A galaxy of shorebirds! Craig Watson of the USFWS shares stories from the field on Year Five of Piping Plover surveys in the Turks and Caicos Islands.

On Piping Plover Cay

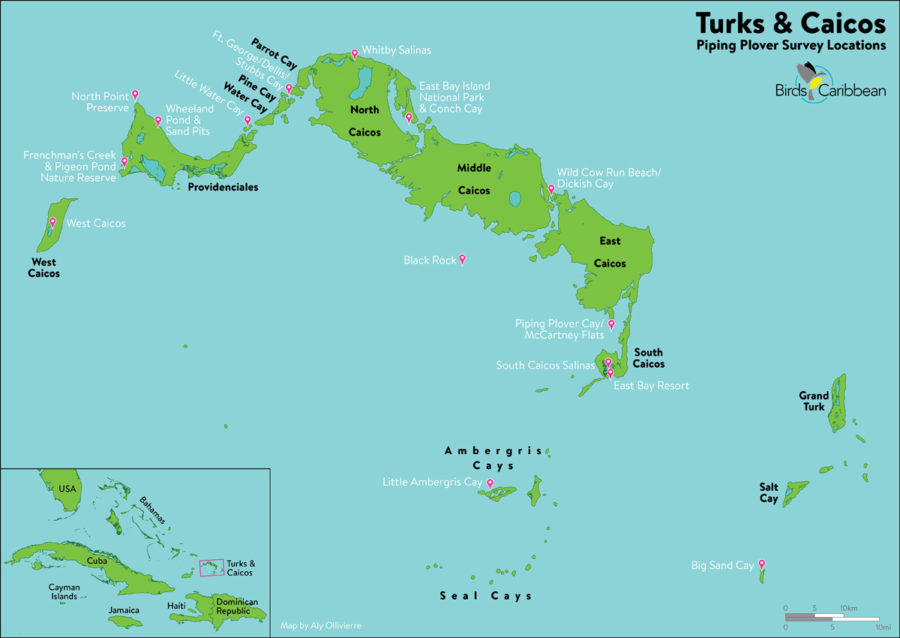

It was January 2020, and the Fish Fry festivities in Bight Park, Providenciales were in full swing as I arrived in Turks and Caicos, eagerly looking forward to a great couple of weeks of shorebird surveys in the islands. I soon discovered that my colleagues, now in their fifth season of surveys, had already experienced great success before I arrived. They recorded an astounding number of individual shorebirds on Black Rock—nearly 5,000, including over 2,800 Short-billed Dowitchers and 180 rufa Red Knot, a threatened species in the USA and Endangered in Canada.

We had named a small cay northeast of South Caicos “Piping Plover Cay,” and sure enough, 43 Piping Plovers had already showed up. This amazing little bird is also Endangered/Threatened in the US and Endangered in Canada. This spot, where our team observed a high count of 88 Piping Plovers in 2017, is not just the most important site in the Turks and Caicos, but an important winter site for the entire Atlantic Coast Population. Most Piping Plover winter sites have less than 10 birds, while the numbers of Piping Plover on this tiny island exceed the 1% threshold for the biogeographic population.

A Special Bird and a Recovering Island

The following day brought some thrilling discoveries. I set off to conduct surveys with Dodley Prosper of the Turks and Caicos Department of Environment and Coastal Resources (DECR) and to our delight we located 5 Piping Plovers on Stubbs Cay. One was really special; it had been banded in New Brunswick, Canada as a chick, returning to the same Canadian location in 2019 and 2020 to breed! Moreover, while Dodley and I were surveying the small islands between Providenciales and North Caicos, the rest of the team found 32 more Piping Plovers on Little Ambergris Cay, west of South Caicos. This was more than we had ever found there in our five years of surveying. After Hurricanes Irma (and Maria) hit hard in 2017, sucking away several sandy beaches, no plovers were seen. Thus, it was comforting to realize that not only the habitat, but also the numbers of this species appeared to be rebounding on this uninhabited wetland nature reserve. This was a very encouraging start to our fifth season!

How We Got Started

Our annual surveys in Turks and Caicos began in early 2016. We wanted to know how many Piping Plovers and other shorebirds wintered there, and how important this scattering of over forty coral islands was for their fragile populations. After the hurricanes of 2017, we also assessed the storms’ impact on the birds and the places they made home during the winter months. Surveys have also focused on identifying potential threats to winter habitats.

