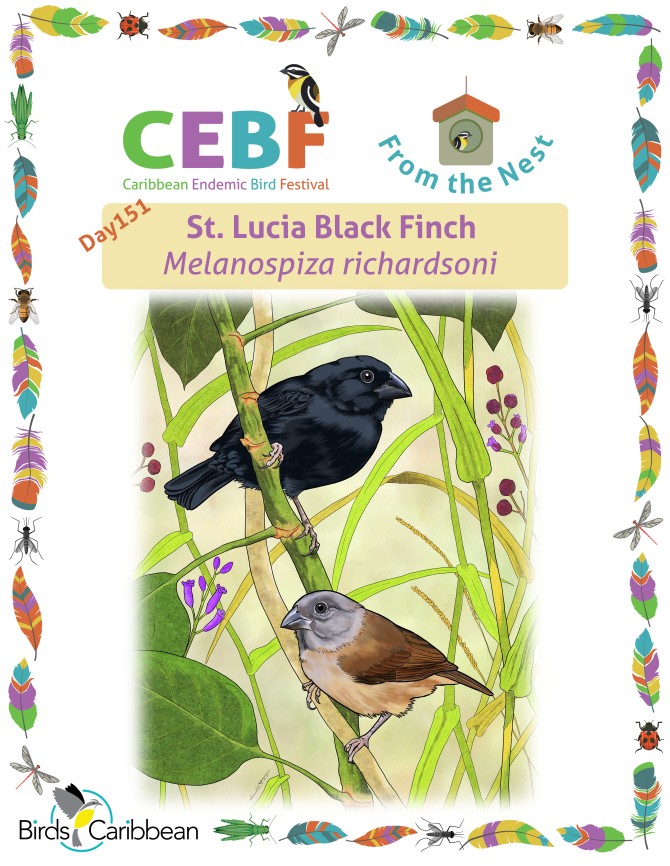

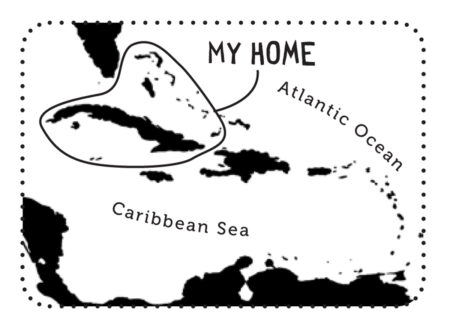

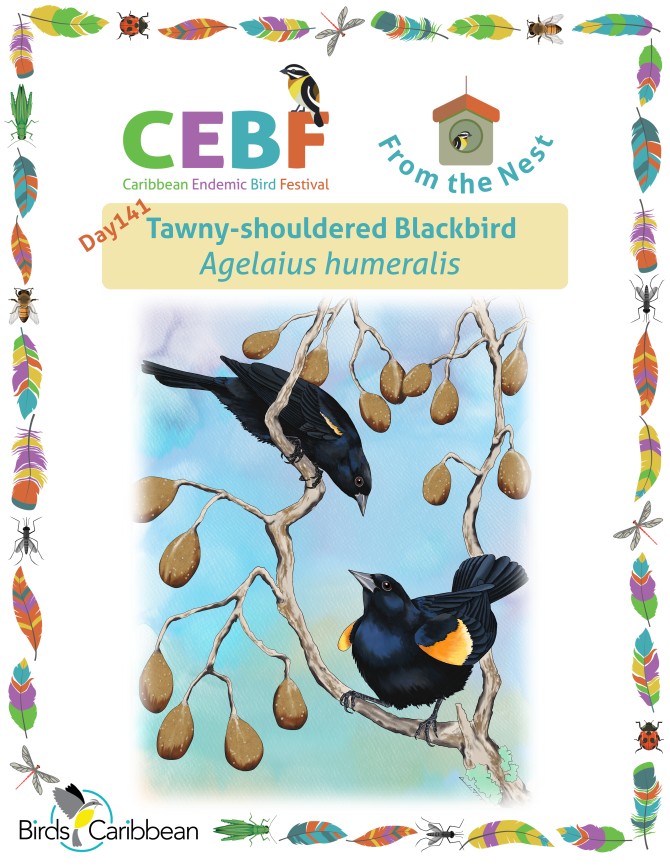

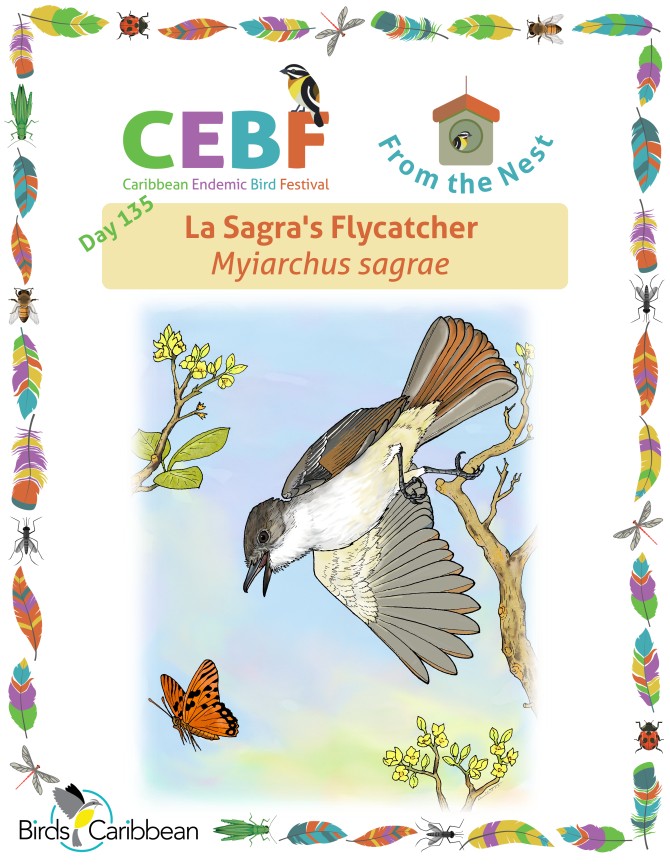

Celebrate the Caribbean Endemic Bird Festival (CEBF) with us! Our theme in 2024 is “Protect Insects, Protect Birds”—highlighting the importance of protecting insects for birds and our environment. Have fun learning about a new endemic bird every day. We have colouring pages, puzzles, activities, and more. Download for free and enjoy learning about and celebrating nature!

