The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology publishes the peer-reviewed science on Caribbean birds and their environment that is so important to inform conservation work. In this annual blog feature, JCO’s staff is proud to show off the amazing research from scientific teams around the Caribbean. Let your curiosity lure you into exploring:

Warblers eat lizards and fish? What is the preferred snail diet of the Grenada Hook-billed Kite? How can nesting success of terns be improved? There was once a Giant Barn Owl roaming Guadeloupe?

Look back and discover how James Bond, a pioneer of Caribbean ornithology, relied on the expertise of little-known Caribbean experts. Or look forward and reflect on the future prospects for bird conservation in our age of unprecedented human impact on Caribbean nature.

As JCO’s Managing Editor, I am immensely grateful for a dedicated team of editors, reviewers, copyeditors, proofreaders, and production specialists that have worked together so well this past year to produce high-quality publications. And of course, our fabulous authors that do the work on the ground to help us better understand the biodiverse Caribbean and the challenges it faces. With the non-profit BirdsCaribbean as our publisher, JCO emphasizes access: trilingual content, support for early-career researchers, and open access–from the latest article to the very first volume from 1988.

While our 100% open-access publication policy is the most prominent and public-facing feature of our work at the journal, there has been a lot going on “behind the scenes” as well.

In 2022, JCO welcomed Caroline Pott, our new Birds of the World (BOW) Coordinator, and huge thanks to our outgoing first BOW coordinator, Maya Wilson! Caroline works with authors and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to produce BOW accounts of Caribbean bird species. Zoya Buckmire took the reins as the new JCO Lead Copy Editor, and helped to recruit Laura Baboolal and Kathryn Peiman to the copyediting team. Dr. Fred Schaffner will join us for editorial help with English manuscripts from authors for which English is not their first language. Joining our Associate Editor board were Dr. Virginia Sanz D’Angelo, Caracas, Venezuela, Dr. Jaime Collazo, North Carolina, and Dr. Chris Rimmer, Norwich, Vermont. We are looking forward to hearing from you, our readers and supporters, and working with the JCO team in 2023!

With Volume 35, JCO introduced the assignment of a unique Digital Object Identifier (DOI) to each article, making it easier fo the scientific community to locate an author’s work in the published literature.

— Joseph M. Wunderle, Jr., JCO Editor-in-Chief | jmwunderle@gmail.com

— Stefan Gleissberg, JCO Managing Editor | stefan.gleissberg@birdscaribbean.org

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology relies on donations to keep all of our publications free and open-access. Support our non-profit mission and give a voice to Caribbean ornithologists and their work by becoming a supporter of JCO. Consider being a sustainer with monthly contributions of $5 or more!

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology relies on donations to keep all of our publications free and open-access. Support our non-profit mission and give a voice to Caribbean ornithologists and their work by becoming a supporter of JCO. Consider being a sustainer with monthly contributions of $5 or more!

RESEARCH ARTICLES AND NOTES

-

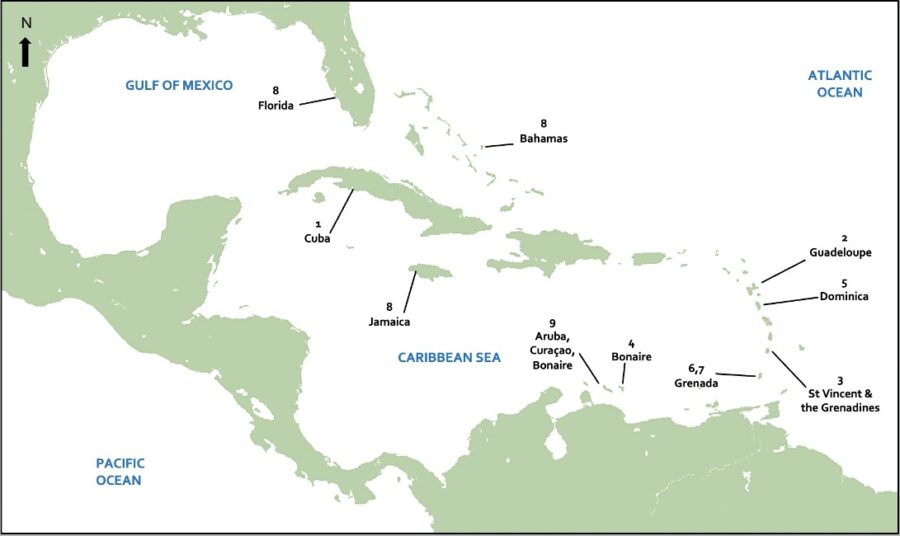

Inventory of birds in different plant formations in the protected area Cueva Martín Infierno, south-central Cuba

Rosalina Montes Espín and Minerva Sánchez-Llull

The Cueva Martín Infierno protected area in Cuba is well-known for its cave and stalagmite formations, but what about its bird community? Located in the Guamuhaya Mountains, one of Cuba’s biodiversity hotspots, this protected area is sure to support a thriving bird community, but this aspect is previously undocumented. In this paper, Montes and Sánchez-Llull present the first comprehensive record of birds in Cueva Martín Infierno, including several endemics and species of conservation concern.

