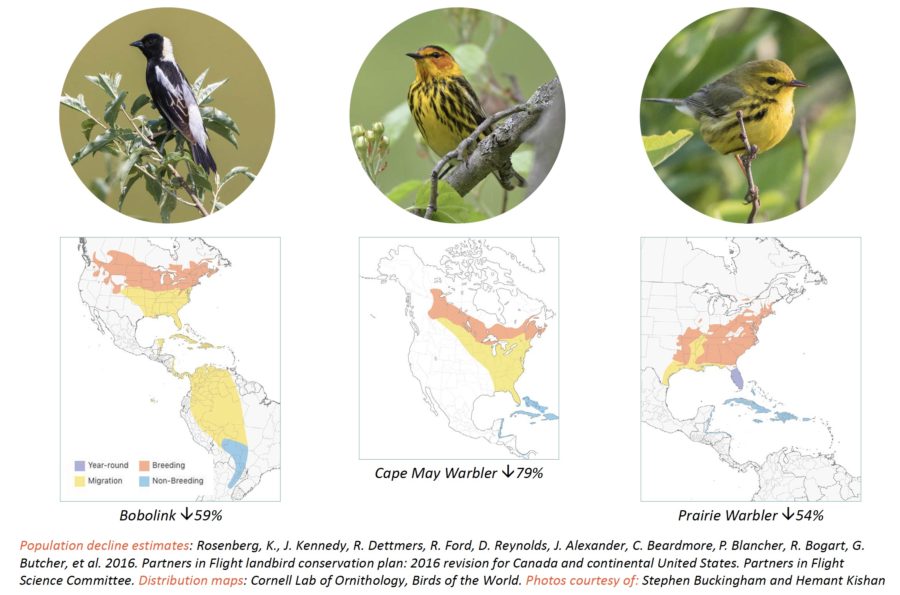

The Belmont Salt Pond area is significant, in that it provides habitat to many species of resident and migratory birds. Here you can see Whimbrels, Willets, Blue-winged Teal, Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs, Mangrove Cuckoo, and even the American Flamingo on occasion. Migratory birds use Belmont as a place to rest and feed. This can be for a few days or weeks, before they continue with their migration, while others stay from fall to spring. For other birds, the Salt Pond is ‘home’ all year round.

With this rich history and biodiversity and the salt pond threatened by human activities, SusGren decided to enhance the area for enjoyment by locals and visitors alike. This would help ensure the protection of the area’s biodiversity and would increase ecotourism opportunities in Union Island, following our successful restoration of nearby Ashton Lagoon 2 years ago. The platform would also help us to continue the long-term bird monitoring of our wetlands through participation in the Caribbean Waterbird Census.

Taking a community-based approach

Due to a lack of community knowledge of the importance of the area, it was being used for the burning of charcoal and dumping garbage. We knew that over time these activities would damage Belmont Salt Pond and biodiversity would be negatively impacted. So at Susgren we decided to carry out a project in partnership with members of the community, to ensure that such behavior is reduced and eventually eliminated.

As part of this approach, SusGren contributed towards a cleanup organized by a local group of 10 people called “Union Island Cleanup Squad.” They held massive cleaning up sessions at the Belmont Salt Pond on May 7th and May 13th, 2020. A total of 30 bags of trash was collected during the first session, and 40 additional bags of trash were picked up at the second cleanup around the edges of the pond. It was great to see local community groups actively taking up the stewardship mantle of their island!

Follow the signs!

