Say “Dominican Republic” and almost instantly the image that appears in one’s head is that of a long, straight and blinding white-sand beach on which an infinite stream of foamy crests come to end their journey across the blue-green Caribbean canvas. This mental picture has been implanted in our brains by thousands of magazine articles and television ads, and though beautiful, there is nothing particularly unique about it.

The setting of the most recent Caribbean Birding Trail Interpretive Guide Training in the Dominican Republic was the virtual opposite of this cookie cutter image of a sandy beach. This time the training was high up in the mountains—a scene like no other on the planet—in a valley surrounded by high ridges everywhere, and all around a tapestry of produce fields that extend as far as the eye can see. Rows of carrots, lettuce, potatoes, and strawberries carefully divide the land into small and big parcels. The air is chilled by the mountain breeze, enough to make us don our jackets and blow warm air into our cold hands. This, too, is the Dominican Republic, or La Española as the first Spaniards named it the last days of the 15th Century when they first arrived in these realms:

The land there is elevated, with many mountains and peaks incomparably higher than in the center isle. They are most beautiful, of a thousand varied forms, accessible, and full of trees of endless varieties, so high that they seem to touch the sky, and I have been told that they never lose their foliage. I saw them as green and lovely as trees are in Spain in the month of May. Some of them were covered with blossoms, some with fruit, and some in other conditions, according to their kind. The nightingale and other small birds of a thousand kinds were singing in the month of November when I was there.

After reading this paragraph from a letter sent by Christopher Columbus to Luis De Santangel in which he announced the discovery of new land, we are convinced that Columbus did in fact visit the area of Constanza and Valle Nuevo, or at least he visited a very similar mountain area not far from here, because this is exactly the feeling we had when we arrived for the third Caribbean Birding Trail Interpretive Guide Training program.

The training took place at the AltoCerro Hotel in Constanza, from Oct 19 to 23. During the workshop we visited several birding hotspots such as Ebano Verde and Valle Nuevo National Park. The valleys and high plateaus of the “Cordillera Central” (Central Range) of Hispaniola are home to a very distinctive array of birds, from dozens of migratory warblers to the Ciguita Constanzera, better known as Rufous-collared Sparrow, a common bird in mainland Central and South America, but mysteriously found in an isolated population the heart of the Dominican Republic. A total of 54 species of birds were spotted throughout the week, including 11 of Hispaniola’s 29 endemic bird species.

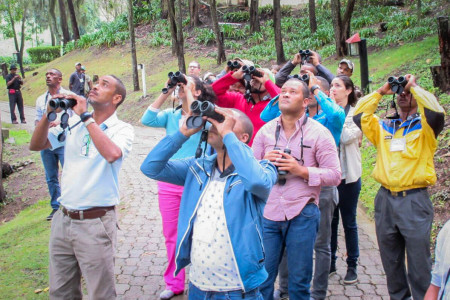

Twenty-three Dominican and one Haitian student learned how to identify and show the birds of their island. They came from all over the island and from different backgrounds that included tour guides, environmental educators, hotel managers and park rangers. The five-day training covered 3 main aspects:

- Bird identification and being a bird guide

- Environmental interpretation

- The conservation imperative of birds and their habitat

Facilitating the training were Beny Wilson and Rick Morales, professional guides and certified Interpretive Trainers from Panama; Andrea Thomen, Caribbean Birding Trail (CBT) Local Coordinator from Dominican Republic, and Holly Robertson, Project Manager of the CBT. Kate Wallace, long-time birding guide on the island and co-author of “Ruta Barrancoli: A Bird-finding Guide to the Dominican Republic,” also assisted and was an invaluable resource for all the participants and trainers as well as a strong voice for the conservation of the birds.

Many of the students who had never before looked at a bird through a pair of binoculars expressed their feeling of new discovery and empowerment, for now they had the tools to go out and search for birds in the wild. They also learned how to make meaningful connections about the birds and their environment for future visitors to this part of the world.

The Caribbean Birding Trail is an initiative that seeks to connect the natural and cultural heritage of the Caribbean islands through the training of local naturalist guides who will then be able to identify and interpret the birds and their habitats for local and foreign visitors. The CBT is being developed to raise global awareness of the unique birds and biodiversity of the Caribbean and to create a sustainable economy around these rare species, in an effort to protect them.

Understandably Columbus did not give any deeper consideration to the birds. He was in search of more immediate and tangible outcomes. But today, birds and humanity’s attitude towards them are exactly the reasons for us to be here. Today, we know much more about the birds in the Caribbean. We understand that it is important to safeguard their future because in many ways it is our future too. If forests and other natural habitats disappear, so to do the life-supporting services they provide, threatening our survival and well-being.

Our ultimate goal is that birds become a common thread for visitors of these natural regions of the Caribbean. The fantastic diversity of birds found in the region, over 170 endemics as well as many residents and migrants, mirrors the diversity of landscapes, peoples, languages, customs, and environmental challenges of these countries, and so naturally we believe that birds are an unparalleled gateway into this most unique and fascinating region of the world.

The CBT Interpretive Guide Training was made possible through the generous support of our sponsors and local partners. These include: the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of the Dominican Republic, Ministry of Tourism, Fundación Propagas, AltoCerro Hotel, SOH Conservation, Villa Pajon Eco-lodge, Fundación Jose Delio Guzmán, Tody Tours, The National Aviary, Grupo Acción Ecológica, BIC, Grupo Jaragua, Fundación Moscoso Puello, Puntacana Fundación Ecológica, Fundación Progressio, Vortex Optics, The Marshall Reynolds Foundation, and Rufford.