Unfortunately, there are a range of threats that are common to many parts of the Caribbean: sea level rise caused by climate change factors; invasive species; disturbance from recreational activities; and development. It was important for us to work with many local partners, including the TCI DECR, who now have first-hand information to continue monitoring and protecting the most critical habitats. Now, the question is: will the significant numbers of Piping Plover, Red Knot, and Short-billed Dowitcher we have discovered in the past four years continue to use the islands during the winter? And how will the severe storms affecting Caribbean islands more frequently influence the shorebirds’ population?

Will these shorebirds, especially the Piping Plover, survive these growing challenges?

Over the next ten days, our team explored much further. We revisited many areas we had been to in previous years, discovered new sites, and even used airboats for the first time in our surveys to access shallow sand and mud flats that were otherwise inaccessible. The weather was good, the beauty of the islands was remarkable, and with our new discoveries more information is now available to help conserve shorebirds in the islands.

Piping Plovers Making Moves

This winter our total Piping Plover count was slightly over 140. This was the second highest since our high count of 193 in 2017, and far higher than our low count of 62 following Irma and Maria in early 2018. At this point, we are not sure whether this reflects a true rebound from the storms or shifts in the use of habitats afterwards. We will need to conduct further surveys to be able to find the real answer, and to understand the meaning of the numbers that we observe annually. Piping Plovers form a strong attachment to their winter homes. Individual birds are known to use the same areas each winter, which may include sand flats, smaller cays, or multiple beaches.

Based on our previous knowledge of how the birds use specific areas, we were able to split into two teams to survey extensive habitat within a couple miles of where Piping Plovers had been observed in the past. This led to an exciting and fascinating discovery: Piping Plovers were moving back and forth between these areas during their daily activities, even within the same tide cycle. With the two teams observing at the same time, we were able to record band numbers from birds moving around these areas at two locations on separate days. Success! Now we were able to get a grasp of the birds’ local movements.

An Airboat Makes A Successful Debut

The large sandy flat area surrounding Piping Plover Cay on the northern end of South Caicos and McCartney Flats on the south side of East Caicos have several nearby sites used by a single flock of Piping Plovers. Although the distance between these two sites is relatively short (~1.25 km), making it easy for the birds to fly back and forth, it is a struggle for us humans to search—unless, of course, we have two teams and an airboat. Numbers on Piping Plover Cay had dropped dramatically since the hurricanes, but we were thrilled to find that over 50 Piping Plovers were using these two surrounding areas.

This was the first year we attempted to use an airboat to conduct surveys. The Beyond the Blue fishing guides out of South Caicos assisted us and we were able to reach several areas that we had never been able to access previously. We could never forget our first (and only) attempt at a survey in the past, when we dragged kayaks across what seemed like endless sand flats. This time, we were at first concerned about airboats disturbing birds so we proceeded with caution, stopping at a distance and then wading close-in by foot. The birds were hardly disturbed at all; and we would never have found them without the use of the airboat.

Birds, Not Conchs, on Conch Cay

Conch Cay, between Middle and North Caicos, and East Bay Island National Park, just off the northeast coast of North Caicos, are neighbouring sites used by Piping Plovers. Conch Cay and the sand flats at the southern tip of East Bay are pretty close together (~1.5 km) making it a short flight for plovers. Again, it had been difficult for just one team to observe the birds’ movements to and fro. This time, while one team was surveying Conch Cay, those birds flew directly to where the team on East Bay was surveying (up to 30 individuals had been observed here in the past).

We had never seen Piping Plovers on Conch Cay before—another new site to document! We realized that these birds may utilize neighboring small cays and beaches as one larger site. In other words, it is all part of the same neighbourhood for them.

Three cays northeast of Provo—Dellis, Stubbs, and Ft. George—also proved to be Piping Plover wintering sites. For the first time a small flock was observed on Stubbs Cay. These birds flew in the direction of Dellis Cay and were relocated later by observing the same bird with the same black flag marker on its leg! This means that not just one or two islands need protection for the continued survival of the Piping Plover. They are actually moving around much larger areas. So, these entire complexes of islands, cays, and intertidal flats need to come under the conservation umbrella.

Snowy Plovers, Salt Flats and Flags

New findings did not end with Piping Plovers this year. On the old sandstone dikes of the South Caicos Cemetery Salinas (salt flats) we counted 17 Snowy Plovers. The Salinas are precious habitats for shorebirds and in our years of surveys we had only detected one Snowy Plover at Northwest Point Preserve two years ago! The Salinas support 21 species of shorebirds and 16 species of waterbirds, including large numbers of migrating Stilt Sandpipers, Short-billed Dowitchers, and Least Sandpipers. The Snowy Plover is a relatively uncommon resident in the northeast Caribbean, and another subspecies listed as Threatened in the U.S. It is fantastic to know that Snowy Plovers are year-round residents here in the Salinas on Turks and Caicos!