-

Evidence of a Late Holocene giant barn owl (Aves: Strigiformes: Tytonidae) in Guadeloupe

Monica Gala, Véronique Laroulandie, and Arnaud Lenoble

What has two talons, feeds on large rodents, and used to roam the Caribbean night sky? Giant owls! Giant barn owls (Tytonidae) once inhabited the Caribbean in precolonial times, as evidenced by recent palaeontological research. In this paper, Gala et al. describe a bone fragment of an unspecified giant barn owl found on Guadeloupe, the second such record for the Lesser Antilles.

-

Marine litter incorporation into nest construction and entanglement of Brown Noddies (Anous stolidus) in the Grenadines, West Indies

Juliana Coffey

Plastic waste is an increasing source of pollution worldwide, especially in marine environments. Seabirds are particularly vulnerable to marine litter, as they can ingest, become entangled in, or incorporate this waste into their colonies and nests. In this research note, Coffey reports on two Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus) interactions with marine litter in the Grenadines, one instance of nest incorporation and another of entanglement and mortality.

-

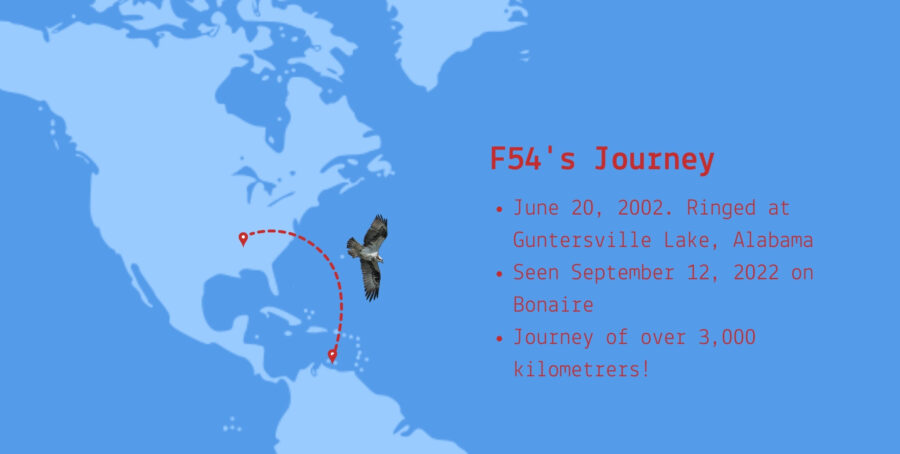

Conservation opportunities for tern species at two Ramsar sites on Bonaire, Caribbean Netherlands

Fernando Simal, Adriana Vallarino, and Elisabeth Albers

The hypersaline lagoons of northern Bonaire are home to several populations of seabirds, making it a regionally significant nesting site in the southern Caribbean. Among the species that breed there are the Eastern Least Tern (Sternula antillarum antillarum), Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), Royal Tern (Thalasseus maximus), and Cayenne Tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis eurygnathus). In this paper, Simal et al. quantify breeding success for the terns at these sites in Bonaire, and provide timely recommendations for increasing tern populations, such as island creation and predator exclusion.

-

The short-term impacts of Hurricane Maria on the forest birds of Dominica

Andrew Fairbairn, Ian Thornhill, Thomas Edward Martin, Robin Hayward, Rebecca Ive, Josh Hammond, Sacha Newman, Priya Pollard, and Charlotte Anne Palmer

How are hurricanes affecting Caribbean landbirds? Like other native species in the region, birds likely evolved under the threat of hurricanes, but as climate change increases the frequency and intensity of storms, this question becomes increasingly important. In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017, Fairbairn et al. sought to compare the bird community on Dominica to that pre-hurricane. In this paper, they present those results, including the disproportionate effects on some functional groups that may predict which species fare better long-term.

-

Variability of the Grenada Hook-billed Kite (Chondrohierax uncinatus mirus) diet

Arnaud Lenoble, Laurent Charles, and Nathalie Serrand

It’s a well-known fact that Hook-billed Kites eat snails- their wonderfully adapted bills tell us that much. But, will any old snail do, or do these high-flying molluscivores have a preference? In this paper, Lenoble et al. present their observations on the diet of the Grenada Hook-billed Kite (Chondrohierax uncinatus mirus), with prey availability and distribution having the potential to inform conservation planning for this endemic subspecies.

-

Status and distribution of the Antillean Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus antillarum) on the island of Grenada

Ezra Angella Campbell, Jody Daniel, Andrea Easter-Pilcher, and Nicola Koper

How is the Antillean Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus antillarum) faring habitat loss and degradation across its small-island ranges? Campbell et al. aim to investigate the status and distribution of this species in Grenada, comparing its distribution by habitat, elevation, and season. In this paper, they present their results as well as recommendations for the conservation of this species that are applicable both to Grenada and across its Caribbean range.