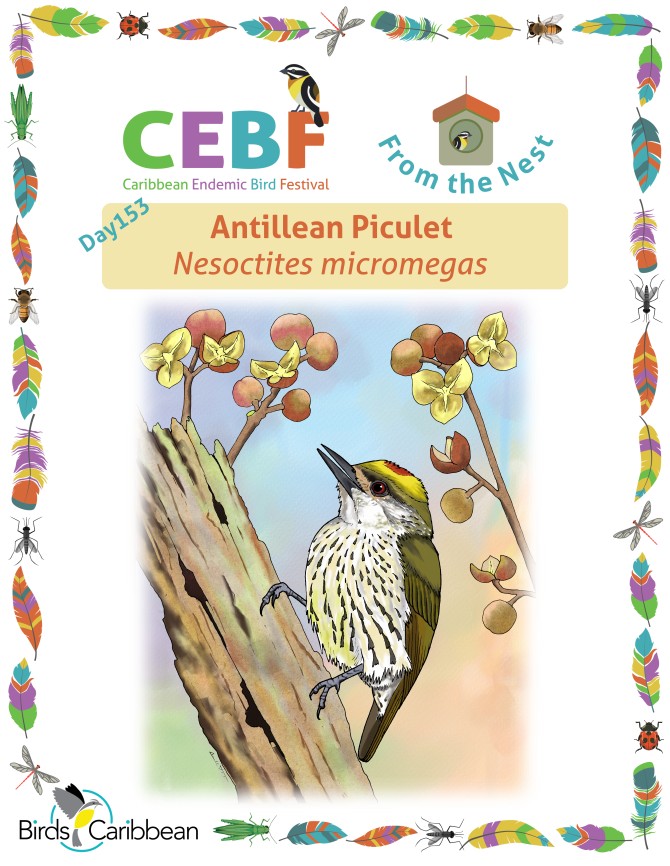

Endemic Bird of the Day: Antillean Piculet

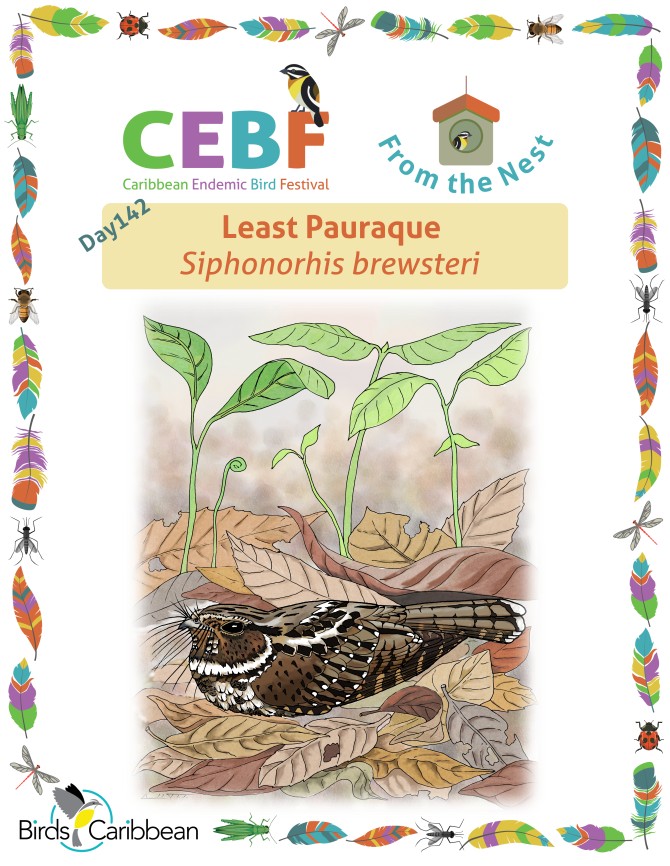

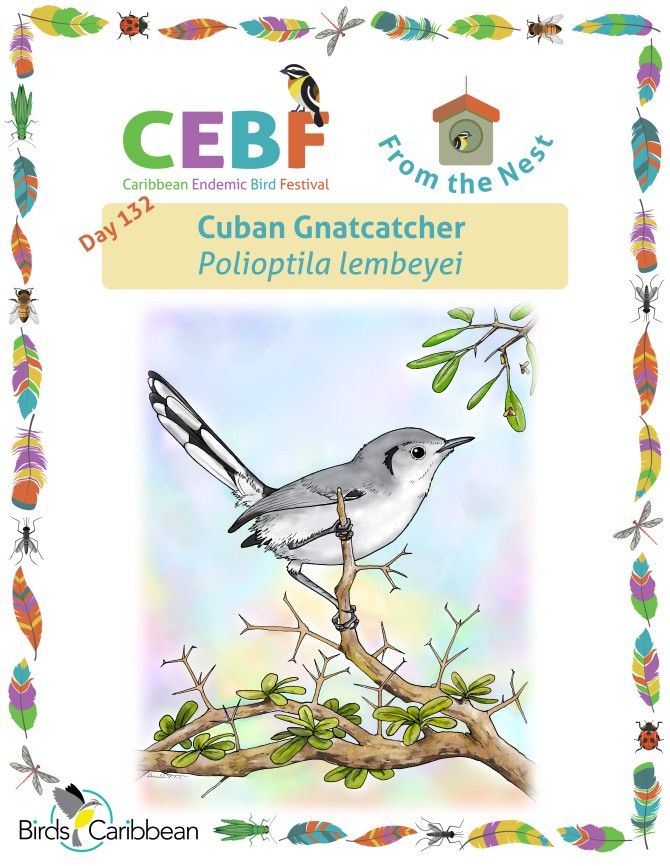

Imagine walking through the dry forests of Sierra de Bahoruco in the southwestern part of the Dominican Republic when, from up above, you hear a whistling, “kuk-ki-ki-ki-ke-ku-kuk”. You stop to look up and you spy a small bird with a large bill and olive-green wings and back! Struck by this curious sight, you quickly begin to search through your field guide and discover that it’s an Antillean Piculet (Nesoctites micromegas), a small relative of the Hispaniolan Woodpecker (Melanerpes striatus).

You focus your binoculars on the diminutive woodpecker and notice the black dots and streaks against the white to whitish-yellow cheek, throat, chest, and belly. As the piculet flutters through the overhead vegetation, you get a great glimpse of the brilliant lemon-yellow crown. After a few minutes of enjoying this wonderful sight, the bird gives a series of “wiiii” calls and is joined by another piculet! This new piculet looks just the same as the one you have been watching—except for a particularly intense orange spot on the top of the bird’s head! This new bird, with its vibrant orange dot, is a male. You’re invested now, and watch as the pair of piculets work their way to the crown of the tree, and take off for the next feeding site—giving a noisy “yeh-yeh-yeh-yeh” as they go.

