What is a Gavilán? Have you seen a Guaraguaíto?

These are two names sometimes given to the elegant Ridgway’s Hawk, a Critically Endangered bird of prey which lives only on the island of Hispaniola. This hawk has an estimated population of just 450 individuals in the Dominican Republic, and is believed to be extirpated in Haiti. Since 2000, The Peregrine Fund – a non-profit organization working for the conservation of threatened and endangered birds of prey worldwide – has been in the Dominican Republic, fighting to save this species. The program consists of four major components: scientific research and monitoring, assisted dispersal, environmental education and community development.

I came on board this project in 2011 and have been amazed at the incredible strides our great team has made for the conservation of this species. As I write this, we are right in the middle of the busiest time of year – Ridgway’s Hawk nesting season! As many of our local field crew are busy nest monitoring, banding chicks and treating young for botfly infestations, I have had the privilege to spend some time at our new release site in Aniana Vargas National Park.

The Community is Key

Part of our long-term goals for the conservation of this species include creating 3 additional populations outside of Los Haitises National Park – the location of the last known population of this species. Last year, our team leader, Thomas Hayes, spent a lot of time searching for potential new release sites that would provide the hawks with sufficient prey and nesting habitat as well as relative protection from human threats. In fact, one of the main reasons we chose this park was because of the communities that surround it. Most of them make their living selling organic cacao and are already committed to environmental protection!

But before we could begin releases in this area, we had to do much more than pick a spot and set up a release site. We had to make sure we had the support from the local community members. After all, the success of the project and the survival of the hawks very much depends on the residents’ reactions to these efforts.

So, over the past several months our team has made many visits to Los Brazos, the nearest community to the release site. We held town meetings to discuss the possibility of releasing hawks in the area. We also brought a few individuals from the town of Los Limones (outside of Los Haitises National Park) where we have been working for close to two decades. The residents learned from them first-hand what benefits the project could bring to their own community. After receiving the go-ahead and full support of the people of Los Brazos, in March we constructed two towers to house the young hawks prior to release. We hired several community members to help with transporting materials through the forest to the site (about a 30-minute walk) and construction.

How Are the New Releases Doing?

As of the writing of this report, 14 Ridgway’s Hawks have been released into the park. They continue to do well. Nine more are currently in the hack boxes* and will be released within the next two weeks. We hope to bring at least two more hawks to the site, to be able to release a total of 25 individuals this year. All the hawks have been fitted with transmitters which help us locate them during this critical stage of their development.

In order to benefit the community as well as the hawks, we built and provided one free chicken coop to each household in Los Brazos. This will help prevent any conflicts between Ridgway’s Hawks, other raptors and domestic fowl. We also hired and are in the process of training three full-time, seasonal employees and three seasonal, paid volunteers. These young community members are responsible for monitoring and caring for the released hawks, under the supervision of Julio and Sete Gañan. Some have even taken the initiative to give presentations in nearby communities and schools. Our presence in Los Brazos also provides other sources of income for individuals as we pay for additional services such as cooking, laundry, house rental and transportation, among others. We have been overjoyed by the enthusiasm shown by the people of Los Brazos and surrounding communities in support of this project and the Ridgway’s Hawk.

Over the next few months, the released hawks will naturally develop their hunting and survival skills and in no time – they will become completely independent. When that happens, the young hawks will disperse to other areas within and outside the park.

Learning More About the Guaraguaíto

In order to keep the hawks as protected as possible once this happens, we have to make sure our education program reaches other surrounding communities before the hawks do. To that end, we expanded our education program to the region. To date we have visited 10 other communities that surround the park, going door-to-door, and giving presentations in local schools. We have also engaged local teachers to help us spread this important conservation message.

To date, we have conducted two workshops for a total of 38 teachers working in schools around Aniana Vargas National Park. These two-day workshops are designed to provide teachers with the tools necessary to be able to talk about conservation issues one-on-one within their communities and in the classroom. The training also showed how to utilize whatever materials are on hand to create fun and dynamic learning experiences for their students. Our goal is for the educators to duplicate what they learned and help spread the word about the hawk and conservation far and wide.

Workshop activities include creating artistic sculptures of Ridgway’s Hawks out of recyclable materials; putting on a play – complete with actors, costumes and scenery; a bird watching excursion; playing a food-chain game; and participating in “Raptor Olympics.” During these exercises, the teachers are learning about the Ridgway’s Hawk’s biology, food chains, birds of prey, and conservation issues and actions. We have since received word from some participants, who are already putting what they learned into action. Some teachers have begun giving presentations at their schools about the hawks, and one hosted a mini-workshop with the other teachers at her school. We have also conducted art activities in several schools around the area, focused on birds of prey and the Ridgway’s Hawk.

The Future Looks Brighter, Thanks to Support!

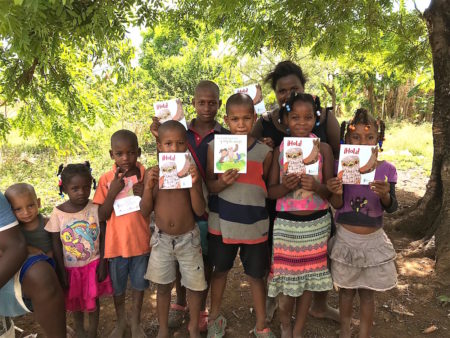

Additionally, we have printed our first children’s brochure (in Spanish and Haitian Creole) and poster, and we are making progress on several other educational materials! We still have a lot of work to do in order to conserve this species and to reduce the human threat to its survival. However, we have made great strides and will continue to work hard for a better future for this beautiful raptor and for all wildlife and wild places, besides the human communities in Dominican Republic that live alongside them. I can’t wait!

We are grateful to our in-country partners Fundación Grupo Puntacana, Fundación Propagas, ZooDom, Cooperativa Vega Real, and Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: and to our generous donors: BirdsCaribbean and the Betty Petersen Conservation Fund, and Premios Brugal Cree en Su Gente. And very importantly, we thank all of our local employees and volunteers, and all the community members for ensuring the success of this project. We could not do it without your support!

Hover over each photo to see the caption or click on the photo to see a slide show.

By Marta Curti, The Peregrine Fund. Marta Curti began working as a field biologist with The Peregrine Fund (TPF) in 2000 when she worked as a hack site attendant on the Aplomado Falcon project in southern Texas. She has since worked as a biologist and environmental educator on several TPF projects from California Condors in Arizona to Harpy Eagles and Orange-breasted Falcons in Belize and Panama. She has been working with the Ridgway’s Hawk Project since 2011.

* A hack box is a specially designed aviary that serves as a temporary nest for young hawks awaiting release into a new area. The hawks are places in the hack box at a young age (before they are naturally able to fly). They remain in the hack box for about 7-10 days, until they are at the age of fledging. During their time in the hack box they are fed daily and become accustomed to their new home so that when the doors are open, they will naturally want to return to the site for food. Over time they will develop their hunting skills and once independent they will disperse naturally from the release area and no longer show up for the food we provision.