REVIEWS

-

A review of wood warbler (Parulidae) predation of vertebrates and descriptions of three new observations

Michael E. Akresh, Steven Lamonde, Lillian Stokes, Cody M. Kent, Frank Kahoun, and Janet M. Clarke Storr

Wood warbler (Parulidae) diets are varied and interesting, from arthropods to fruits and sometimes even nectar. Occasionally, wood warblers may also consume vertebrate species, primarily Anolis lizards, but these instances are not well documented and have not previously been compiled. In this paper, Akresh et al. present a comprehensive literature review on wood warbler vertebrate consumption throughout the Caribbean and USA, and also describe three new observations from The Bahamas, Jamaica, and Florida.

-

Status of the Red-billed Tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) on and around the islands of Aruba, Curaçao, and Bonaire

Jeffrey V. Wells, Elly Albers, Michiel Oversteegen, Sven Oversteegen, Henriette de Vries, and Rob Wellens

The Red-billed Tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) is a stunningly charismatic seabird without many documented or published records in the southern Caribbean until recently. To shed light on this species’ distribution and trends over the decades, Wells et al. sought to compile records from near the islands of Aruba, Curaçao, and Bonaire. This review accompanies an erratum note in this issue, and details all previous sightings of the species, with records as far back as 1939.

PERSPECTIVES AND OPINIONS

-

James Bond (1900–1989)—US ornithologist—and his network of contributors to the avifauna of the West Indies

Gerhard Aubrecht

James Bond, renowned ornithologist of the 20th century and the namesake of 007, contributed dozens of publications to the field of Caribbean ornithology. Throughout his decades of work, he established a network of scientists and laypeople alike, without whom his work would not have been possible. In this Perspectives and Opinions piece, Aubrecht compiles the biographies of Bond’s most important contributors, highlighting the importance of collaboration and networking in advancing scientific study across the region.

-

The future of Caribbean endemic bird conservation in the Anthropocene

Howard P. Nelson and Eleanor S. Devenish-Nelson

The Caribbean Biodiversity Hotspot is well-known for its avian diversity, with over 700 species! Of which more than 180 are endemic. Unfortunately, the wellbeing of these avian populations is often constrained by the inherent challenges of small island developing states, increasing effects of climate change, and colonial histories. In this piece, Nelson and Devenish-Nelson explore these challenges, with concrete examples of endemic birds across the region, and describe a possible way forward for regional conservation of our species as we navigate the Anthropocene.

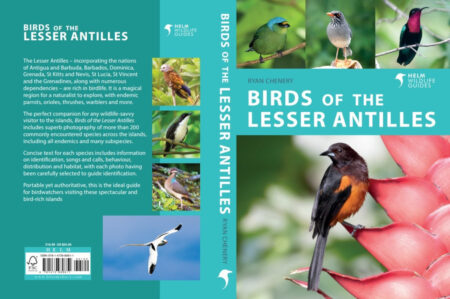

BOOK REVIEWS

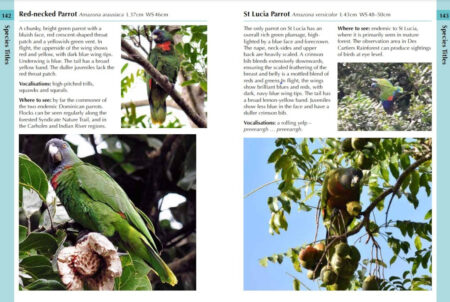

Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

Book Authors: Herbert A. Raffaele, Clive Petrovic, Sergio A Colón López, Lisa Yntema, and José A. Salguero Faria

Book review by: Joseph M. Wunderle, Jr

The Puerto Rico Breeding Bird Atlas

Book Authors: Jessica Castro-Prieto, Joseph M. Wunderle, Jr., José A. Salguero-Faria, Sandra Soto-Bayo, Johann D. Crespo-Zapata, and William A. Gould

Book review by: Leopoldo Miranda-Castro

RECENT ORNITHOLOGICAL LITERATURE (ROL) FROM THE CARIBBEAN

Recent ornithological literature from the Caribbean – 2022

Steven Latta

The annual compilation of the most important articles that appeared elsewhere, annotated by Steve Latta.

Article by

Zoya Buckmire – Lead Copy Editor for the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

Stefan Gleissberg – Managing and Production Editor for the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology relies on donations to keep all of our publications free and open-access. Support our non-profit mission and give a voice to Caribbean ornithologists and their work by becoming a supporter of JCO.

![PIPLFW[YA]andFL[8P]CINSnorthbeach-Patrick-Leary Banded Piping Plovers](https://i0.wp.com/www.birdscaribbean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/PIPLFWYAandFL8PCINSnorthbeach-Patrick-Leary.jpg?w=400&h=287&ssl=1)