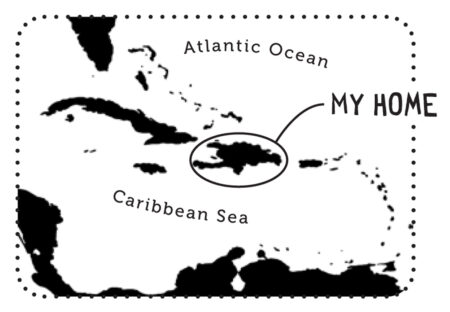

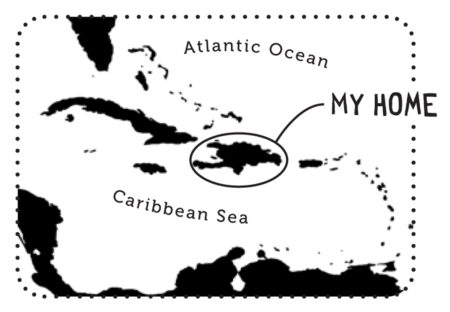

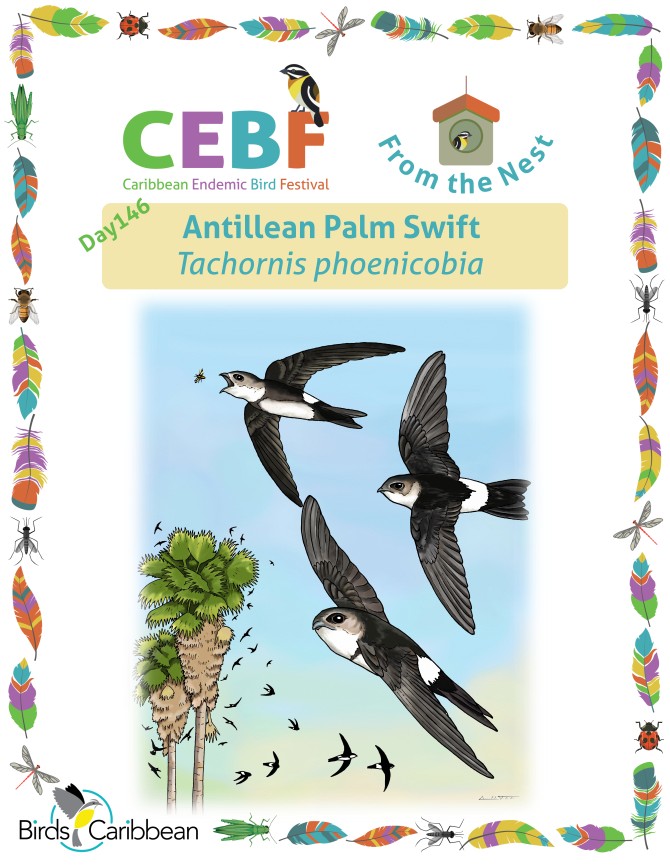

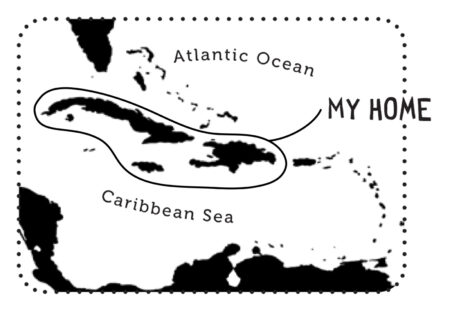

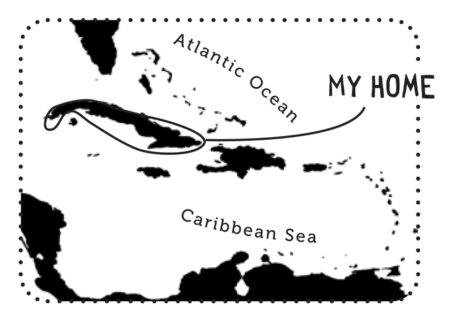

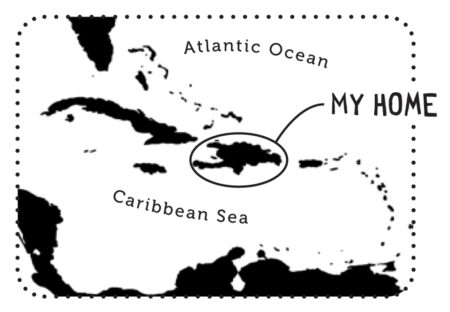

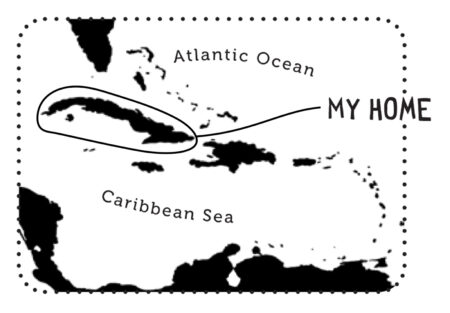

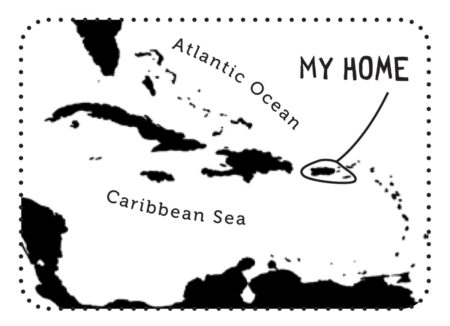

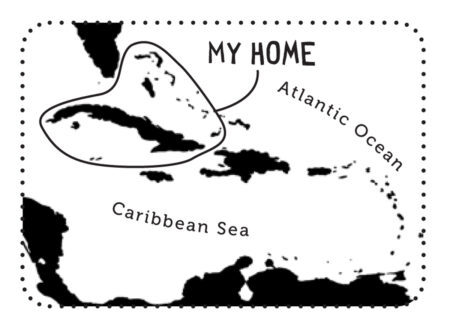

The Antillean Piculet can be found throughout the island of Hispaniola, which includes the Dominican Republic and Haiti, living in many types of habitats including humid to dry primary and secondary forests, pines forests, mangroves, and occasionally fruit orchards. In these habitats, you can find the piculet clinging to vines, tree trunks, and branches, or zipping through vegetation in the understory, searching for tasty insects and fruit.

