The bird world holds quite a few unsolved mysteries—in the Caribbean, too. One of these is the intriguing story of the Jamaican Petrel, which unfolded at a webinar on September 17th. Dr. Leo Douglas, Past President of both BirdsCaribbean and BirdLife Jamaica, and now Clinical Assistant Professor at New York University (NYU), led the conversation with Adam Brown, Senior Biologist at Environmental Protection in the Caribbean (EPIC). Participants were treated to some fascinating stories from the field about petrels, that led towards a glimmer of hope for the bird.

The question is this: Is the Jamaican Petrel, long considered extinct, still alive? As Dr. Douglas pointed out, so many Caribbean endemic birds are “languishing in the drawers of museums around the world,” including at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Dr. Douglas admits that, like Adam Brown, he has “a bit of an obsession” with petrels.

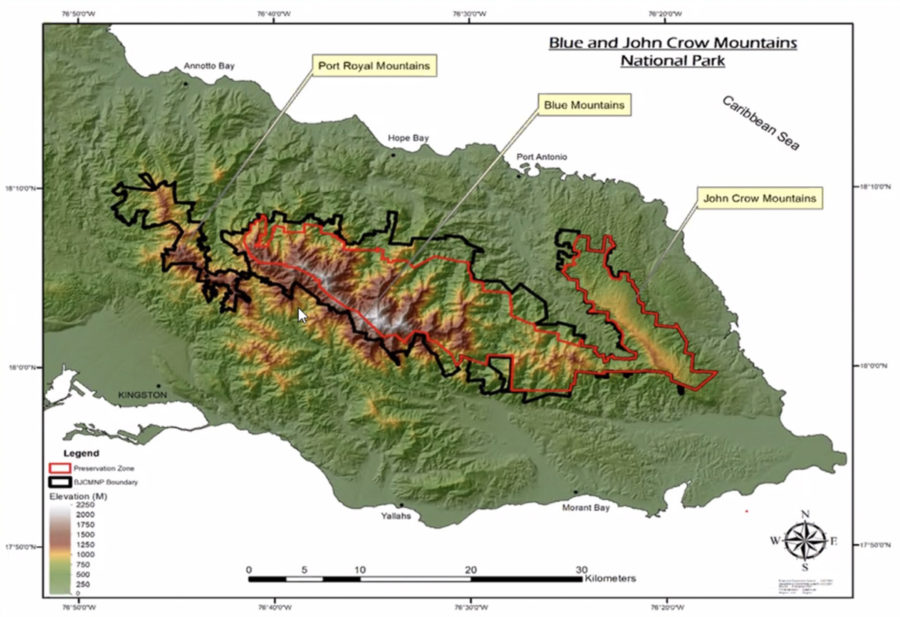

The Jamaican Petrel (Pterodroma caribbaea) was said to have nested in the Blue Mountains, where specimens were collected up to 1879.

Finding the bird on land has proved to be a tremendous challenge, since like other petrels it nests in burrows at five to six thousand feet up. The burrows go three feet or so into the ground. Adam explained that petrels fly out to sea at dusk, foraging for food, returning home before dawn. They appear to use gullies and river valleys to fly from the sea to the mountains. It is thought that the Jamaican Petrel would feed far out at sea on crustaceans, shrimps and the like, which come to the surface at night.

Adam Brown explained that predators were—and remain—a threat. In Dominica as well as in Jamaica, the last sightings of petrels coincided with the introduction of mongoose onto the islands, which happened in Jamaica in 1872. However, Adam Brown revealed that the Black-capped Petrel (Pterodroma hasitata) was rediscovered in Dominica, through thermal imaging and radar, in 2015. Again, in January 2020 hundreds of birds were tracked, flying overhead. No nests have been found, but adult birds have been found on the ground, usually disoriented or injured.

On Hispaniola, where Adam Brown, EPIC and local partners at Grupo Jaragua have conducted a great deal of field work, Black-capped Petrels’ nests were found during an expedition in the hilly region of the Haiti-Dominican Republic border, in 2007. Mongoose, rats, and feral cats are always around, but the birds exist. So predators may not be the whole story. Over-hunting during the nineteenth century may also have been a factor in the birds’ decline.

So, where was the Jamaican Petrel last seen? Back in the nineteenth century, it was spotted in the slopes above Nanny Town and near Cinchona (the last known nest was found when the ground was being dug for the Cinchona Gardens, established in 1868) in the Blue and John Crow Mountains. These areas appear to be a good starting point for a search; it is possible that the birds would use the Rio Grande Valley in Portland as a flight path.

Adam Brown took his radar equipment up to the Cinchona area, and on March 22, 2016, he detected six petrel-like “targets” flying at approximately 65 km per hour, with two circling for a while before retreating out to sea (perhaps looking for future nesting sites). Could they have been Black-capped Petrels, or Jamaican Petrels? Petrels are known to be fast flyers, clocked at over 50 kilometers per hour on radar in Hispaniola.

Prior to Adam’s work, Dr. Douglas and a colleague, Herlitz Davis, had spotted a Black-capped Petrel off Jamaica’s south-east coast. Now Adam is interested in investigating the waters south east of Jamaica for this elusive bird.

The mystery of the Jamaican Petrel has not been solved—not by any means. However, there is hope. Nocturnal creatures can, of course, more easily escape notice. There may well be small colonies of the mystery bird, way up there in the Blue Mountains.

Dr. Susan Otuokon, Executive Director of the Jamaica Conservation Development Trust (JCDT), is firmly convinced that the Jamaican Petrel exists. She pointed out that the Jamaican Hutia (Coney), which is found in the Blue Mountains, and the Jamaican Iguana were once considered extinct; however, they were “rediscovered.” Dr. Otuokon added that the Blue and John Crow Mountains National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that the non-profit organization manages, is home to an extraordinary number of rare and endemic species of flora and fauna. Although JCDT is not a research institute, trained park rangers, tour and field guides are available to assist visiting scientists.

The webinar ended on a hopeful note. If you are up in the Blue and John Crow Mountains at night, and you hear an eerie cry in the valleys…

You never know. The lost Jamaican Petrel may be found again.

Searched in John Crow mountains in 1971 with David Wingate. No luck! Better luck to next generation!