The last time we met them, Yvan Satgé and his colleagues from Grupo Jaragua and USGS – South Carolina Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit were hiking up and down the high slopes of Loma del Toro, in the Dominican Republic. They were in search of active Black-capped Petrel burrows in which to set traps for adults returning to feed their chick. Read Part I of the story here.

“Hay uno!” – There is one!

Excited by the prospect of capturing Black-capped Petrels for the first time, I am awake well before sunrise. Even the local rooster is surprised by the beam of my headlamp emerging from the tent. I knock on the door of the caseta where the rest of the team sleeps and, within a few minutes, our group heads into the forest, a flock of LED lights floating in the night mist. When we reach the ridge that marks the edge of the petrel colony, there is just enough light to sense the tall presence of Hispaniolan pines, their bark beaded with water droplets caught in lichen and moss. We catch our breath while listening to the muted sounds of dawn: a few birds warming up in the distance, insects starting to chirp in the bushes, and Pirrín…who never stops talking.

To avoid unnecessary disturbance, we decide that only Ivan, the youngest and fittest of the group, will check on the traps. If he finds a trapped petrel, he will call us by radio to join him. Ivan scrambles down the slope of loose soil and rocks and disappears into the dense understory vegetation. Up on the ridge, as we solemnly listen to the radio, even Pirrín is quiet. In the momentary silence, I review the steps in the tagging process myself: record the time; remove the bird from the trap; check it over for condition or injury; place it in the cloth bag; weigh it; attach a metal band to its right leg. If the petrel is heavy enough, glue the GPS tracker to the base of the tail feathers with epoxy, and secure it with strips of waterproof cloth tape and a small zip-tie. Take measurements: tarsus, wing cord, bill (culmen) length and depth; take a picture of the bird’s profile; place it back in the nest; record the time. Collect any poop samples. Breathe.

The radio screeches: “Hay uno!” – There is one. My heart races as we enter the ravine, single-file. Despite our excitement, we need to move slowly through the branches and vines that block our path at knee and chest height. In front of the burrow, we review the procedure once again and assign roles. Ivan removes the trap from the tunnel’s entrance, revealing a small but handsome black and white bird with a black mask over its eyes and a shiny thick black beak: Diablotín, the Black-capped Petrel. Patrick places the petrel into the cloth bag and weighs it as José Luis takes notes. Meanwhile I begin to prepare the GPS tracking equipment, but Patrick stops me halfway through: “370g: it’s a light bird…” I won’t need the tracking equipment this morning after all.

The Seabird Biologist Receives Two Gifts from the Diablotin

An implicit standard in the tracking of birds’ movements is to keep the mass of the tracking equipment below 3% of the mass of the bird to avoid undue burden. Counting the waterproofing, epoxy, tape and zip-tie, the mass of our GPS loggers adds up to a bit less than 9g, meaning we could equip petrels weighing as little as 300g. The night before, however, we had decided to raise the weight limit in case the stress of tagging a smaller petrel might cause it to abandon its chick. As important as our research can be for the conservation of Black-capped Petrels, we do not want to jeopardize the health or reproductive success of the already-endangered birds we study. It is tempting to bend our own rule in our excitement – but it’s always best, in any expedition, to follow decisions made with a clear head.

The petrel rewards us with a gift of sorts: a fresh fecal sample for my diet study lands on my legs. Will this poop contain DNA from squid, or from some unknown prey? We hope to find out soon. Now, we band the petrel and, after quick measurements and a photo, it’s time to place it back in its burrow. Too happy to release my first Black-capped petrel, I am not careful enough of its beak and receive the mark of the seabird biologist: a bleeding gash into the flesh of my finger.

Over the next ten days, we capture eleven more Black-capped petrels, nine of which we equip with a GPS tracker. We also set up three “base-stations” near their burrows: powered by solar panels, the base-stations will download the data stored in a tracker whenever a petrel comes back to feed its chick. Ernst and his team will retrieve the base-stations and data when they come back in June for their monthly check of the colony.

A Patient Ball of Fluff

During our discussions, while, bathing in the sun after afternoon rains, huddled around the cooking fire, or preparing GPS trackers in the caseta at night, I have realized that spending so much time at Loma del Toro is challenging for the team. My companions have families and other responsibilities in town (Ivan will leave early to take tests for his high school certificate – we all thought he was finished with school for the year!). Although cellphones and WhatsApp make it easier for José Luis to chat with his wife and young kids or for Ernst to keep working on a multitude of other projects, their monthly monitoring visits to the colony usually last only a few days. Hence, we use these two weeks on the mountain as fully as possible.

One afternoon, Patrick, an expert rock-climber, refreshes the team’s climbing skills with two duffel bags full of safety equipment donated by Ted Simons, the leader of a 2001 expedition to locate Black-capped Petrel nests in this area. We use the ropes, harnesses and helmets to practice rappelling down petrel escarpments and climbing up trees where Hispaniola Amazons, a vulnerable endemic parrot also monitored by Grupo Jaragua, build their nests.

On other days, we search for petrel burrows. After many hours of bushwhacking in dense underbrush, we find two new burrows near the monitoring area. One of them houses a grey ball of down feathers: a 2-week old Black-capped Petrel chick patiently waiting for its parents to bring it food. The other nest contains only a cold egg. This is the fifth abandoned egg that we have found in the area; in the 8 years that Grupo Jaragua has been monitoring the species, Ernst has only found a few such cases. The reason for these abandonments is difficult to pinpoint, but may include the presence of feral cats (which can kill or disturb incubating adult petrels) or the lack of available prey in the petrels’ foraging areas (which means the parents must spend more time searching for food and less time incubating their egg). We hope that our research will help us better understand how these threats affect the petrel population. I collect the egg for the Dominican Museum of Natural History while Gerson builds a new roof of branches, rocks and soil to protect the petrel chick.

The First Annual Diablotin Festival Takes Off In the Rain

When doing fieldwork, it is easy to lose track of the “normal” world and to forget which day it is. During this expedition, though, there is an important date on our calendar: April 19th, the day of the first annual Diablotin Festival organized by our colleagues Anderson Jean (Société Ecologique d’Haïti) and Adam Brown (Environmental Protection in the Caribbean). That day, we put on our best field clothes, clean our muddy shoes, pack some supplies for the hike and for our friends, and head down the mountain into Haiti.

We enter the village of Boucan Chat, where students from two local schools line both sides of the road, wearing bird masks or tree costumes over their school uniforms. The students have spent weeks learning about Black-capped Petrels and the importance of protecting their habitat in the surrounding mountains. Protecting habitats benefits not only the birds but also the whole forest. Preserved from illegal logging, forests can store more water during the rainy season, preventing farmed fields from flooding and keeping natural springs flowing during the dry season.

The buzz of a drone raises a few heads amongst the children but most of them seem accustomed to its presence. After three years of on-and-off filming in the area, the “Save the Devil” filming crew has almost finished its documentary on Black-capped Petrel conservation in Boucan Chat. The next day, they will screen a short version of the film in front of the Boucan Chat villagers, who will ask to see the film three times in a row!

A band arrives on a convoy of motorcycles, and the parade begins. Villagers hurry to the roadside to watch and the puzzled looks quickly give way to smiles. The parade doubles in size before reaching the football pitch in the center of the village, surrounded by vegetable fields and a few majestic Hispaniola pine trees, a reminder of the forests that once covered these foothills. The local Diablotins team, sponsored by Black-capped Petrel conservation work as a way to raise awareness and pride for the species, wear new uniforms emblazoned with an image of the petrel. A female team is now also supported to provide gender balance.

The dark clouds that have enveloped the mountains in mist since morning soon burst into torrential downpour. The audience runs for shelter under crowded house awnings while the dedicated players run and slide in the mud, keeping their eyes on the ball despite the violent rain. The game ends amid shouts of joy, with a victory for the Diablotins: the spirit of the tough little seabird may have given them an advantage. After soaked, shivering goodbyes and an hour-long hike in the rain, we are delighted to find that the heater of our pickup truck is working. While we drive back to the top of the mountain, however, we can’t help thinking of the football players who, after a passionate game in torrential rain, returned to cold, damp houses with only the pride in their communities to keep them warm.

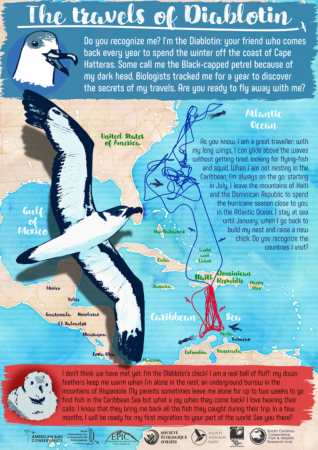

Back at the caseta, we huddle around the cooking fire to enjoy the pot of soup that Ivan has prepared. The clouds have lifted and we can see the first stars between the crowns of the Hispaniolan pines. Soon, a Black-capped Petrel wearing a small GPS will swoop down into the forest and hurry into its burrow. When it comes out again and flies away for another fishing trip, invisible radio waves will have transported the secrets of its travels to our base-stations, patiently waiting for Ernst and his team to return to the mountain.

Next time, in Yvan’s last blog post, we will learn about the travels of the GPS-tagged Black-capped Petrels and of the fish they catch, from Colombia to the United States.

Yvan Satgé is a Research Associate in the Lab of Dr. Pat Jodice, at the South Carolina Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit, Clemson University (Email: ysatge@clemson.edu). He has been studying various aspects of seabird ecology for the last few years.

Great article! What a dedicated team you have!

I have a question about cold eggs being treated as ‘abandoned’ and so removed. My limited experience with petrels and shearwaters suggests that an egg is not necessarily abandoned if it is cold. Petrel eggs are adapted to periods of short-term ‘abandonment’ and do not necessarily need to be incubated continuously. We frequently find a cold egg in Leach’s storm-petrel nests, that go on to raise a chick successfully.

No doubt you know this and take it into account – I hope so.