We are pleased and proud to announce that Inauguration Day, 20th January 2021 was the start of a new and wonderful initiative. This big event happened far from Washington D.C., in a remote wetland near Negril, Jamaica. On this day, two West Indian Whistling-Ducks, nicknamed “Joe” and “Kamala”, became the first of their kind to bear GPS trackers. From now on, like their namesakes, these birds will be the focus of constant scrutiny and international attention. Their solar–powered backpack trackers will report their locations every hour. Read on as Dr. Ann Haynes-Sutton shares more with us about this exciting new initiative.

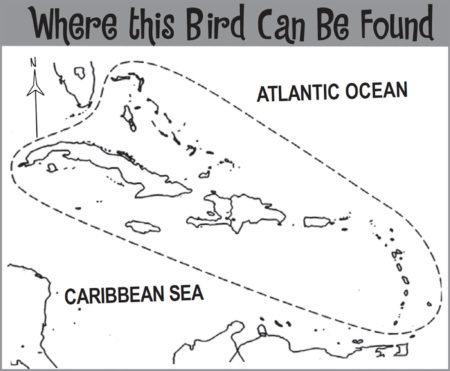

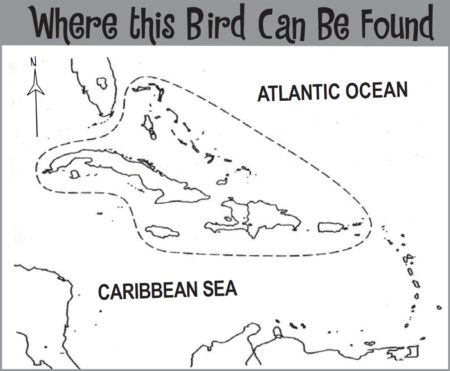

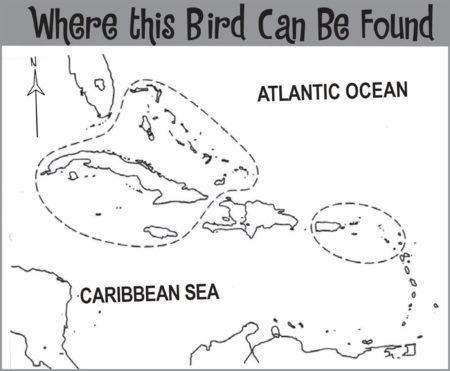

West Indian Whistling-Ducks (WIWD) are one of the rarest ducks in the Americas. We know very little about the behavior and movements of these secretive ducks, which are found only in the northern Caribbean (including the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos Islands, Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico, Antigua and Barbuda; extirpated, very rare, or vagrant elsewhere). WIWDs are classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as “Near Threatened.” Threats to these ducks include destruction of their wetland habitats, climate change (severe droughts, storms, and flooding), predation by invasive species (e.g., mongoose), poaching, and pollution from agriculture and other sources. BirdsCaribbean members have long reported declines in the population of Whistling-Ducks and their habitats throughout their range, which led to the creation of the WIWD and Wetlands Conservation Project. Jamaican populations are among the worst affected in recent years.

About 10 years ago, I regularly saw more than 150 in the Negril wetlands but over the years I heard reports that their numbers had declined catastrophically. The reports reached the Jamaican Government, who made the recovery of the WIWD the focus of part of their Global Environment Facility Project “Integrating Water, Land and Ecosystems Management in Caribbean Small Island States – Jamaica sub-project Biodiversity Mainstreaming in Coastal Landscapes within the Negril Environmental Protection Area of Jamaica.” The Government hired me as the lead expert for the West Indian Whistling-Duck component.

In order to plan for the ducks’ recovery, I needed detailed information, for example, how many there are, where they feed, nest, and roost, and the threats they face. I couldn’t find any such data, for Negril or any other part of Jamaica. I set out to survey the ducks from the ground, from roads, and by boat, using tapes, drones and cameras. All these approaches failed. Apart from one location, I could not find any ducks, although with the help of the Negril Environmental Protection Trust I received some reports from local community members.

Thus, I was more than delighted when BirdsCaribbean and Hope Zoo Preservation Foundation supported the purchase and importation of some GPS trackers from Cellular Tracking Technologies. These state-of-the-art trackers, used successfully on species like Peregrine Falcons and Greater Sage Grouse, will plot the positions of the ducks every hour to within a few metres.

BirdsCaribbean Executive Director, Lisa Sorenson commented, “We are thrilled with the launch of this exciting project. I expect it will lead to major improvements in our knowledge of the ducks’ movements and habitat use. If so, BirdsCaribbean will seek to do tracking in other parts of the Caribbean. WIWDs populations are small on every island where they occur (with the exception perhaps of Cuba) and they have been extirpated from several countries. We hope to ramp up our knowledge and conservation of this important regional endemic.”

On 20th January 2021, our small team – composed of Ricardo Miller of the National Environment and Planning Agency, D. Brandon Hay of the Caribbean Coastal Area Management Foundation, and myself – captured two West Indian Whistling-Ducks in Negril and fitted them with transmitters. It was an amazing thrill to hold these beautiful birds in our hands and very carefully attach the devices. Gina Kent from the Avian Research and Conservation Institute in Florida and Lisa Sorenson of BirdsCaribbean were on hand remotely to provide us with technical advice and support.

With excitement and trepidation we set the ducks free. Now we are looking forward to see what we can learn from them. The information I gather will support my work with the local and international communities to develop and implement measures to preserve West Indian Whistling-Ducks in Negril. No doubt our findings will promote initiatives to assess and conserve the ducks in the rest of Jamaica, and throughout their range.

We decided to call the ducks “Joe” and “Kamala” in honour of the very auspicious date and our hope that they can help to save the species. Go for it Kamala and Joe – we wish you well!

Dr. Ann Haynes-Sutton is a Conservation Ecologist and Co-Chair of BirdsCaribbean’s Bird Monitoring Working Group and Seabird Working Group. She has been a long-time member of BirdsCaribbean’s WIWD Working Group and is also the senior author of Wondrous West Indian Wetlands: Teachers’ Resource Book, published by BirdsCaribbean and used in over 145 Wetlands Education Training Workshops since 2002.

Acknowledgements: We are thankful to BirdsCaribbean members and donors whose financial support made this project possible. We are also thankful to National Environment and Planning Agency, Caribbean Coastal Area Management Foundation, Avian Research and Conservation Institute, Hope Zoo Preservation Foundation, and Cellular Tracking Technologies for support and assistance with this exciting project.

If you would like to donate to support this project, please click here. Thank you in advance!