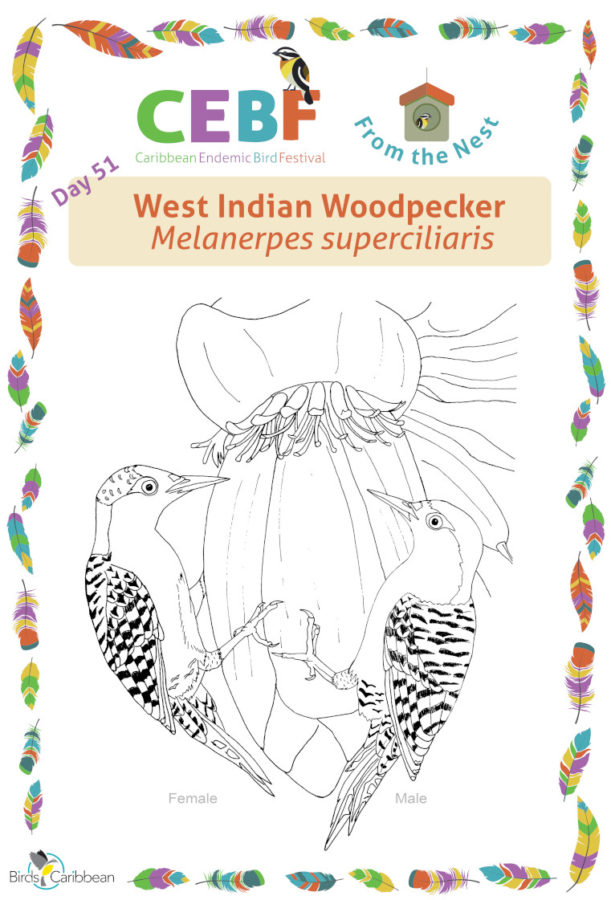

Our project also involved the construction of viewing platforms at Belmont Salt Pond, designed to provide people with a fantastic overview of the wetland and the birds living there. At each of the Belmont Salt Pond platforms – and at the Ashton Lagoon Eco Trail – we installed interpretive signs displaying resident and migratory birds. We worked with BirdsCaribbean to design signs that included land birds, wetland birds, and shorebirds likely to be seen at each of the sites. At Ashton Lagoon, one sign also provides visitors with knowledge about the marine and terrestrial species of animals found in the area.

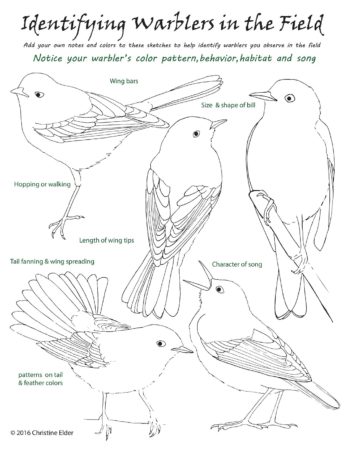

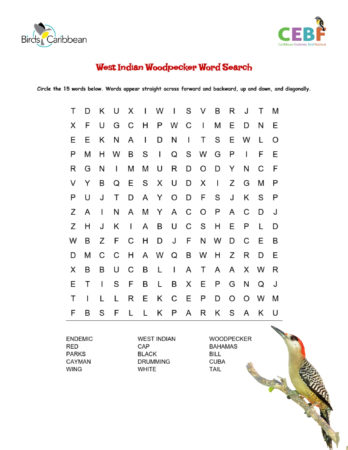

Our interpretive signs include features on bird identification. Thus, someone using the platforms at Belmont Salt Pond or our bird towers at Ashton Lagoon can receive a “self-crash-course” in basic bird identification. Moreover, there are now three 4 x 6 billboard signs installed at Belmont Salt Pond that explain the history of the area and its cultural and environmental importance. Two ‘rules’ signs also notify visitors about appropriate behavior in the area.

Keeping the trash at bay

To reduce the problem of litter, we installed attractive garbage receptacles at both Belmont Salt Pond and Ashton Lagoon. The bright green receptacles are adorned with images of the various birds one can see in the area. Our hope is that this will help build local pride and community ownership and encourage people to dispose of their garbage in a responsible way.

Since the installation of 4 bins at each location, we are gratified to see that people are using them. The local solid waste management company ‘’Uni Clean’ assists with the weekly disposal of trash from these areas.

Reaching out in different ways

We found different ways of reaching out to our stakeholders and the general public. Normally, we would have been hosting lots of in-person outreach and birding activities and events with the community and schools during the last year. But due to the pandemic and schools closing, we used radio and social media platforms to engage the community and key stakeholders. We made phone calls and delivered letters with updates on our projects. We also sent out a media blast with the local telecommunications company on the island, so that recipients could obtain a poster of the activities being undertaken at Belmont Salt Pond on their phones.

