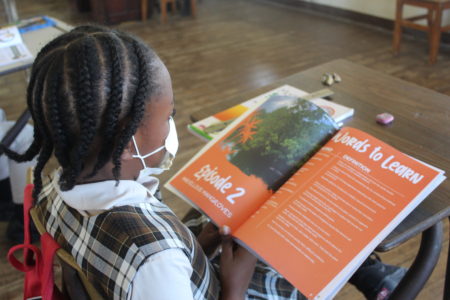

Daniela Ventura, a Cuban student and dedicated ornithologist, describes her impressions and experiences at BirdsCaribbean’s first Landbird Monitoring Workshop in the Dominican Republic this past February.

“What do you do for a living?” is among the top-ten questions you will be asked throughout your life, whether it comes from a stranger—like the immigration officer at the airport—or from close friends and even family. “I am an ornithologist,” is a tricky answer because, for most people, counting birds may not sound like a real job. In these situations, where you’re often met with a blank stare or a judging look, it’s best to respond with your sweetest smile – knowing that few people understand the complexity of the skills needed for proper bird identification in the wild. In the case of close friends and family, you can invite them on a field trip to become an “ornithologist” for one day. Then, you’ll only need to sit back and enjoy watching their eyes, as they are mesmerized trying to figure out and make some sense of so many shapes, colors, sounds, and behaviors.

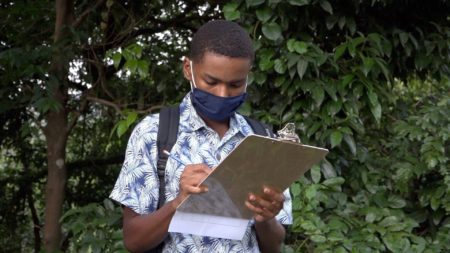

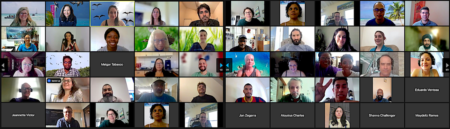

Counting birds is not easy. And even less so if you’re trying to do it scientifically and methodically, to make a real impact on our understanding of bird population dynamics and aid in conservation. This was the purpose of my trip to the Dominican Republic from February 16th-20th, 2022 – to attend the first Caribbean Landbird Monitoring Training Workshop. Bird lovers and conservationists from across the Caribbean gathered at the beautiful town of Jarabacoa to learn from experts how to count and monitor birds more efficiently and meaningfully. I consider myself lucky to have participated in this life-changing experience. In this blog, I will try to do this incredible training justice and translate into words the whirlwind of emotions, feelings, and events that come to my mind, when I recall those memorable and intense days. This is the account of “La Cubanita,” as the charming and welcoming Dominicans called me.

Adventure Awaits

My first memory of the Dominican Republic is dream-like. A foamy sea of golden clouds, tinged with orange and pink reflections, dotted at intervals by green-crowned mountains and river beds. Just as the sun was setting and the early stars appeared in the sky, I beheld the first lights of Santo Domingo. My heart was pumping fast. I couldn’t be happier. As a Cuban, I carry with me the Caribbean pride in my blood and soul. This, my first trip abroad, was taking me into the home of a sister island. I was ready to dive in and immerse myself with all my senses. I knew this would be a defining professional and personal experience.

What quirky turn of the road brought me here? I must say, I’ve found that the best things in life are the result of a perfect balance between perseverance and mere chance. Instead of worrying too much and asking oneself unhelpful questions like, “do I deserve this?” it’s better to be thankful, make the most of every opportunity, and be ready to do the same for others.

Santo Domingo lights to misty Jarabacoa mountains

A giant mural greets visitors upon arrival at the International Airport: “Las noches de Santo Domingo” (The nights of Santo Domingo). The welcome couldn’t have been more precise. My first contact with the city happened at dusk. I barely had time to make sense of the blurry city lights before the taxi hired to take me to the central mountains of the Dominican Republic whisked me away towards my destination. Three hours later, I arrived in Jarabacoa, “the land of waters,” named by the original inhabitants of the island. This name was also just right, as I was greeted by a cold drizzle and the humid air coming through my lungs. When I disembarked the taxi at Rancho Baiguate, almost everyone had already gone to bed. All but Maya Wilson, the tireless workshop organizer, who kindly welcomed me with a belated dinner, and my first taste of Dominican cuisine. For my hungry tummy, it felt like a kiss from home.

Maria Paulino and Ivan Mota, the local trainers, were also up late making the last arrangements for their early morning presentations. Maria’s big and warm smile swept away all the cold of the Jarabacoa night. This was the first time I experienced the world-famous hospitality and friendliness of the Dominican people. Over the next few days, I would have the huge privilege of enjoying such generosity on countless occasions.

