Laura McDuffie, a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Management Program, has been tracking the movements of Lesser Yellowlegs on their migration. Find out more about Laura’s work, the amazing journeys that Lesser Yellowlegs make each year and the threats they face along the way! Scroll down to see Laura’s webinar on the Lesser Yellowlegs with much more information on her research. Also check out our NEW short video on Lesser Yellowlegs and hunting in the Caribbean (below and on our YouTube).

Typically, when people think of shorebirds, they envision gangly, long-billed birds probing for invertebrates along sandy or rocky coastlines. But this is not where you are likely to find our study species, the Lesser Yellowlegs! This medium-sized shorebird breeds in the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada. They can be found in a diversity of wetland habitats during migration and overwintering in the Caribbean and Central and South America. This includes salt, brackish, and freshwater ponds and swamps, mud flats, mangroves, and other water edges. They are particularly fond of freshwater swamps and may also be found in large numbers on flooded agricultural fields (especially rice fields) if available, as in Suriname, Cuba, and Trinidad.

Shorebirds in Trouble

Over the past five decades, shorebirds have declined at an unprecedented rate. Factors causing this decline include habitat destruction and alteration, agrochemical applications, climate change, and for some shorebirds, including the Lesser Yellowlegs, unsustainable harvest at several non-breeding locations. Harvest occurs as sports hunting in the Caribbean, as well as hunting and trapping for sale as food, as a source of income in other parts of the flyway. Lesser Yellowlegs populations have declined by an alarming 63 ̶70% since the 1970s!

Keeping Track of Lesser Yellowlegs

In May 2016, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Management Program began deploying tracking devices (light-level geolocators) on breeding Lesser Yellowlegs in Anchorage, Alaska. Our goal was to determine where the species occurs during the non-breeding season. In 2017, birds returned to the breeding sites. To our dismay, however, they were incredibly difficult to recapture so that we could retrieve the tags and the data. This serious predicament ultimately made us have a “rethink” about our objectives for the Program. As a result, we expanded the range of our study to include collaborations with Kanuti National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska; Yellowknife, Northwest Territories; Ft. McMurray, Alberta; Churchill, Manitoba; James Bay, Ontario, and Mingan Archipelago, Quebec.

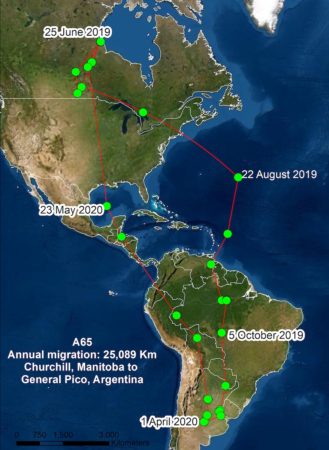

During the summers of 2018-2021, partners at Alaska Department of Fish and Game (Katherine Christie), USFWS (Christopher Harwood), Environment and Climate Change Canada (Jennie Rausch, Christian Friis, and Yves Aubrey), and Trent University (Erica Nol) deployed Lotek wireless GPS pinpoint tags on breeding adults. These tags record data via satellite so recaptures are not required! The GPS tags are accurate to ~10m, which has allowed us to examine the occurrence of Lesser Yellowlegs in countries where shorebirds are harvested. Since 2018, we have successfully deployed 115 GPS tags on Lesser Yellowlegs!

Amazing Journeys Revealed

Each bird we tag and release has their movements tracked, which mean we can identify the different countries they visit and specific sites they use during migration and overwintering. This information can help us to identify the potential bottlenecks and threats that birds experience each year.

Here is just one amazing journey made by “JP” who was tagged in Anchorage, Alaska in 2018. The tag revealed that he travelled at least 10,576 km on his southward migration, taking in Alberta and Manitoba, Canada, and Devils Lake, North Dakota, on his way through North America. JP then spent a whole month on Barbuda! This highlights how important the Caribbean can be as a rest and refueling spot for some shorebirds. Finally, JP made it to Middenstandspolder, in Suriname, where his tag went offline in February 2019.

We don’t know why JP’s tag stopped transmitting. It was not uncommon in our study to have incomplete tracklines. For these birds, the battery of the tag may have failed, or the harness could have fallen off and left the tag lying covered in mud, unable to recharge and transmit. However, we do know that some birds don’t survive the long journey.

Thanks to strong collaborations with biologists working in the Caribbean, we were able to receive some shorebird harvest reports. In fall 2020, we learned that two of our tagged birds “O2A” and “A65” were shot by hunters in Guadeloupe and Martinique, respectively. This shows that hunting isn’t only a “predicted threat” to the birds we studied, but also a real and observed threat.

find out more about Lesser Yellowlegs and hunting in the Caribbean in this short video

Globally, Lesser Yellowlegs are in steep decline, with likely only 400,000 individuals remaining. Our research on the species has helped identify several potential threats, but we still need to learn more about the hazards these birds face. So, we must rely on assistance from local biologists, managers, hunters, and the public in the Caribbean and beyond.

The proper management of a species ensures that it will be around for future generations to enjoy and utilize. Awareness and education about the species decline and an understanding of the threats it faces can go a long way! When the general public is aware of an issue, they are more likely to take actions. These might include helping to monitor birds, conserving local wetlands, or ensuring that hunting laws protect vulnerable species. They may even participate in scientific efforts, such as submitting shorebird harvest records to managers. Awareness, information gathering and partnerships are critical components in helping us to protect these unique shorebirds.

Laura McDuffie has been studying the breeding and migration ecology of Alaska’s shorebirds and landbirds since 2014. In spring 2021, Laura completed her master’s degree in biological sciences at the University of Alaska Anchorage. Laura’s thesis is entitled “Migration ecology and harvest exposure risk of Lesser Yellowlegs.”

This study would not have been possible without the tremendous efforts of our collaborators. Our gratitude goes out to the following people: Brad Andres, Yves Aubry, Erin Bayne, Christophe Buidin, Katherine Christie, Ken Foster, Christian Friis, Autumn-Lynn Harrison, Christopher Harwood, James Johnson, Kevin Kardynal, Benoit Laliberte, Peter Marra, Erica Nol, Jennie Rausch, Yann Rochepault, Sarah Sonsthagen, Audrey Taylor, Lee Tibbitts, Ross Wood, Jay Wright, and all the field technicians that helped with banding. Kristy Rouse, Cassandra Schoofs, and Brent Koenen with Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson’s 673rd CES/CEIS supported the project from the beginning and were instrumental in the DoD’s recognition of lesser yellowlegs as a Species of Special Concern. Funding sources include the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Bird Studies Canada; Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Smithsonian Institution; the 673rd CES/CEIS, U.S. Department of the Air Force; and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.