Finally, we had a hugely successful radio interview and webinar with the show, “Conversation Tree” on Radio Grenadines. SusGren’s Program Director, Orisha Joseph and I gave a presentation and discussed our activities with the radio host. This was seen by over 2,000 people and was very well-received.

World Shorebirds Day

To further community involvement in our work and help people develop a love for the environment and birds, we collaborated with Katrina Collins-Coy, Union Island Environmental Attackers, and celebrated World Shorebirds Day in September, 2020. Eleven students and two teachers from the Stephanie Browne Primary School participated.

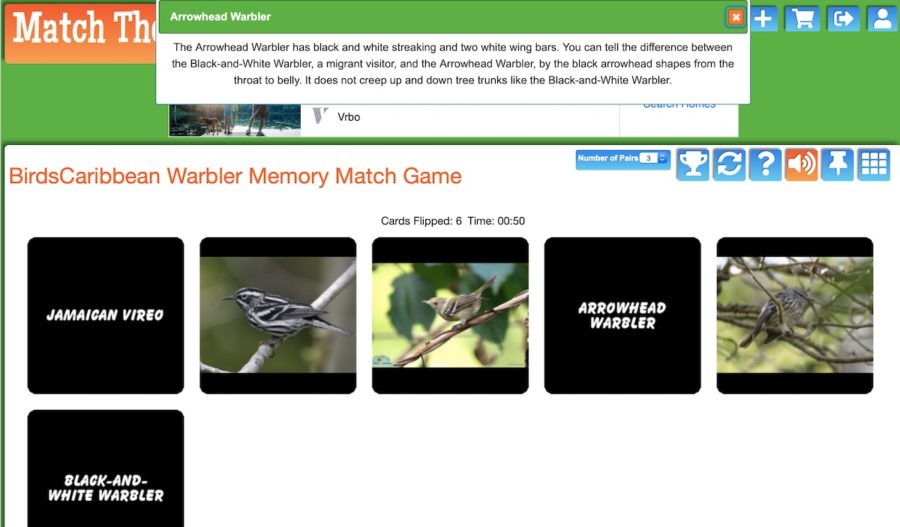

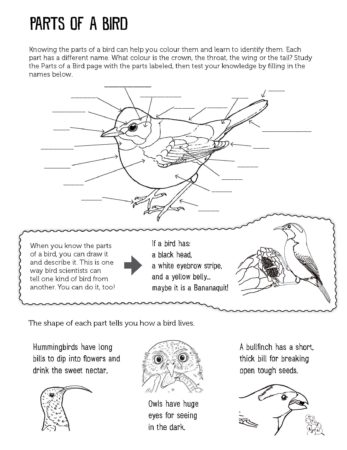

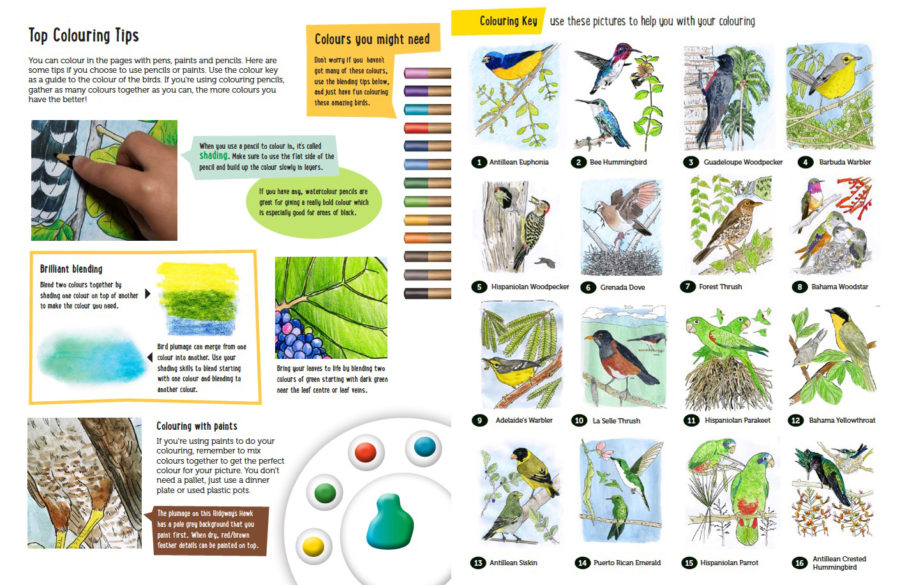

The celebration involved a birding walk with Bird Bingo and a Bird Identification tour along the Ashton Lagoon Trail. The children also enjoyed activities in the classroom, such as learning about the Parts of a Bird, bird games, and bird arts and crafts. We were elated to see the enthusiastic students and teachers come out as early as 5:30 am to be a part of the session!