And the Piping Plovers waved flags! Perhaps one of the highlights this year was that nineteen (19) of the Piping Plovers we observed were tagged with unique color flags and codes, identifying the individual bird and its breeding origin. These birds breed in Canada and the U.S. and all but one were banded on their breeding grounds—which included beaches in New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia. One bird was marked as a migrant moving through North Carolina. Other flagged species recorded in the islands were Red Knot, Ruddy Turnstone, and Sanderling. These resightings are critical, as they are telling us where we need to protect and manage the places where they stop and settle. This will help sustain them throughout their travels, whether they are breeding in Canada, migrating, or wintering in the Caribbean! Keep an eye out for marked shorebirds on your island, report sightings (BandedBirds.org) and contribute to improving our collective knowledge!

Checking out New Spots

Our teams ventured further afield, visiting and surveying areas that we had not looked at in past years. One such area was the island of West Caicos and nearby cays. We had a bit of a bumpy ride out to the cays, but all in a day’s work! We found that some of the smaller cays really did not have suitable habitat for Piping Plovers. West Caicos had some beach areas on the east shore similar to other beaches where Piping Plovers were found. However, most of these beaches were very high energy—not a suitable environment for roosting or foraging birds. We did find a good population of Bahama Mockingbird, which was previously undocumented. The team also found good numbers of seven species of shorebirds including Stilt Sandpiper, Short-billed Dowitcher, and Lesser Yellowlegs, all identified as critical species in the Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative.

For the first time we conducted comprehensive surveys in and around the Wheeland Ponds in Providenciales. It is an area of brackish ponds and mangroves, as well as old sand mining pits between Northwest Point and the Blue Hills area. Historically, the area was used for agriculture and sand mining, and for “wrecking”—the shipwreck salvage business. The salinity of the ponds along with the limestone outcroppings support the same types of wildlife, particularly birds, as in other areas. Our surveys detected approximately 20 species, 10 of which were shorebird species, with significant numbers of Black-necked Stilts, Killdeer, and Wilson’s and Black-bellied Plovers. Other birds of interest included American Flamingo, White-cheeked Pintail, and Least Grebe. Currently, the 96-acre area is being considered for inclusion in the Turks and Caicos national park system, as a critical habitat reserve.

Valuable Partnerships in Conservation

What would we do without our partners? The success of our surveys would not have been possible without this network of awesome people assisting in our efforts. The collaboration has grown over the last five years and now includes many local colleagues, most notably the TCI Department of Coastal and Environmental Resources (DECR). Although first led by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), in recent years surveys have been jointly led by USGS, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and DECR. From the start, the DECR has provided boats and personnel every year, and over time their members have developed significant expertise in surveying shorebirds. For the first time in 2020, DECR was in charge and worked independently on a survey of Big Sand Cay.

BirdsCaribbean, SWA Environmental (Kathleen Wood), the Turks and Caicos Reef Fund (Don Stark), and the Turks and Caicos National Trust (supported by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) are local organizations that provided funding support, in addition to the survey assistance by Kathleen Wood. Big Blue Collective (Mark Parish), Beyond the Blue (Bibo), and local guides Tim Hamilton and Cardinal Arthur provided invaluable knowledge of the islands, the marine landscape, and skills in navigating the turquoise waters. In many cases these boat operators went above and beyond our expectations. They got us where we needed to go when we needed to be there, working long hours for not much pay.

Information sharing is what it’s all about. During our five years of surveys, we have observed approximately 80 bird species and roughly 13,000 individual shorebirds, providing DECR and local partners with the “know how” to assist in managing the natural resources of the islands. Data on Piping Plovers and other shorebird hotspots has been used by the TCI Government to inform all-important environmental impact assessments and other land management decisions.

It is likely the current pandemic may not allow international partners like myself to conduct another survey in 2021. However, we all hope that another year of surveys can be completed by our many great partners on the ground in Turks and Caicos. The islands are a true treasure for shorebirds and we need to protect and manage these precious places for the continued survival of the species and the environment.

Each year has brought new discoveries and the more we discover, the more effective our partnerships and conservation efforts become! The charming Piping Plover, a very special winter resident in TCI and Bahamas, remains an inspiration to us all.

Craig Watson is the South Atlantic Coordinator of the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture. His job is to coordinate bird habitat conservation efforts with partners for high priority species that utilize the Atlantic Flyway (Canada to South America). If you would like to help fund future surveys and conservation actions for Piping Plovers and shorebirds in the TCI, Bahamas and the region, please click here.

Enjoy the photo gallery below. Hover over each photo to see the caption; click on the first photo to see a slide show.