The sound of the forest

I woke up very early the next morning. There was no use wasting time in bed, while there were so many things to see and learn. I dressed quickly, grabbed my binoculars, and stepped out of my room to greet the cloudy forest. It was cold outside, the leaves were heavy with dew. I took a few steps, and then it dawned on me – the forest looked familiar but SOUNDED so different. I was not able to recognize even one bird song. Even the common and widespread Red-legged Thrushes were speaking a totally distinct language. It felt so bizarre. Cuba and the Dominican Republic, both so close, and yet our shared birds were almost acting like different species. I had so much to see, and so much to learn. Still dazed by the discovery, I headed towards the conference facilities with my mind filled with expectations.

Caribbean waves

The workshop had one major goal: to train participants in the use of the PROALAS protocol – a standardized set of survey methods for monitoring birds, specially designed for tropical habitats. Identifying birds in a Caribbean or Latin American rainforest can prove a hard pill to swallow for even the most experienced birder. But, before diving into the more difficult topics of the workshop, we had a lovely welcome session. The fantastic organizers, Maya Wilson, Holly Garrod, and Jeff Gerbracht did their best to make us feel at ease from the beginning.

Their jobs were made easier by two important elements. First, we were situated in the incredibly beautiful setting at Rancho Baiguate. We had the conference sessions at an outdoor facility next to the Rancho’s pool, and a few steps away from the Baiguate river and the cloud forest. It was easy to get distracted by the noisy Bananaquits and the purple shine of the Antillean Mangos.

During the first break, I skipped coffee and ran to the nearby trees to try my luck on lifers. I was extremely fortunate that the first bird I glimpsed was the stunning Black-crowned Palm Tanager, a Hispaniolan endemic! The bird kindly allowed me to enjoy its beautiful green-olive feathers and the black crown spotted with white that makes it look as if it has four eyes (“cuatrojos” in Spanish). I could have spent all day contemplating this fascinating bird, but a call from the conference room brought me back to reality. We had some PROALAS to learn.

The second thing that made us feel at home from the start was the people. No matter where they were from in the Caribbean: the Dutch islands, the British, or the Spanish-speaking countries, it seemed as if the fact that all of us are bathed by the same warm and bright-blue Caribbean sea, magically turns us into a one-big family. After the initial presentations, we were all long-time friends. The shared passion for our birds and our unique ecosystems brings us together despite barriers of language or political systems.

The conference sessions started with an introduction given by Maya Wilson, the Landbird Monitoring Program Manager for BirdsCaribbean. I barely managed to keep seated quietly, because the excitement of being part of such a fascinating project was too much to handle for a ‘hatchling’ like me. While Maya was detailing the goals and scope of the program, my mind was racing, already picturing how much could be done across our islands with such a powerful tool, like PROALAS, to widen our knowledge of our resident and endemic birds. I was not alone in this. The discussions began just as soon as Maya finished her presentation. It was my first glimpse into the amazing community of conservationists gathered in the room.

I learned from the challenges that face birds and their habitats in small and tourism-driven islands like Aruba, Bonaire, or Trinidad and Tobago. I learned first-hand about the hard and successful work done in Antigua to get rid of some invasive species. I marveled at the community-based initiatives that organizations like Para La Naturaleza in Puerto Rico, and Grupo Jaragua and Grupo Acción Ecológica in the Dominican Republic are doing to increase awareness and engage local actors in conservation efforts. And that was just the beginning. Everyone had something to share and while sessions went by, the newly acquired tools made the debates richer and more stimulating for all.