Birds of Belmont Salt Pond – A New Resource!

Through this project (with matched funding from the SVG Conservation Fund) we also developed a booklet entitled “Birds of Belmont Salt Pond.” The booklet includes notes from SusGren’s directors, information on the project’s team, a brief history of the Belmont Salt Pond, photographs of resident and migratory birds found there, and a full checklist and space for taking notes while bird watching and monitoring. Thirty copies were printed and distributed to key stakeholders in the community and other organizations in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. We hope this will be a great resource for visitors.

Bird Identification Training Workshop—“Conserving Caribbean Shorebirds and their Habitats”

We weren’t finished yet! We also held a five-day bird identification training workshop as part of the project, during October 2020. The workshop was facilitated by Lystra Culzac, who is the Founder and Manager of Science Initiative for Environmental Conservation and Education (SCIENCE) and graduate of our Conserving Caribbean Shorebirds and their Habitats Training Workshop in 2019 (as is Kristy!). Those taking part represented a wide range of professions, from Park Rangers, Tourism Division, Environmental Groups, and regular community members. As part of the training, a bird monitoring trip took place at the newly installed platforms, making good use of our new booklet “Birds of Belmont Salt Pond.”

We included training in seabird monitoring as part of the workshop and participants took a trip to Catholic Island and Tobago Cays Marine Park. Here they got the opportunity to learn firsthand how to identify a wider variety of the seabird species in their natural habitats. Following the bird watching trip in the Tobago Cays, SusGren, in partnership with SCIENCE, collaborated on a clean-up effort at Petit Bateau, one of the cays in the Marine Park and a known seabird habitat. A total of 6 bags of trash was collected.

Continued CWC Monitoring

At both Ashton Lagoon and Belmont Salt Pond we have been carrying out Caribbean Waterbird Census (CWC) surveys for many years. These surveys help us to keep track of which birds are using these sites, while keeping an eye out for any changes or threats to the habitats. During the project we carried out 9 CWC surveys across Ashton Lagoon and Belmont Salt Pond, making visits twice a month. Now that the project is over we plan to continue to monitor the birds at both sites using CWC surveys. With all our newly trained birders on Union island, equipped with binoculars and copies of the ‘Birds of Belmont Salt Point,’ we should have plenty of support to do this!

How did the community respond to our work?

During an Attitude and Perception survey interview done with residents on the island, persons expressed excitement and satisfaction with the new development. One noted interviewee was Benjamin Wilson, a Tobago Cays Park Ranger. Wilson said, “Before the enhancement, I would have passed the salt pond straight – but now I have to gaze at the work that was done.’’ SusGren believes that this project was the first step towards having a local community that value ‘their’ wetland. The wildlife viewing platform is now being regularly used by locals and tourists alike!

Mission accomplished? Yes, for that phase, which is a first step in the right direction towards bird and habitat conservation.

This project was made possible with funding and support from BirdsCaribbean via the US Fish and Wildlife Service NMBCA program and BirdsCaribbean members and donors, with matching funds from the SVG Conservation Fund.

Kristy Shortte has worked with Sustainable Grenadines Inc since 2013, starting out as an Administrative and Research Assistant. Since 2017 she has served as a Program Officer. Kristy has qualifications in Business Studies, and since working at Sustainable Grenadines, she has been dedicated to using her business knowledge and environmental training and experience to empower her community in the Grenadines to protect and develop their resources sustainably. She has grown to love and be inspired by nature and birds since working for SusGren. She comments, “A lot of times I would look at birds and observe how they are so fearless and free in the sky and by looking at these creatures you learn from them about how to create a beautiful life.”