These small woodpeckers that range in size from 14 to 16 centimeters and can weigh as much as 33 grams (about as heavy as a light bulb!). However, the Antillean Piculet is unlike most woodpeckers because the female is larger than the male! Despite this size difference, both males and females will carve out the cavity and take care of the young during the breeding season which starts in February and ends in July. Cavities may be excavated in trees, palms, and fence posts, or they will use another woodpecker’s abandoned cavity—piculets are not too picky when it comes to finding a nest. In the cavities, the female will lay 2 to 4 glossy white eggs. Scientists do not yet know how long chicks take to hatch or how long they stay in the nests.

The Antillean Piculet has been given the “Least Concern” status by the Global IUCN, but habitat destruction, for development and agriculture, may pose a threat to the species in the future, especially in Haiti. For the survival of this chubby woodpecker, and other insectivores, we remind you to use organic pesticides, and to plant more native than ornamental plants which will attract native insects and provide shelter for birds and other wildlife!

Learn more about this species, including its range, photos, and calls here. Great news! If you’re in the Caribbean, thanks to BirdsCaribbean, you have free access to Birds of the World and you can find out even more in the full species account of this bird!

Thanks to Arnaldo Toledo for the illustration and Qwahn Kent for the text!

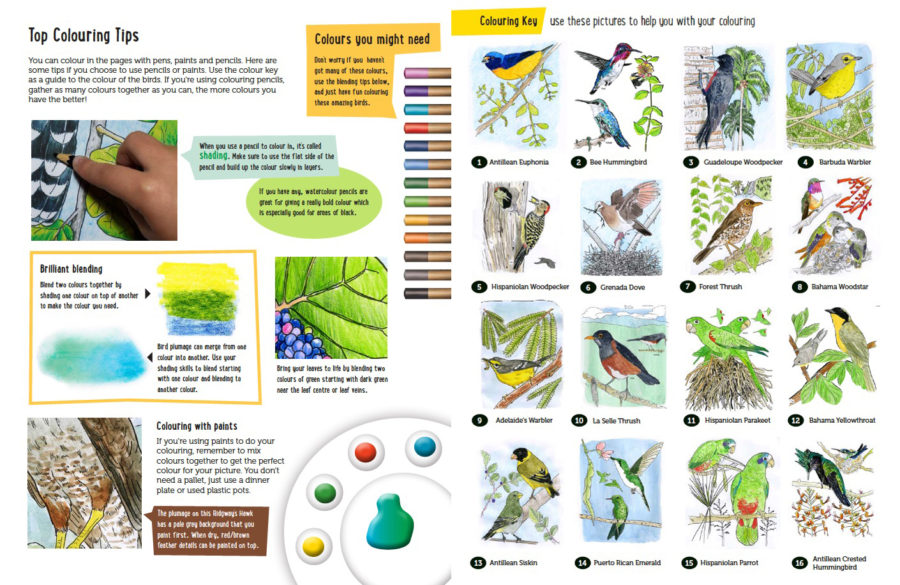

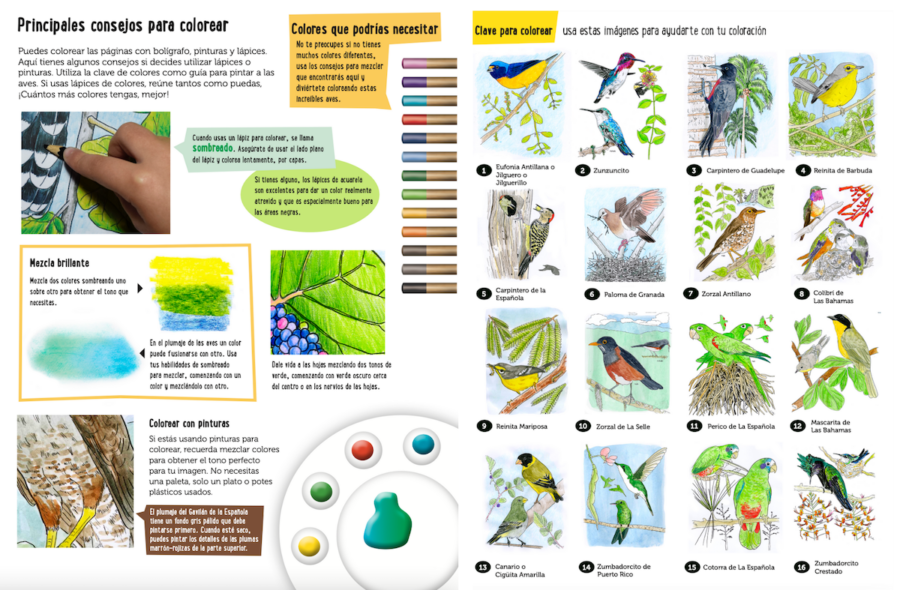

Colour in the Antillean Piculet

Download our West Indies Endemic Bird colouring page. Use the photos below as your guide, or you can look up pictures of the bird online or in a bird field guide if you have one. Share your coloured-in page with us by posting it online and tagging us @BirdsCaribbean #CEBFfromthenest

Listen to the calls of the Antillean Piculet

The call of the Antillean Piculet is a loud staccato “kuk-ki-ki-ki-ke-ku-kuk.”

Puzzle of the Day

Click on the image below to do the puzzle. You can make the puzzle as easy or as hard as you like – for example, 6, 8, or 12 pieces for young children, all the way up to 1,024 pieces for those that are up for a challenge!