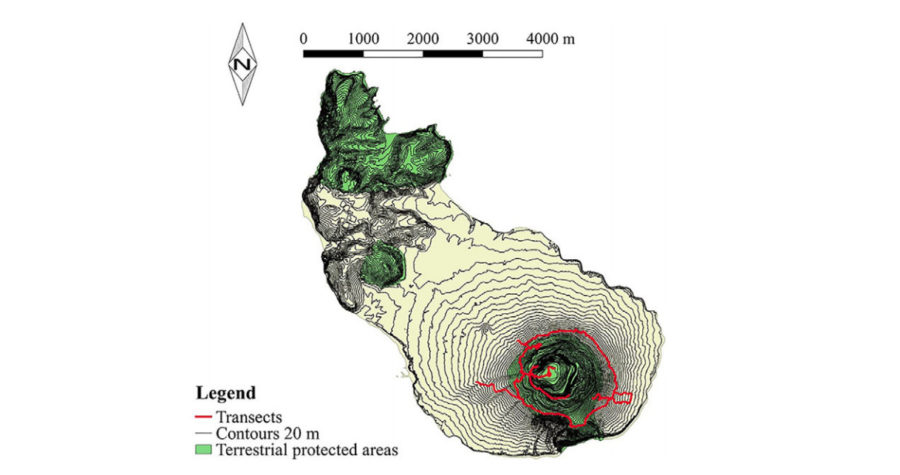

But soon the talks delved into more detailed aspects of landbird monitoring. Entire sessions on the theory behind point counts and transects, survey design and bias minimization, distance estimation, and eBird as a tool for gathering scientific data, comprised most of the morning and afternoon classroom sessions. And of course, how could I forget the introductions into everyone’s favorite subject: statistics. Hopefully, you’ll notice my sarcasm in the last sentence. But I have to give credit to our outstanding teachers: Holly Garrod, Jeff Gerbracht, and especially to Ingrid Molina. Ingrid reminded us all that Costa Rica also shares some Caribbean waves and her special charm and her ease at teaching made it a lot easier for all of us, as we tried to grasp the essentials of occupancy models.

Field Training or Boot Camp?

PROALAS is not a thing you can master just from a classroom. You will need field sessions and some hands-on practice to have a more complete understanding of how it works and how it can be effectively employed for addressing basic research or management objectives. Jarabacoa was the perfect setting for the workshop practice activities. It is home to incredible birds like the endemic Todies (two species!) and the Palmchat, with a variety of habitat encompassing recovered cattle pastures as well as well-preserved evergreen forests.

The morning and afternoon field trips were the most cherished moments of the day for me. They offered the chance to get to know my colleagues more closely and the opportunity to immerse myself in the stunning biodiversity of the Dominican Republic. To meet the first objective, I joined a different field group every time I could. I first hung out with the so-called ‘Latin team’ during the first bird ID training sessions. It was really chaotic for me trying to make sense of the different names we Cubans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans have for the same birds. Bijirita, Ciguita, Reinita – all of them just for warblers. Sometimes we have the same names, but use them for different species, like the name ‘Ruiseñor’, which is the Dominican name for the Northern Mockingbird, while for Cubans it refers to our endemic Cuban Solitaire.

This cultural chaos was just superficial, however. The Latin team felt like home. The large group from the DR consistently exhibited the well-deserved fame of incredibly gracious hosts. I won’t single anyone out because they all, students and trainers alike, left such a profound impact on me that I don’t want to miss out any names. I learned from them all, and their sympathy and good humor made my days in the Dominican Republic one of the most precious memories of my short life. And what to say about the Puerto Ricans! Just that the motto that states that Cuba and Puerto Rico are the two wings of the same bird couldn’t be more accurate and meaningful in this particular setting.

The Latin team was surprised to see that I decided to spend some time with the Dutch Caribbean participants during the next morning’s field trip. I really enjoyed learning how culturally different we are despite being so geographically close. I also, at the cost of some personal embarrassment, realized there were islands which I had never heard of before, like Saba. Even though I felt bad about it, it was an invaluable lesson and represented personal growth. As a result, I updated my 2022 New Year’s resolutions: getting to know more of our Caribbean shared history, nature, and culture.

After a very productive training session establishing PROALAS point counts and transects, and my first time watching the Narrow-billed Tody, we were all back to Rancho Baiguate for more talks. The Latin team was waiting for me to rub my nose in the unique experience that I missed during their trip. They had an amazing opportunity to watch the Antillean Euphonia from a photographer’s perspective. I almost cried.

Before I move on, I must share two more highlights from our field trip experiences, both closely intertwined. First —and the other workshop participants won’t let me lie— never take Holly’s word regarding the trip’s difficulty level as a good standard measure. If Holly assures you that the field paths are going to be child’s play, be sure they WON’T and that you will enjoy, but also suffer every minute of it. And if Holly tells you that it will be a hard and strenuous trail to walk – run for your life, and NEVER, EVER go that way!

The Barbed Wire Deluxe Team can attest to this. Holly is made from another brew not yet understood by us, common folks, and her resistance and fieldwork aptitudes are simply admirable. We deduced that the many years working in the Jarabacoa mountains have made her immune to fatigue. Shanna Challenger, and her other team members, learned that lesson all too well, when, while trying to set some PROALAS point counts they had to jump, climb, and roll (sometimes all at once) to pass a barbed wire fence. Shanna’s witty mind, and contagious sense of humor, came up with the hilarious name of Barbed Wire Deluxe to baptize their team. She made all of us laugh at the joke; it made the event an unforgettable anecdote of the DR workshop.

