I wanted to get to know the elusive Whistling Warbler on the island of Saint Vincent — which meant that we needed to go up. Straight up some very steep slopes!

The Whistling Warbler (Cathoropeza bishopi) is an endangered, endemic species of bird that lives on the Lesser Antillean island of Saint Vincent. When we say a species is endemic, it means that the species exists nowhere else on the planet other than at a discrete location. This is a common designation for many island species. When a species is endemic and endangered, that can be a ‘code red’ for conservationists — because the species has nowhere else to go to disperse from threats! In the case of the Whistling Warbler, those threats come mainly from deforestation, land use change, hurricanes (exacerbated by climate-change), and the recent explosive eruption of Saint Vincent’s La Soufrière volcano in 2021, the largest to occur in the Caribbean in the last 250 years.

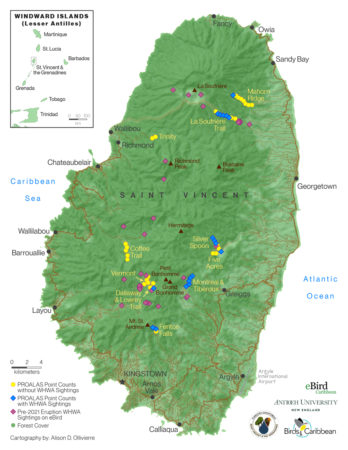

So where is the Whistling Warbler to be found? Well, this charming bird (whose plumage delightfully brings to mind an Oreo cookie!) appears to require a specific kind of natural forest for habitat: forests growing in steep, wet, montane environments. These mostly grow on the windward (east) side of the island. However, these forests have been experiencing a great deal of “wear and tear” in recent years. Some have been cut to grow non-native tree plantations, or terraced to provide farmland, in some cases for the illegal cultivation of Cannabis. Many of the northern areas were decimated by wind and volcanic ash from the 2021 volcanic eruption. The windward forests also take the brunt of hurricanes moving west across the Atlantic, which can wreak havoc on the essential habitat of the warbler. Hurricane Beryl just recently tore through St. Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG); the extent of the damage to the mainland forests (and the warbler) is currently unknown, though nearby Union Island has been devastated. These growing and more frequent impacts of climate change cannot be overlooked.

And yet, the Whistling Warbler has so far been able to hold on in small numbers, in the face of these daunting challenges to its habitat. Much of its success is thanks to conservation efforts that protect and restore their habitat. Now, it is absolutely vital that the warbler population is actively monitored to ensure its survival, and to inform future conservation efforts aimed at protecting its habitat. Part of the challenge here is that there is still so little known about this bird. We don’t know much about their habitat requirements; their nest construction; and when and where they breed. It is critical to understand these aspects of the warbler’s life cycle to make effective management decisions. We can only find this information by getting people out into the forest to make these discoveries and to monitor the population.

Preparing for the trip: some homework required

I am a graduate student at Antioch University New England studying Conservation Biology. Antioch Professor Dr. Mike Akresh has been working with Caribbean birds for over a decade, and when he asked if I would like to accompany him on a two-week field study trip in March 2024 to Saint Vincent, I was initially apprehensive. Leaving my young child and a pile of school work at home for two weeks sounded daunting, but I knew there was important work to be done on Saint Vincent as there is not an overabundance of researchers working on the Whistling Warbler. I made the decision to go.

Firstly, I went into an intense learning period focussed on the birds of Saint Vincent; it was especially important to learn their calls. With the help of eBird, the Merlin App, and a handy field guide to the “Birds of the West Indies,” I familiarized myself with most of the birds we could expect to encounter on the trip. How were we going to monitor for the Whistling Warbler? Well, we were planning to work with the PROALAS landbird monitoring protocol, which requires us to document every bird seen and heard during a specific period of time at a point or transect. Every bird has a story to tell about the environment; birds are regarded as indicator species. This means that the presence of certain species or lack thereof provides critical insights about the impacts of land use change, climate change, and volcanic activity; in other words, the obstacles and challenges that the Whistling Warbler faces.

The song of the Whistling Warbler consists of an ascending trill of loudly whistled notes.