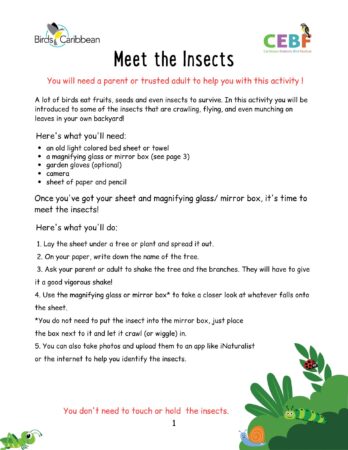

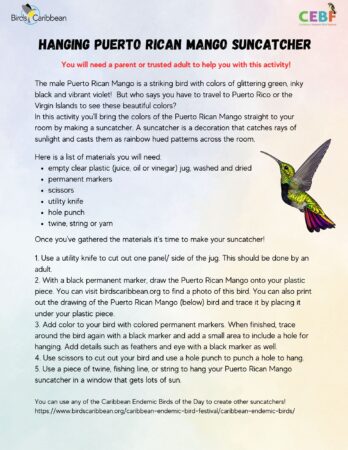

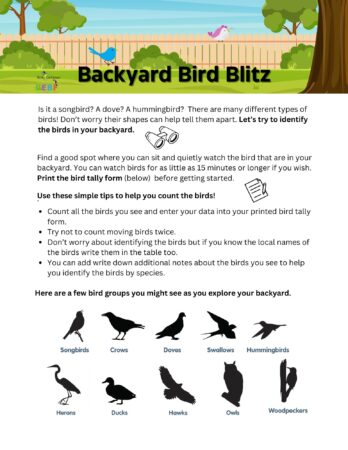

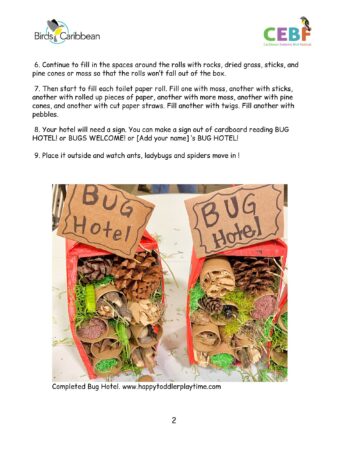

Activity of the Day

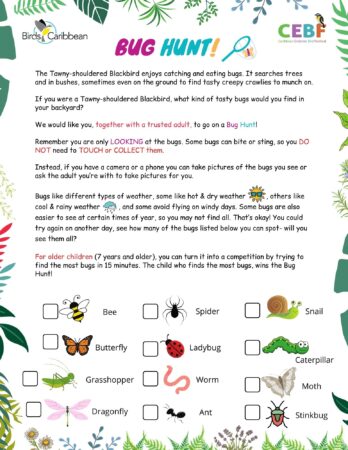

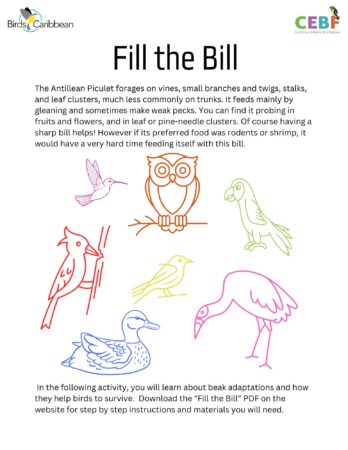

FOR KIDS : Today’s bird the Antillean Piculet searches vines, small branches and twigs, stalks, and leaf clusters for insects to eat! It feeds mainly by gleaning (‘picking’ insects of the surface of leaves, branches etc.) but will sometimes also make weak pecks in search of food items. You can find food by probing in fruits and flowers, and in leaf or pine-needle clusters. Of course having a sharp bill helps!

FOR KIDS : Today’s bird the Antillean Piculet searches vines, small branches and twigs, stalks, and leaf clusters for insects to eat! It feeds mainly by gleaning (‘picking’ insects of the surface of leaves, branches etc.) but will sometimes also make weak pecks in search of food items. You can find food by probing in fruits and flowers, and in leaf or pine-needle clusters. Of course having a sharp bill helps!

But birds that eat rodents, flower nectar or shrimps all need very different shaped bills feed themselves! In the following activity, you will learn about beak adaptations and how they help birds to survive.

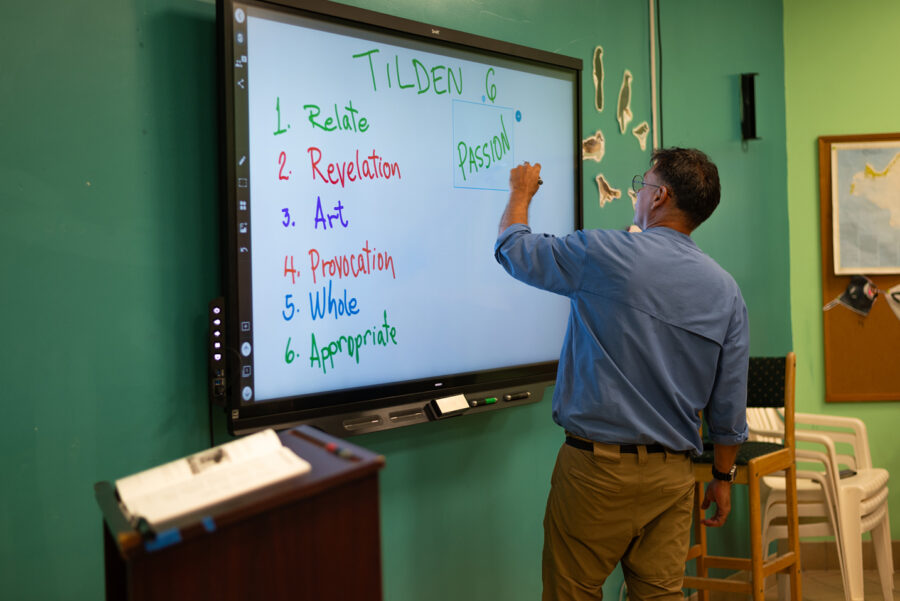

You can find out more in our activity introduction here. You can find all the information, instructions, a guide to learning objective in our “Fit the Bill” activity guide and materials. This activity is perfect to play with school groups or outdoor education clubs etc.

FOR KIDS AND ADULTS : Enjoy this video of an Antillean Piculet in the wild!