Ébano Verde and bitter-sweet goodbyes

The days go fast when you’re having fun. During the daily hustle and bustle of setting PROALAS point counts, practicing distance estimation, enjoying the incredible bird diversity of Jarabacoa, and the constant discussions and idea-sharing moments, it was easy to forget what day of the week it was. But Sunday was swiftly approaching and with it, the last day of the workshop. When we thought all the surprises were exhausted, it turned out the organizers were just leaving the best for the end.

The trip to the Scientific Reserve of Ébano Verde, a rainforest paradise rising 800 feet above sea level, was the perfect choice for spending the last moments with our new friends. The stunning diversity of the mountains of the Dominican Republic left us all blown away. There, trees and ferns have a different shade of green. Birds seemed to be aware of that, and their songs were like an ode in celebration of beauty.

Now, I have a confession to make. In Ébano Verde, I felt my national pride quiver. I was lucky to admire the elegant and majestic Hispaniolan Trogon. This vision brought doubts in my mind as to which one was the prettiest: the Cuban Trogon or the Hispaniolan Trogon? This thought haunted me during the entire walk. I almost forgot my internal questioning when I had the chance to watch the other Tody, the Broad-billed, or admire the shiny blend of sky-blue and orange of the Antillean Euphonia, or marveled at the melodious song of the Rufous-Throated Solitaire.

I became easily distracted by birds, and for a moment I was separated from the group. Then, at a twist of the road, my eyes encountered a magical scene. There they were, the Dominicans, triggering with their constant jokes the boisterous laughter from the guys of the Dutch Caribbean. Somewhere close, the Puerto Ricans were showing some birds (and plants) to the girls from Grenada and The Bahamas. A little ahead in the same path were Holly, Ingrid, and Jeff doing some PROALAS point counts with the students from Antigua, Jamaica, and Cayman Islands. And then, the answer came as a realization. It didn’t matter which Trogon was the prettiest. This was not about a contest. All birds are equally important and deserve our utmost commitment to their conservation. That’s why we were there: to learn new skills that will empower us to make more accurate assessments of the health of their populations. To create a strong community of partners across our islands that can work together and spread knowledge and success stories in conservation.

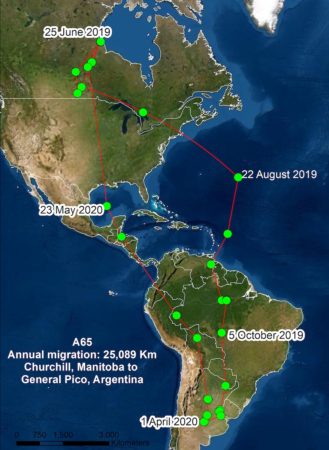

The main lesson I learned during the workshop, I must admit, was not PROALAS-related. The main lesson was that, since birds don’t know or care about borders, countries, or nationalities, we, the “Humans of BirdsCaribbean,” must try to overcome these differences, in order to achieve our supreme goal: jointly working for the conservation of birds and their habitats.

Daniela Ventura is a Cuban ornithologist working in the Bird Ecology Group at the University of Havana. She became interested in birds during her first year in college, where she conducted undergraduate research on the Reddish Egret´s trophic behavior. She is currently a master’s student working on the movement ecology of resident Turkey Vultures. Daniela considers herself a molt nerd, so her future career goal encompasses creating a permanent banding station at the National Botanical Garden in Havana to study molt patterns of Cuba’s resident birds.

Gallery

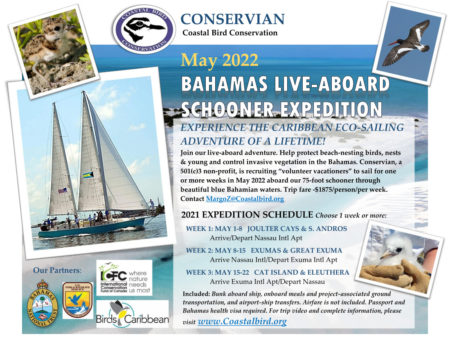

Acknowledgments: BirdsCaribbean is grateful to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for funding to develop our new Landbird Monitoring Program and hold this training workshop. We are also grateful to the US Forest Service International Programs, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and the Dutch Conservation Nature Alliance for additional funding support. Thanks also to Optics for the Tropics and Vortex Optics for providing binoculars for all participants, and to the friendly and helpful staff at Rancho Baiguate for hosting us. A special thank you to interpreter, Efrén Esquivel-Obregón, for his excellent and patient work with the group all week. Finally, we thank BirdsCaribbean members, partners, and donors for your support, which made this work possible.

Related Reading: