Hannah Madden, an ecologist with the Caribbean Netherlands Science Institute, provides an update on the status of the Bridled Quail-Dove one year after the tiny island of St. Eustatius was ravaged by Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Surveys just after the storms indicated the population was smaller, but similar to pre-hurricane levels. However, the extensive vegetation loss combined with an upcoming dry season and invasive predators meant that the battle for survival for this West Indian endemic had just begun.

Eight months after hurricanes Irma and Maria passed through the Caribbean, many aspects of daily life have returned to normal or have reached a new balance. While the dramatic effects of the storms are no longer international news, in some cases their consequences remain just as severe or are only just now revealing their impact. The population trend of the Bridled Quail-Dove on St. Eustatius (also knows as “Statia”) is one example of the latent and long-lasting effects of major climatic events.

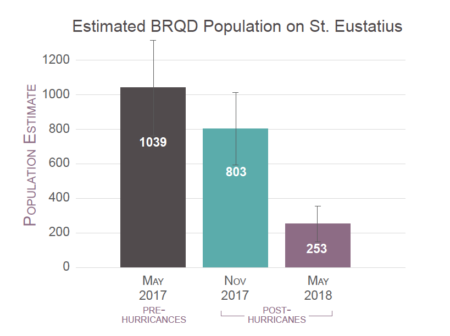

Our team conducted population assessments for this shy ground-dwelling species before the hurricanes in May 2017 and two months after in November 2017. At that time, there was no reason to be alarmed. Our most recent assessment this year in May 2018, eight months after the storms devastated the island, yielded extremely low population estimates. The results were disheartening.

Bridled Quail-Dove Biology

The Bridled Quail-Dove (Geotrygon mystacea) is a regionally endemic species in the family Columbidae. On Statia, they only found in upper elevations (above ~150m) of the Quill, a dormant volcano, and inside the crater. It is easily distinguished from other dove species by the turquoise patch on its neck and white stripe (bridle) under the eye. Observant hikers are likely to spot this bird wandering the forest floor during daylight hours in search of food (seeds, fruits and the occasional gecko or snail).

This species is extremely sensitive to weather conditions. Activity and breeding are very much dependent on rainfall, and the dove is vulnerable to hurricanes and extended periods of drought. Similar to other Columbids, the Bridled Quail-Dove lays clutches of two eggs in a flimsy nest made of twigs up to six meters above the forest floor. They do not fare well in areas of human activity. Numbers have declined across the species’ range, presumably due to habitat loss. Hunting and predation by invasive mammals such as the black rat (Rattus rattus) are also perennial problems.

Statia’s Forests Hard Hit by Hurricanes

Irma and Maria were the first recorded category five hurricanes to hit the Windward Islands. While Statia was spared extensive infrastructural damage in urban areas, its forest ecosystems did not fare so well. A recent publication by Eppinga and Pucko (2018) notes that an average of 93% of tree stems on Statia and Saba lost their leaves; 83% lost primary/secondary branches; 36% suffered substantial structural stem damage; and an average of 18% of trees died (mortality was almost twice as high on Statia than on the nearby island of Saba).

Our pre-hurricane assessment in May 2017 was encouraging. We found an estimated 1,030 (min. 561- max. 1,621) quail-doves across their local habitat, possibly the highest known density in the region. We were pleased and felt safe in the knowledge that the doves enjoyed some level of protection in the Quill National Park, which is also a designated Important Bird Area.

Following the hurricanes in November, however, we repeated the surveys and recorded a decrease in the population of around 22% to 803 (min. 451 – max. 1,229). Moreover, we were worried about a continuing decline in the population, as a direct result of the hurricanes. Also, since rat populations are known to spike dramatically following hurricanes, we feared that this problem might worsen.

We conducted surveys again in May 2018, hoping to coincide with the quail-dove’s peak breeding season. However, instead of the usual ~70 transects, we had to walk an exhausting 255 transects in order to find enough doves for analysis. No doves were heard calling, most likely as a result of delayed breeding, and only 32 were detected during 2018 surveys compared with ~92 in previous years. Our fears were realized when we ran the analysis: in May 2018, the Bridled Quail-Dove population had declined by 76% compared with the previous year. It is currently very small at around 253 individuals (min. 83 – max.486).

Will the Bridled Quail-Dove Disappear from Statia?

With such a small population, there is a very real risk that Bridled Quail-Doves could become extirpated on St. Eustatius. Conservation efforts are now urgently required. We do not know a great deal about the Bridled Quail-dove’s survival and reproduction rates. However, black rats live in all vegetation types within the dove’s entire range. It is critical that we control these invasive mammalian predators, as a first step towards boosting the species’ breeding levels and survival rates, in order to bring back the population of this highly vulnerable species to pre-hurricane levels.

Thanks to funding by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs under their Nature Fund initiative, a rodent control project, facilitated through the Caribbean Netherlands Science Institute (CNSI), is running on St. Eustatius. The authors are grateful to St. Eustatius National Parks Foundation for granting permission to conduct surveys in the Quill National Park. We also wish to thank the many generous donors who contributed to BirdsCaribbean’s post-hurricane fundraising appeal, which covered Dr. Frank Rivera’s costs to conduct surveys in November 2017.

By Hannah Madden (CNSI), Frank Rivera-Milan (USFWS) and Kevin Verdel (Utrecht University). Hannah is a Terrestrial Ecologist in St. Eustatius with the Caribbean Netherlands Science Institute. She also works as a bird and nature guide in her spare time, sharing the beauty and diversity of Statia with visitors. Hannah is an active member of BirdsCaribbean and has participated in several training workshops and conferences. She has published papers on different taxonomic groups, but especially enjoys working on birds.

Thank you for the important report. What is your confidence level in your ability to detect the doves when they were not calling? You obviously made extensive survey work. Assuming that your surveys were accurate – locating only 33% of the previous numbers – did you find any evidence that would help you to determine the reasons for the increased mortality? It would seem unlikely that the doves were directly from the hurricane. The seeds that they feed on probably would still be available despite the hurricane. Thus the rat hypothesis is plausible. Did you find increased populations of rats? I know that there is some evidence of rats killing adult doves, but it would seem that the impact of predation would be greater on eggs, nestlings and recent fledglings. It seems that the doves may not have bred since the hurricane.

The local abundance of the BRQD on the slopes of the volcano are consistent with what I found with Grenada Doves. Although critically endangered, they are locally abundant along one wooded slope in what is now Mt. Hartman national park.

The Grenada Dove population may have recovered *(to its previously very low levels) following the Hurricane Ivan that devastated Grenada in 2004. However mongoose populations are unbelievably high so the recovery has not been complete. If you have not done so I suggest that you be in touch with Bonnie Rusk who is studying the Grenada Dove. there may be lessons from Grenada that would be useful to you.

keep up the important work!

Thanks, David, for your questions, comments and suggestions. I will pass them on to Hannan Madden to get her reply. Frank Rivera helped Hannah design the surveys and with some of the field work so I know they were conscious of detectability issues. We are also in touch with Bonnie and work with her on Grenada Dove conservation. I believe they are still trapping mongoose. I will check in with her as well. Warmest best, Lisa