Our enthusiastic team on Saint Vincent

Our collaborators on the island were the talented and professional members of the SVG Forestry Department. Our point of contact and monitoring collaborator was the energetic Glenroy Gaymes, who has been working closely with the Whistling Warbler conservation efforts. Glenroy is an expert birder and naturalist, whose passion for conservation on Saint Vincent is infectious. With invaluable help from Glenroy and other Forestry staff such as Felicia Baptiste, Romano Pierre, Caswin Caine, and Kishbert Richards, we reached the steep and remote areas where the warbler lives. Glenroy and the Forestry Department have also been monitoring the endemic and endangered Saint Vincent Parrot (Amazona guildingii) and many other non-bird species.

Our days on Saint Vincent were demanding, but rewarding. We did find the Whistling Warbler!

Every morning we would wake up before sunrise, and head up into the sawtooth-like mountains, shrouded in mist. You may have seen these impressive mountains before if you have seen the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, which were largely filmed on Saint Vincent. Fortunately, we encountered the Whistling Warbler several times at various locations. In keeping with previous observations, most or all of our encounters with the Whistling Warbler took place over 300 meters and in steep, wet forests. Did I mention that we had to go up high? The slopes of the misty mountains of Saint Vincent were steep and slippery.

Notes from the field

When studying where Whistling Warblers like to live, we found that they prefer primary forests with lots of moss. Younger and older secondary forests had fewer warblers. Interestingly, palm brakes were about the same as primary forests for warbler sightings, especially near certain trails. Detection was low in elfin woods, which seem to be unsuitable habitat for them. The drier, western side of the island has less of the wet montane forest they prefer.

We noticed that Whistling Warblers really like wetter forests, especially where there’s a lot of moss. For example, at one site – Silver Spoon, where the forest is very wet, we found lots of warblers. However, on the leeward side of the island, the forests were dry and grassy, and we didn’t find any warblers there.

We didn’t look for warblers in the northern part of the island because it’s too dry and no warblers have ever been found there. Tree plantations were the least likely place to find Whistling Warblers because these areas have trees, like Blue Mahoe and Big-leaf Mahogany, that are all the same age and don’t provide enough food or shelter for the birds. Overall, we also noticed that there were fewer other forest birds around areas affected by the volcano. Birds like Bananaquits and House Wrens were common near the volcano, but other species like Cocoa Thrush and Ruddy Quail-Doves were missing. The ash from the volcano may have made it harder for some birds to find food. However, some of these birds are starting to come back now, so we’ll keep studying and monitoring the area to learn more.

We still need more information on the mysterious Whistling Warbler!

Over the past few years and during this current trip, we have come across several nests that might possibly be those of the Whistling Warbler, but without a positive ID of a warbler using the nest, we cannot say for sure. Finding a nest is particularly important for conservation efforts because it allows us to better understand the warbler’s breeding ecology and habitat requirements. We also do not know how successful the warbler is in breeding; invasive mongoose or black rat populations may prey on eggs or fledglings. But it must be acknowledged that without more research, we cannot know for sure. There are limited resources available to protect the Whistling Warbler, so the more specifics we have about this species, the better those resources can be utilized to have the greatest conservation impact. We need to know more, so that we can do a better job at protecting this species, which is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

With the data we have been able to collect while on Saint Vincent, we aim to create a conservation action plan (CAP) specifically for the Whistling Warbler. Without the dedicated work of the Saint Vincent Forestry Department, BirdsCaribbean, and donors small and large, this work would not be possible, and the Whistling Warbler would likely be added to the alarming (and growing) number of species lost forever.

We owe it to the Whistling Warbler, up there in the remote rainforest and beautiful mountains of Saint Vincent.

Christian Carson is a graduate student at Antioch University New England studying conservation biology. He is interested in ways people seek and find meaning in the living world, and how this meaning (or lack thereof) shapes global environmental issues. He lives with his partner and three-year-old son in Western Massachusetts. He enjoys quiet walks in the woods, flying kites, and sitting zazen. You can reach him at ccarson@antioch.edu.

Acknowledgements: BirdsCaribbean is grateful to the Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund (CEPF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for funding our Conservation of the Endangered Whistling Warbler Project, launched in 2022. We are also deeply grateful to Mr. Fitzgerald Providence and his staff at the St. Vincent Forestry Department for their help and support. Special thanks Glenroy Gaymes, who has been working closely with us on the warbler project. Finally, we thank BirdsCaribbean members, partners, and donors for your support, which made this work possible.